AKA

Introspective Learning

Metareasoning

Meta-Thinking

Focus

Roles of self-awareness and self-regulation in robust learningPrincipal Metaphors

Metacognition does not explicitly align with particular theories of learning, which means that almost any theory of learning can be aligned with it. Consequently, the theory makes just as much sense whether invoking the Acquisition Metaphor or the wildly incompatible Radical Constructivism. That said, on close analysis, the perspective most often invoked within Metacognition appears to fit most closely with the Illumination Metaphor:- Knowledge is … enlightenment; all that has been illuminated

- Knowing is … seeing

- Learner is … a see-er (individual)

- Learning is … coming to see (pulling into the light; overcoming darkness)

- Teaching is … showing; highlighting; shining a light on)

Originated

1970sSynopsis

Literally meaning “beyond knowing,” Metacognition refers to “thinking about thinking” – that is, being critically aware of perceptions and interpretations as they happen. More pragmatically, as a theory, Metacognition attends to abilities both to self-monitor and self-regulate. The principle that drives the theory is awareness of and control over study habits, attentiveness, memory, biases, comprehension, and other related capabilities will enhance learning. Identified elements of Metacognition include:- Intentional Learner (1970s) – associated with Metacognition, a term to describe one who actively and deliberately takes responsibility for their own learning process, continuously seeking knowledge, reflecting on experiences, and applying new insights to personal and professional growth

- Metacognitive Experiences (John Flavell, 1970s) – activities and engagements that require and/or support the development. of Metacognition

- Metacognitive Knowledge (Metacognitive Awareness) (John Flavell, 1970s) – one’s knowledge/awareness of one’s own and others’ cognitive processes

- Metacognitive Regulation (Regulation of Cognition) (John Flavell, 1970s) – skills used to manage one’s attentions and learning, such as planning, self-monitoring, and self-evaluating

- Cognitive Coaching – a formalized (and marketed) process aimed at mining and interrogating the personal assumptions and convictions that shape one’s practice – that is, to apply principles of Metacognition to one’s professional activity

- Cognitive Engagement (Paul Pintrich, 1990s) – paying attention to, monitoring understanding of, questioning, and otherwise thinking about the task and/or topics at hand

- Comprehension Monitoring (1980s) – periodic self-checks to ensure one is keeping pace with (i.e., understanding and remembering) lesson topics

- Conditional Knowledge – based on a distinction between Knowing-How / Knowing-That (see Expert–Novice), knowing when and why each is appropriate

- Critical Thinking – a process or competency associated with making decisions and solving problems, typically described as involving the collection, assessment, and use of information, as well as conscious awareness of one’s biases and thinking processes

- Instrumental Enrichment (Feuerstein Method) (Reuven Feuerstein, 1970s) – a teaching approach rooted in Cognitive Developmentalisms that aims to enhance learning potential through mediated learning experiences. Instrumental Enrichment emphasizes problem-solving, adaptability, and Metacognition, and helping individuals improve thinking skills regardless of age or ability.

- Judgment of Learning – awareness of the extent to which one has already learning material that is to be learned

- Know Thyself (Greek: γνώθι σε αυτών) – a dictum inscribed over the entrance of the Temple of Apollo, urging visitors to be self-aware. It has been associated with Metacognition since the term was coined.

- Learning How to Learn – a hodgepodge of techniques and (often commercial) programs that coalesce around the core principle of Metacognition – that is, awareness of and control over one’s cognitive habits enables and amplifies learning. Beyond that point, advice varies dramatically, depending on promoters’ beliefs and motivations. Illustrative examples include:

- 1,000× (Pranay Prakash, 2010s) – a set of strategies exaggeratedly purported to speed learning 1,000-fold. Suggestions include finding optimal resources, applying knowledge immediately, and understanding complementary skills.

- Mental Coaching – a strategy aimed at increasing concentration, improving performance, bolstering confidence, managing pressure, and reducing errors by helping the learner to focus on the cognitive features of a desired activity. That is, Mental Coaching is, in effect, a tactic to scaffold Metacogntion.

- Meta Learning (Meta-Learning) (Donald B Maudsley, 1970s) – the process of learning about one’s own learning – that is, of increasing self-control of learning processes through growing awareness of habits of perception, personal assumptions, strategies for inquiry, etc.

- Mrs. Potter’s Questions – a series of straightforward questions intended to support student Metacognition by guiding reflection on learning events. Typically, those questions include: What were you trying to do? What went well? What would you do differently next time? Do you need any help?

- Self-Awareness Theory – an umbrella term that applies to any theory involving paying attention to oneself – including Metacognition, but most often with a focus on understanding self in comparison to and in relationship with others

- Thinking Through – a multistage process of trying to understand into one’s own thought processes, automatic reactions, habits, and so on

- Time on Task (Jere Brophy 1980s) – as the phrase suggests, the spent engaging in an assigned learning activity. Time on Task tends to be strongly correlated with academic success.

- Calibration (G. Keren, 1990s) – the extent to which one’s self-assessment of a performance matches with more objective evaluations of that performance (compare eal–Ideal Self Congruence, below)

- Meta-Attention – one’s awareness of the influences on one’s own attentions

- Metacomprehension (various, 2000s) – the ability to monitor and reflect on understanding of texts

- Metaemotion – one’s awareness of one’s own and others’ emotions, which includes awareness of one’s emotional responses to manifesting and/or triggering various emotions

- Metalinguistic Awareness (Linguistic Awareness) – an indicator of the emergence of one’s Metacognition that typically begins to manifest at about age 8, the conscious awareness of and capacity to appropriately generality the functional and semantic properties of language

- Metamemory – one’s awareness of memory processes, usually engaged for the purposes of honing memory

- Metastrategic Knowledge (Anat Zohar, 2000s) – a component of Metacognition that comprises critical awareness of cognitive processes and higher-order thinking strategies

- Real–Ideal Self Congruence – the extent to which one’s perception of one’s own abilities and qualities is consistent with more objective assessments of those traits (compare Calibration, above)

Commentary

There are two major categories of criticism of Metacognition. Firstly, the theory is inattentive to the natures of learning and cognition, thus offering a theory that can be pasted onto naïve and trivial theories of learning. Secondly, the theory is usually focused on the self, thus underplaying the importance of context and culture. (Compare Social Metacognition and Organizational Metacognition.)Authors and/or Prominent Influences

DiffuseStatus as a Theory of Learning

Metacognition is not a theory of learning. Metacognition does not include consideration or critique of its own assumptions about the nature of learning or the metaphors used to characterize learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Metacognition is quite popular among educators, as might be inferred from the associated discourses mentioned above.Status as a Scientific Theory

Metacognition and its associated discourses have been bolstered by evidence both that (1) metacognitive skills can be developed with support and effort and (2) those with stronger metacognitive skills work more efficiently, are less distracted, and do better on examinations.Subdiscourses:

- Calibration

- Cognitive Coaching

- Cognitive Engagement

- Comprehension Monitoring

- Conditional Knowledge

- Critical Thinking

- Instrumental Enrichment (Feuerstein Method)

- Intentional Learner

- Judgment of Learning

- Know Thyself

- Learning How to Learn

- Mental Coaching

- Meta-Attention

- Metacognitive Experiences

- Metacognitive Knowledge (Metacognitive Awareness)

- Metacognitive Regulation (Regulation of Cognition)

- Metacomprehension

- Metaemotion

- Meta Learning (Meta-Learning)

- Metalinguistic Awareness (Linguistic Awareness)

- Metamemory

- Metastrategic Knowledge

- Mrs. Potter’s Questions

- 1,000×

- Real–Ideal Self Congruence

- Self-Awareness Theory

- Thinking Through

- Time on Task

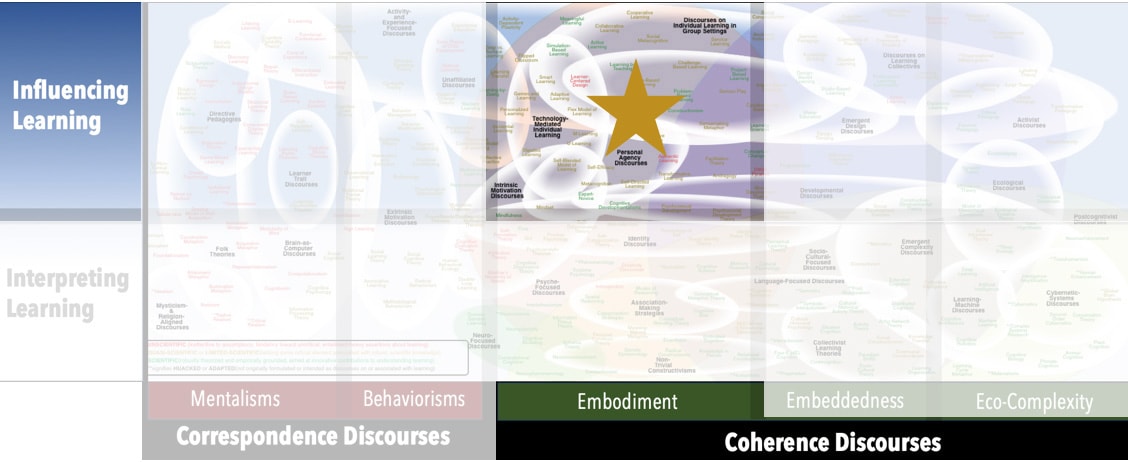

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Metacognition” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List