AKA

Behavioral Theory

Conditioning Theory

Science of Behaviour

Focus

Associations between identifiable environmental stimuli and observable measurable behaviorsPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … repertoire of behaviors

- Knowing is … behaving (triggered by stimuli)

- Learner is … an organism

- Learning is … changes in behavior (linking stimuli to responses)

- Teaching is … training; engineering behavior (through deliberate conditioning)

Originated

late-1800sSynopsis

Behaviorisms reject the notion that knowledge is some sort of external, stable, and context-free object that exists independently of knowers, and they redefine personal knowledge as established and stable repertoires of behavior that are triggered by events in the world. In this frame, learning has a specific and narrow definition:- Behaviorist Learning – a change in behavior that can be attributed to experience

- Behavioral Plasticity – the extent to which one’s behavior can be affected or changed by experience

- Black Box – a general term to refer to any situation in which observable inputs lead to observable outputs through non-observable processes. The phrase was routinely used to describe and explain the foci and methods of Behaviorisms, and thus to justify its deliberate ignorance of mind and cognition. That is, the human mind was seen as a Black Box, from which it followed that speculating on its content (i.e., cognition) was without scientific merit.

- Equipotentiality – the unproven assumption, common to most Behaviorisms, that there are laws of learning that do not vary across stimuli, responses, and reinforcements. (Note: should not be confused with Equipotentiality described under Neuroplasticity.)

- Behavior Theory (General Behavior Theory) – any theory that embraces the assumption stimuli- and response-based principles are sufficient to explain the learning and maintenance of behavior

- Centralism (Centralist Psychology) – the conviction, prevalent among some researchers of Behaviorisms, that behavior is a function of the central nervous system (Contrast: Peripheralism, below.)

- Peripheralism (Peripheralistic Psychology) – an attitude, prevalent among some researchers of Behaviorisms, of ignoring the brain (and the rest of the central nervous system) and focusing on peripheral body parts (i.e., those that can be observed in action). (Contrast: Centralism, above.)

- Involuntary Response – a response/behavior that is not under one’s conscious control (e.g., salivating when hungry and presented with food)

- Voluntary Response – a response/behavior that is under one’s conscious control

- Factor Theory of Learning – an umbrella category that includes any theory of learning that rejects monistic theories of learning. Examples include:

- Two-Factor Theory of Learning (Hobart Mower, 1940s) – the perspective that Classical Conditioning and Operant Conditioning are distinct forms of learning and that neither is reducible to the other

- Acquired Response (Learned Response) – among Behaviorisms, a response that is due to an event of learning. (Note the affiliation with the Acquisition Metaphor, which appears to have been carried over from Folk Theories.)

- Conditioning – the model of teaching most strongly associated with Behaviorisms. Within those discourses, Conditioning is the process or event of influencing behavior.

- Stimulus–Response Association (Stimulus–Response Association; S-R Bond) – strictly speaking, an association between a trigger (Stimulus) and a behavior (Response)

- S–S Learning (Stimulus–Stimulus Learning; Stimulus Substitution Theory) – when one stimulus comes to stand in for another (e.g., a bell standing in for food) in triggering a nonvoluntary behavior (e.g., salivation) (see Classical Conditioning)

- S–R Learning (Stimulus–Response Learning) – the creation or bolstering of a Stimulus–Response Association (see Operant Conditioning)

- S–R–O Learning (Stimulus–Response–Outcome Learning) – the hypothesis that an Outcome (of reinforcement or punishment) is always a consequential aspect of S–R Learning (see above)

- S–O Association – the association between a trigger (Stimulus) and a reward or punishment (Outcome)

- S–(R–O) Model (Stimulus–(Response–Outcome) Model) – the hypothesis that, once an S–O Association has been established, the trigger (Stimulus) activates an association between the conditioned behavior (Response) and reward or punishments (Outcome)

- S–R Psychology (Stimulus–Response Psychology) – an approach to Psychology focused on behavior, which is conceptualized in terms of stimulus and response. Prominent theories in S–R Psychology include Thorndike’s Connectionism (of Behaviorisms) and Guthrie’s Contiguity Theory.

- S–O–R Psychology (Stimulus–Organism–Response Psychology) (Robert Woodworth, 1930s) – an elaboration of S–R Psychology that incorporates the suggestion that there are organism-based factors that contribute to behavior

- S–S Psychology (Stimulus–Stimulus Learning Model) – any learning theory that focuses on the formation of associations among stimuli. The range of such theories is broad – spanning, for example, Classical Conditioning (in which associations between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli are the focus) and theories with a fundamentally cognitive focus, such as Gestaltism.

- Behavioral Cusp (Sidney Bijou, 1990s) – a specific type of behavioral change that affords access to new and markedly broader possibilities – including new stimuli, new situations, new reinforcers, and/or new behaviors. The notion interrupts assumptions that are common to most Behaviorisms, such as the linear learning progressions and gradual accumulations of new behaviors associated with Chaining (see below).

- Chaining (Sequential Learning)– breaking down a skill or competency into elemental parts, and then using those elements to define a teaching/training sequencing. Chaining is usually associated with Behaviorisms, but it is also taken up by Instructivism and similar discourses. In the context of Behaviorisms, it refers specifically to a sequence of behaviors in which the outcome of one behavior becomes the stimulus for the next. Associated discourses and constructs include:

- Associative-Chain Theory (Associative Chaining Theory) (H. Ebbinghaus, 1880s) – a theory to explain the learning of complex behaviors, such as speech, based on Chaining (see below)

- Response Chain (S–R Chain; Stimulus–Response Chain) – a sequence of responses, each of which triggers the next. Using the symbols of S–R Psychology (see above), a Response Chain might be expressed as S1→R1→S2→R2→…→Sn→Rn.

- Cognitive Behavior Theory (Cognitive Behaviorism) – an umbrella notion that applies to any perspective that, contrary to Descriptive Behaviorism (see above), considers mental processes as important mediators of behavior and behavior change

- Configural Learning – learning to respond to specific combinations of two or more stimuli

- Descriptive Behaviorism (B.F. Skinner, 1930s) – both an umbrella category and an admonition, reflecting Skinner’s conviction that psychology should constrain itself to the observation and description of behaviors (i.e., religiously avoiding inferences to mental processes)

- Epiphenomenalism (Conscious Automatism) (James Ward, 1900s) – the suggestion that conscious thoughts and other mental events are by-products of physical events that have no causal influence on physical events, in a manner analogous to the steam released by a locomotive.

- Neobehaviorism (various, 1940s) – More an amplification of a defining impulse that a shift or revision, Neobehaviorism emerged as a school of thought founded on an uncompromising commitment to Positivism and its narrow band of deemed-to-be rigorous research methods. Prominent neobehaviorists included B.F. Skinner and Edward Tolman.

- Objective Psychology – an approach or attitude in psychological research that emphasizes measurement of observable phenomena, such as behavior (contrast: Subjective Psychology, under Phenomenology)

- Reinforcement Theory – the principle that, for learning to occur, there must be some type of reward or feedback. The notion is explicitly stated by almost all Behaviorisms and is assumed in most other discourses on learning. Two types of reinforcers were initially identified:

- Primary Reinforcer – a reinforcer that is necessary to the survival of the organism (e.g., food)

- Secondary Reinforcer – a neutral stimulus that gains importance when paired with a Primary Reinforcer

- Accidental Reinforcement (Adventitious Reinforcement) – as the phrase suggests, an unintended reinforcement that leads to the increased likelihood of an act. Accidental Reinforcement is often associated with superstitious behavior.

- Contingent Reinforcement – reinforcement that is only given when a behavior occurs

- Noncontingent Reinforcement – used mainly to gain and maintain a learner’s attention, a teaching strategy of delivering ongoing, minor reinforcement independent of the learner’s behavior

- Relativity Theory of Reinforcement (Probability Differential Hypothesis; Premack Principle; Grandma’s Rule) (David Premack, 1970s) – the suggestion that the opportunity to engage in a frequent (i.e., more-probable) behavior can be used to reinforce a less-frequent (less-probable) behavior

- Vicarious Reinforcement/Punishment – an increase/decrease in a specific behavior that results from observing the consequences of others’ behavior

Commentary

Originally, proponents of Behaviorisms regarded the process of creating links between environmental stimuli and the individual’s responses as predictable and mechanical – manageable through well-timed rewards and punishments. While this focus affords powerful insight into a wide swath of human behavior, it has also proven inadequate to account for such defining qualities of humanity as creativity and altruism. Criticisms of Behaviorisms often revolve around perceptions that coercive agents often act with uncritical understandings of dysfunction, and are thus inappropriately seeking one or more of:- Behavior Control – a coercive agent endeavors to control major (or, perhaps, all) aspects of a subject’s physical existence

- Thought Control – a coercive agent endeavors to control a subject’s thought processes

- Emotion Control – a coercive agent endeavors to control a subject’s feelings, attitudes, and responses

- Mathematical Learning Theory (Hull’s Mathematico-Deductive Theory of Learning) (Clark, L. Hull, 1930s) – Mathematical Learning Theory is not about learning mathematics, but about describing and explaining behavior in precise, quantitative terms. The theory emphasizes both Classical Conditioning and Operant Conditioning, and it is distinguished by its many postulates and corollaries, which are associated with different behaviors.

Subdiscourses:

- Accidental Reinforcement (Adventitious Reinforcement)

- Acquired Response (Learned Response)

- Associative-Chain Theory (Associative Chaining Theory)

- Behavior Control

- Behavior Theory (General Behavior Theory)

- Behavioral Cusp

- Behavioral Plasticity

- Behaviorist Learning

- Black Box

- Centralism (Centralist Psychology)

- Chaining (Sequential Learning)

- Cognitive Behavior Theory (Cognitive Behaviorism)

- Conditioning

- Configural Learning

- Contingent Reinforcement

- Descriptive Behaviorism

- Emotion Control

- Epiphenomenalism (Conscious Automatism)

- Equipotentiality

- Factor Theory of Learning

- Involuntary Response

- Mathematical Learning Theory (Hull’s Mathematico-Deductive Theory of Learning)

- Neobehaviorism

- Noncontingent Reinforcement

- Objective Psychology

- Peripheralism (Peripheralistic Psychology)

- Primary Reinforcer

- Reinforcement Theory

- Relativity Theory of Reinforcement (Probability Differential Hypothesis; Premack Principle; Grandma’s Rule)

- Response Chain (S–R Chain; Stimulus–Response Chain)

- S–O Association

- S–O–R Psychology (Stimulus–Organism–Response Psychology)

- S-R Learning (Stimulus–Response Learning)

- S–R Psychology (S–R Theory; Stimulus–Response Psychology)

- S-R-O Learning (Stimulus–Response–Outcome Learning)

- S–(R–O) Model (Stimulus–(Response–Outcome) Model)

- S-S Learning (Stimulus–Stimulus Learning; Stimulus Substitution Theory)

- S–S Psychology (Stimulus–Stimulus Learning Model)

- Secondary Reinforcer

- Stimulus–Response Association (Stimulus–Response Association; S-R Bond)

- Thought Control

- Two-Factor Theory of Learning

- Vicarious Reinforcement/Punishment

- Voluntary Response

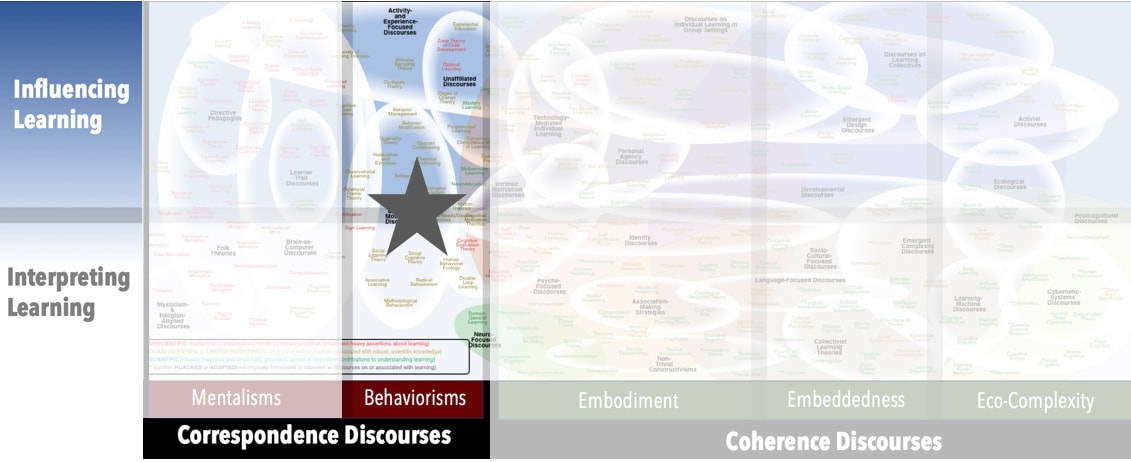

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Behaviorisms” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List