Focus

Processes associated with generating and using knowledgePrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … information

- Knowing is … using information

- Learner is … an information processor (individual)

- Learning is … inputting (and associated computer-based notions, such as processing, storing, and retrieving)

- Teaching is … transmission (of information)

Originated

1950sSynopsis

Cognitive Processes are typically understood to be brain-based phenomena that are associated with generating new knowledge and using established knowledge. Such processes include such variously and vaguely defined phenomena as attention, formation of knowledge, memory, judgment, evaluation, reasoning, computation, decision making, comprehension, and language use. In general, such processes are understood to improve with age and experience, and so Cognitive Processes are often associated with Developmental Discourses. Associated constructs include:- Processing Speed – a counterpart to speed-based notions associated with the Attainment Metaphor (see Quickness (Delayed; Slowness; Retardation) Metaphor under Medical Model of (Dis)Ability), Processing Speed emerges from the grounding metaphors of Brain-as-Computer Discourses. It refers to the pace at which a learner makes appropriate sense or takes appropriate action.

- Mental Chronometry (Cognitive Processing Speed) – a formalization of Processing Speed that’s used by some researchers, expressed as the time it takes one to react to a sensory stimulus (i.e., the construct is based on a brain-as-computer metaphor, but the actual measurement isn’t)

- Executive Functions (Central Processes; Cognitive Control; Control Processes; Executive Control; Higher Order Processes) – those Cognitive Processes that are seen as necessary for managing one’s own thoughts, perceptions, and actions. Typically, one’s Executive Functions are described as being governed by one of two attitudes:

- Action Orientation – having the ability to respond swiftly and appropriately to high-pressure situations

- State Orientation – having the tendency to become entangled in assessing circumstances and weighing options when caught in high-pressure situations

- Attention Regulation – one’s awareness of and control over one’s Attention (see Cognitive Science). In classroom contexts, Attention Regulation is typically characterized in terms of alertness and staying on task. Aspects of Attention Regulation include:

- Controlled Attention (Attentional Control; Directed Attention; Executive Attention; Selective Attention) – one’s capacity to determine what to focus on and what to ignore

- Sustained Attention – one’s ability to keep one’s Attention on a specified focus or activity for an extended period

- Fast Mapping (Susan Carey, Elsa Bartlett, 1970s) – construing an appropriate meaning of a new concept by associating it with elements encountered in the same spatial-temporal situation

- General Intelligence (Raymond Cattell, 1960s): a combination of Fluid Intelligence and Crystallized Intelligence:

- Fluid Intelligence (Fluid Abilities) (Raymond Cattell, 1960s) – one’s capacity to solve new reasoning problems, making minimal demands on prior learnings. Associated abilities include memory span and mental speed, which peak when young and decline with age.

- Crystalized Intelligence (Raymond Cattell, 1960s) – one’s ability to apply prior learnings to solve abstract problems – in particular, by applying logic or other formal reasoning skills. Associated abilities include language, social competencies, and cultural awarenesses.

- Inhibitory Control (Response Inhibition) – one’s ability to suppress natural and learned impulses

- Metacognition – “thinking about thinking” – that is, being critically aware of perceptions and interpretations as they happen

- Pattern Recognition – experiencing a new object or event as familiar by associating some structural aspect of that experience with memories of prior experience(s). Specific theories of Pattern Recognition are typically either “top-down” (imposing an established interpretation) or “bottom-up” (analyzing and reassembling a sensory experience). Specific examples include:

- Template Matching Theory – a top-down theory based explicitly on a principle of Representationalism – namely, that cognition involves assembling internal representations (or templates) of external reality – this perspective suggests that perception is a matter of comparing established templates to new sensory inputs

- Prototype Matching Theory – a top-down theory based explicitly on a principle of Representationalism – namely, that cognition involves assembling internal representations (or templates) of external reality – this perspective suggests that perception involves creating abstract prototypes (i.e., “average” or “typical” representations) that are used to interpret new sensory inputs

- Feature Analysis Theory (Detection Theory; Factorial Learning; Feature Detection Theory; Human Feature Learning; Signal Detection Theory) – a bottom-up theory of perception that posits that specific neurons (or groups of neurons) encode specific perceptual features, and that different levels of neuronal organization enable perception of relationships among features – and so perception happens when new sensory input activates different neurons (and groups of neurons, and levels of neuronal organization) that are associated with different features and relationships among features

- Feature Integration Theory (Anne Triesman, Garry Gelade, 1980s) – a theory of attention that describes it as a process of automatically and simultaneously registering multiple separate features of an object that are later integrated

- Planning – one’s ability to think through and across the activities associated with accomplishing a task or reaching a goal

- Working Memory (Active Memory) – one’s capacity to manage and manipulate Short-Term Memory (see Memory Research)

- Cognitive Flexibility Theory – “cognitive flexibility” refers to one’s ability to spontaneously reconfigure one’s understandings in ways to adapt to novel and dynamic situations

- Cognitive Resource Theory – founded on the assumption that brain resources are finite, the suggestion that heavy demands for one cognitive process (e.g., recall, encoding) will diminish activity or availability of others. (Note: There is another Cognitive Resource Theory; see Change Management.)

Commentary

To understand the construct of Cognitive Processes, some context is necessary – starting with the term “cognition.” Most definitions of cognition present it as a synonym of learning, with a strong emphasis on mental activity and abilities. Notably, while cognition has been a word in English for centuries, its use has increased 10,000-fold since the 1950s (Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer) – and the reason for that growth is instructive. Its rise corresponds to the emergence of Cognitivism, Information Processing Theory, and other discourses that are based on the metaphor “brain as computer.” These discourses began to emerge in the 1950s – and, with them, a subtle distinction was proposed between learning (as inputting) and cognition (as processing). That distinction is essential for making sense of the grab bag of constructs that have been identified as Cognitive Processes. That said, and to be fair, over recent decades, some of those constructs have come to be associated with robust scientific research.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

DiffuseStatus as a Theory of Learning

Cognitive Processes do not constitute a coherent discourse, although individual processes can be useful as descriptive tools in discussions of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

While not a discourse on teaching, Cognitive Processes appear to have been growing in popularity among educators, as both goals and means of learning.Status as a Scientific Theory

As noted above, it is not appropriate to interpret “Cognitive Processes” as a coherent discourse on learning. Some of its elements have proven to be especially powerful means for making sense of and/or influencing learning in classrooms; other aspects seem to be either too vague or too varied to be of much use to educators. Owing to this motley reputation, this category of discussion does not meet our criteria to be described as scientific.Subdiscourses:

- Action Orientation

- Attention Regulation

- Cognitive Resource Theory

- Controlled Attention (Attentional Control; Directed Attention; Executive Attention; Selective Attention)

- Crystalized Intelligence (Crystallized Abilities)

- Executive Functions (Central Processes; Cognitive Control; Control Processes; Executive Control; Higher Order Processes)

- Fast Mapping

- Feature Analysis Theory (Detection Theory; Factorial Learning; Feature Detection Theory; Human Feature Learning; Signal Detection Theory)

- Feature Integration Theory

- Fluid Intelligence (Fluid Abilities)

- General Intelligence

- Inhibitory Control (Response Inhibition)

- Mental Chronometry (Cognitive Processing Speed

- Metacognition

- Pattern Recognition

- Planning

- Processing Speed

- Prototype Matching Theory

- State Orientation

- Sustained Attention

- Template Matching Theory

- Working Memory (Active Memory)

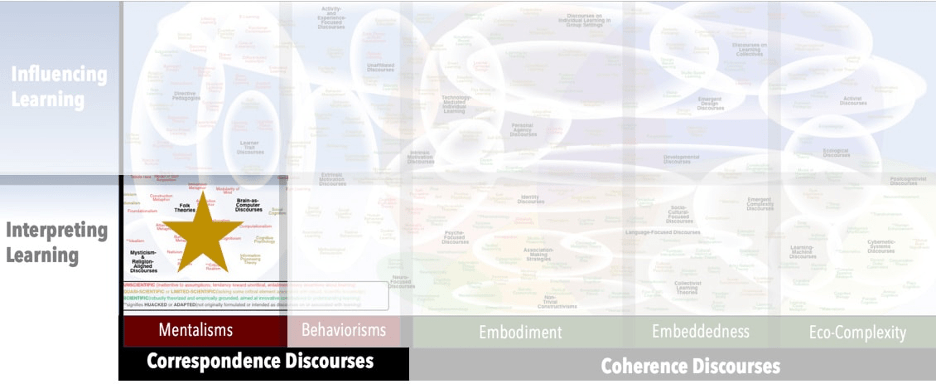

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2024). “Cognitive Processes” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List