Focus

Qualitative differences between the abilities of experts and novicesPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … expert-level skill and interpretation

- Knowing is … ability, expertise

- Learner is … a novice (individual)

- Learning is … improving, extending

- Teaching is … modeling, coaching

Originated

1980sSynopsis

The Expert–Novice literature develops the realization that the main difference between expert and novice performance is principally a matter of knowing differently rather than knowing more. Through prolonged experience, extensive practice, and intensive focus, the expert’s understandings are intricately networked and mainly tacit. Perceptions tend to be holistic, contributing to interpretations of complex situations in terms of coherent chunks. Performances typically appear fluid, automatic, and intuitive. The opposite can be said of the novice, whose understandings are likely fragmented. Complex situations may be perceived as chaotic and structureless, and performances can appear awkward and frustrating. Understandings of Expert–Novice are typically associated with a distinction between nonconscious/automatic and conscious/reflective systems of thinking. The evolution of that distinction through the 1900s included the following notions:- Knowledge by Acquaintance / Knowledge by Description (Bertrand Russell, 1910s) – Knowledge by Acquaintance is the “given” of knowing; the phrase applies to awarenesses developed through perceptual experience. Knowledge by Description is composed of those givens; the phrase applies to inferences, propositions, deductions, and other explicit assertions.

- Knowing-How / Knowing-That (Imperative, Performative, Practical, Procedural Knowledge versus Constative, Declarative, Descriptive, Propositional Knowledge) (Gilbert Ryle, 1940s) Knowing-That is a descriptor that applies to skilled performance. Knowing-That is a descriptor that applies to knowledge of specific facts.

- Tacit Knowledge / Explicit Knowledge (Implicit Knowledge / Explicit Knowledge; Unconscious Knowledge / Conscious Knowledge) (Michael Polanyi, 1950s) – Explicit Knowledge encompasses all understandings that are already or readily formalized, expressed, written, organized, and communicated. Its complement is Tacit Knowledge, which tends to be much more difficult to express – or, for that matter, even noticed. Tacit Knowledge tends to be embodied by knowers and embedded in systems. It is generally seen as prior to, vastly more extensive than, and necessary to the expression of Explicit Knowledge. These categories are associated with different types of learning:

- Bootstrapping (Quinian Bootstrapping) (Susan Carey, 2000s) – a version Top-Down Learning, in which it is posited that young children develop robust concepts by first memorizing symbols meaninglessly, later associating those symbols to actual phenomena and relating them to one another

- Bottom-Up Learning – developing Explicit Knowledge by deriving or extracting formal insights from already-developed Implicit Knowledge

- Implicit Learning – learning that happens without awareness or intention

- Top-Down Learning – developing Tacit Knowledge by assimilating, enacting, or embodying already-mastered Explicit Knowledge

- Unthought Known (Christopher Bollas, 1980s) – nonconscious past experiences that influence current thought and behavior

- Novice-to-Expert Methodology (Patricia Benner, 1980s) – a teaching approach that begins by comparing the actions, thought processes, and habits of experts and novices and then proceeds by structuring experiences intended to move the novice’s performance toward the expert’s

- Dual Process Theory (System 1 / System 2 Thinking; Automatic System / Reflective System) (Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, 1990s) – a contrast of two modes of thought: System 1, or the Automatic System, is memory-based – and so typically practiced, skilled, fast, and often experienced as instinctive or intuitive. System 2, or the Reflective System, is thinking-based – and so typically unpracticed, deliberative, slow, and often experienced as demanding and rule-based.

- Adaptive Expertise (Flexible Expertise) (Giyoo Hatano, Kayoko Inagaki, 1980s) – the cognitive and affective qualities associated with capacities to deal efficiently and effectively with novel demands (e.g., problem solving, generating new procedures, etc.)

- Beginner’s Mind (Shoshin) – derived from Buddhism, a term that describes the openness, eagerness, and preconception-free attitude when engaging with a new topic

- Sponge Activity – a busywork activity assigned to students to keep them occupied while the teacher attends to other pressing matters

- Thin Slicing (Nalini Ambady, Robert Rosenthal, 1990s) – a term from Psychology referring to the capacity to make rapid (“gut”) decisions based on very narrow window of experience (i.e., “thin slices” of information). For experts, Thin Slicing has been proven to be similarly accurate to decisions made over longer periods and based on much more information. Within education, the term has taken on many and diverse meanings, as the notion has been (mis)applied to activities as diverse as assessment, lesson planning, task design, and team-based examination of student performances.

Commentary

Criticisms of the Expert–Novice literature are relatively rare and muted. Few concerns are raised about the general constructs, but worries are sometimes voiced about extreme or overly rigid characterizations of differences. These is some debate over whether the transition from novice to expert is a continuum or whether it happens in distinct “quantum leap” stages/phrases. Unsurprisingly, several stage-based models have been proposed.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Anders EricssonStatus as a Theory of Learning

The Expert–Novice literature could be interpreted as advancing a distinct theory of learning, one that casts learning not as an accumulation of information but as elaborating or extending current possibility.Status as a Theory of Teaching

The Expert–Novice literature includes important insights into the sorts of practice that contribute most effectively to the development of expertise. For example, to move from “good” to “exceptional,” practice must be effortful (i.e., happening at the edge of current competence, where there’s a genuine risk of failure) and deliberate (aimed at focused awareness on fine-grained aspects rather than automaticity). While it is up to the individual to engage in this practice, most of the research points to the necessity of a teacher to help structure activities and to provide immediate and incisive feedback. In sum, then, while Expert–Novice is not a theory of teaching, it offers important practical advice to educators.Status as a Scientific Theory

The Expert–Novice literature is attentive to its metaphors and constructs around learning and teaching. It is supported by a substantial body of research that reaches across many domains of human activity. It is, in brief, a scientific theory.Subdiscourses:

- Adaptive Expertise (Flexible Expertise)

- Beginner’s Mind (Shoshin)

- Bootstrapping (Quinian Bootstrapping)

- Bottom-Up Learning

- Dual Process Theory (System 1/System 2 Thinking; Automatic System/Reflective System)

- Expertise (Classic Expertise; Routine Expertise; Technical Expertise)

- Implicit Learning

- Knowing-How / Knowing-That (Imperative, Performative, Practical, Procedural Knowledge versus Constative, Declarative, Descriptive, Propositional Knowledge)

- Knowledge by Acquaintance / Knowledge by Description

- Novice-to-Expert Methodology

- Tacit Knowledge/Explicit Knowledge (Implicit Knowledge/Explicit Knowledge; Unconscious Knowledge/Conscious Knowledge)

- Thin Slicing

- Top-Down Learning

- Unthought Known

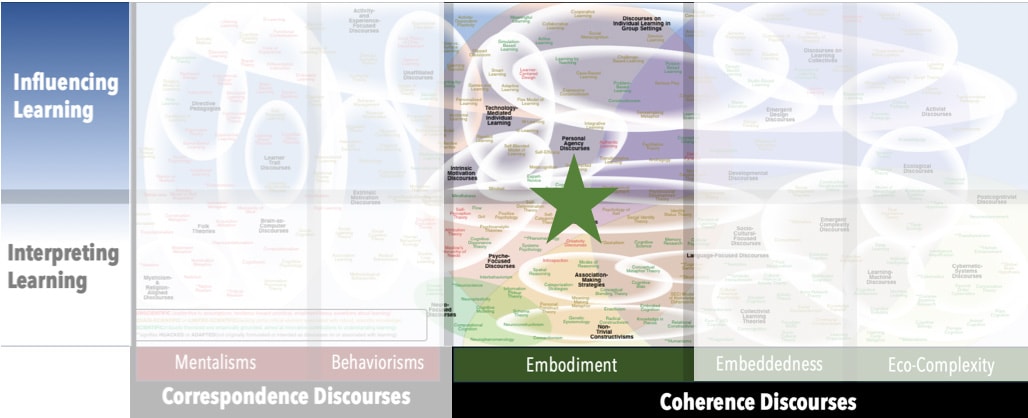

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2023). “Expert–Novice” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List