AKA

Self-Theories

Focus

The relationship between one’s sense of agency and one’s learning engagementsPrincipal Metaphors

Mindset offers a contrast between those who see their learning-related traits as fixed/pre-given and those who see them in terms of growth and expansive possibility. Each is associated with distinct clusters of metaphors:| Fixed Mindset | Growth Mindset |

|

|

Originated

1990sSynopsis

The most popular version of Mindset, developed by Carol Dweck, is focused on the relationship between learners’ conceptions of themselves and their attitudes toward learning. It distinguishes between two types of mindset, fixed and growth:- Fixed Mindset (Carol Dweck, 1990s) – Learners with a fixed mindset typically see ability as fixed and learning in terms of a performance that reflects that ability.

- Growth Mindset (Carol Dweck, 1990s) – Learners with a growth mindset typically see ability in more expansive terms, defined at least in part by the effort put forth.

- Achievement Goal Theory (Achievement Orientation Theory; Goal Orientation Theory; Goal Perspective Theory) (Carol Dweck, Carole Ames, 1980s) – a perspective that highlights the impact of goal orientation on learning strategies, motivation, and overall academic and personal success. Two kinds of achievement goals are distinguished:

- Mastery Goal (Ego Goal) (Carol Dweck, 1980s) – a learning goal that’s focused on improving one’s skills and understanding

- Performance Goal (Task Goal) (Carol Dweck, 1980s) – a learning goal that’s motivated by desires to outperform others and to gain favorable judgments of one’s performance

- Implicit Self Theory (Carol Dweck, 1980s) – the suggestion one holds either an Entity Theory or an Incremental Theory of onself:

- Entity Theory – the perspective that psychological traits (e.g., personality, emotion, ability, intelligence) are thing-like – that is, fixed – and so cannot be much affected

- Incremental Theory – the perspective that psychological traits (e.g., personality, emotion, ability, intelligence) are malleable and can be improved though learning and practice

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (Robert K. Merton, 1940s) – the notion that pre-established beliefs will orient and channel actions in a way that those beliefs become a reality.

- Fundamental Attribution Error (Attribution Bias; Attribution Effect; Correspondence Bias) (Lee Ross, 1960s) – when assigning responsibility for a person’s behaviors, the tendency to over-emphasize personal qualities (e.g., disposition) to and under-emphasize situational factors

- Learned Helplessness (Helplessness Theory) (Martin Seligman, 1960s) – Formally: an internalized conviction, rooted in experiences in which outcomes are independent of one's efforts, that one can do nothing to ease ongoing trauma. Popularly: a learned reliance on available help, which often manifests as a powerlessness or reluctance to engage in demanding tasks.

- Pygmalion Effect (Robert Rosenthal & Lenore Jacobson, 1960s) – pulling from the title of George Bernard Shaw’s play, the Pygmalion Effect is a type of Self-Fulfilling Prophecy associated with educators' influence. It is simultaneously an alert that educator expectations might be reflected in learner performance and an admonition to set expectations high.

- Golem Effect (E. Babad, 1970s) – a type of Self-Fulfilling Prophecy in which low expectations (of selves, or by leaders) contribute to poor performance

- Self-Handicapping (Edward E. Jones & Steve Berglas, 1970s) – a strategy used to damage self-esteem by avoiding situations that might lead to failure – by, for example, structuring responsibilities so that blame can be deflected from oneself

- Uncertainty Avoidance vs. Uncertainty Orientation (Geert Hofstede, 1970s) – Uncertainty Avoidanc is the tendency to stay with what is familiar (contexts, activities, beliefs, etc.). Uncertainty Orientation is the tendency to seek out the unfamiliar and to live comfortably in the space of uncertainty. The notions can be applied at both collective-cultural and individual-psychological levels, but most often the former

- Proleptic Teaching (C. Addison Stone, James Wertsch, 1980s) – derived from Greek prolepsis “an anticipating,” a teaching attitude founded high expectations and confident belief that learners will meet those expectations. The notion is often blended with Scaffolding (under Socio-Cultural Theory), leading to the advice to provide support for learners in activities that are just beyond their current levels of independent competence.

- Winner Effect (Alan Booth, 1980s) – an instance of Positive Feedback (see Cybernetics) in which success in competitions or challenges contributes to subsequent successes

- Learned Industriousness (Robert Eisenberger, 1990s) – better performance of some despite similar abilities to others emerging from perseverance, which is argued to be motivated by greater reinforcement

- Learned Optimism (Martin Seligman, 1990s) – the idea that personal optimism can be actively cultivated by rethinking reactions to adversity

- Neuroplasticity (1990s) – the brain’s ability to change throughout the lifespan – including, but not limited to: strengthening and weakening of synapses, establishing and losing connectivity, transfer of functions to different locations, and changes to proportions of grey matter

- Stereotype Threat (Claude Steele, Joshua Aronson, 1990s) – a conscious awareness, often associated with fear or anxiety, of the risk of conforming to the ascribed traits of an identifiable group. In education, the phenomenon has been associated with race-, gender-, and class-based gaps in academic performance.

- Destiny Instinct (Hans Rosling, 2010s) – the belief that people, cultures, or countries have fixed characteristics that determine their future, leading to assumptions that things will always stay the same. Within education, the notion has been used to analyze educators’ and policymakers’ attitudes toward student potential, cultural adaptability, and systemic change.

- Learner Mindset vs. Judger Mindset

- Learner Mindset (Marilee Adams, 2000s) – a way of acting/being associated with approaching situations with curiosity, openness, and a focus on understanding and growth

- Judger Mindset (Marilee Adams, 2000s) – a way of acting/being associated with hasty reactions, quick evaluations, unconsidered criticism, and not-necessarily-justified certainty

- Mind-Set (Mindset Theory of Action Phases) (Peter Gollwitzer, 2010s): a delineation of two sets of cognitive procedures that are involved with setting and reaching goals:

- Deliberative Mind-Set (Peter Gollwitzer, 2010s) – one critically examines the issues around choices for action associated with possible goals

- Implemental Mind-Set (Peter Gollwitzer, 2010s) – one undertakes a specific set of actions to reach a selected goal

- Paradox Mindset vs. Either/Or Mindset

- Paradox Mindset (Both/And Mindset) (Wendy Smith, Marianne Lewis, 2000s) – a habit of thinking or way of being that embraces the idea that opposing demands (like work-life balance, or innovation vs. efficiency) can not only co-exist but enhance each other

- Either/Or Mindset (Wendy Smith, Marianne Lewis, 2000s) – a habit of thinking or way of being that frames the world in terms of radical divisions and conflicting choices, according to which my must just one option/side at the expence of the other

- Stress Mindset Theory (Alia Crum, 2010s) – a framework that explores how individuals' beliefs about stress influence their physical, emotional, and behavioral responses to it. Two mindsets about stress are posited:

- Stress-is-Enhancing Mindset (Alia Crum, 2010s) – experiencing stress as an opportunity for growth, learning, and improved performance, typically associated with embracing challenges and using stress to fuel growth

- Stress-is-Debilitating Mindset (Alia Crum, 2010s) – experiencing stress as harmful to health, performance, and well-being, typically associated with avoiding stressful situations and feeling overwhelmed

Commentary

It is not clear whether Mindset offers distinct categories or poles on a continuum. Commentators who interpret the theory in terms of distinct categories typically accuse it of being reductive – and yet another way of assessing and categorizing children. More troubling, the discourse appears to have been used to displace blame for poor teaching onto learners (who, according to the discourse, are occupying the wrong mindset or not trying hard enough).Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Carol DweckStatus as a Theory of Learning

Mindset is more of a description of a psychological phenomenon than a theory of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Mindset is perhaps more appropriately construed as a theory of teaching than a theory of learning or learners. It offers extensive commentary and advice on the connection between teachers’ emphases and learners’ mindsets.Status as a Scientific Theory

Although tremendously popular within education, Mindset does not have the empirical base that is commonly assumed. Significantly, Dweck’s original research on Mindset has not been replicated.Subdiscourses:

- Achievement Goal Theory (Achievement Orientation Theory; Goal Orientation Theory; Goal Perspective Theory)

- Deliberative Mind-Set

- Destiny Instinct

- Either/Or Mindset

- Entity Theory

- Fixed Mindset

- Fundamental Attribution Error (Attribution Bias; Attribution Effect; Correspondence Bias)

- Golem Effect

- Growth Mindset

- Implemental Mind-Set

- Implicit Self Theory

- Incremental Theory

- Judger Mindset

- Learned Helplessness (Helplessness Theory)

- Learned Industriousness

- Learned Optimism

- Learner Mindset

- Mastery Goal (Ego Goal)

- Mind-Set (Mindset Theory of Action Phases)

- Paradox Mindset (Both/And Mindset)

- Performance Goal (Task Goal)

- Proleptic Teaching

- Pygmalion Effect

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Self-Handicapping

- Stereotype Threat

- Stress Mindset Theory

- Stress-is-Debilitating Mindset

- Stress-is-Enhancing Mindset

- Uncertainty Avoidance

- Uncertainty Orientation

- Winner Effect

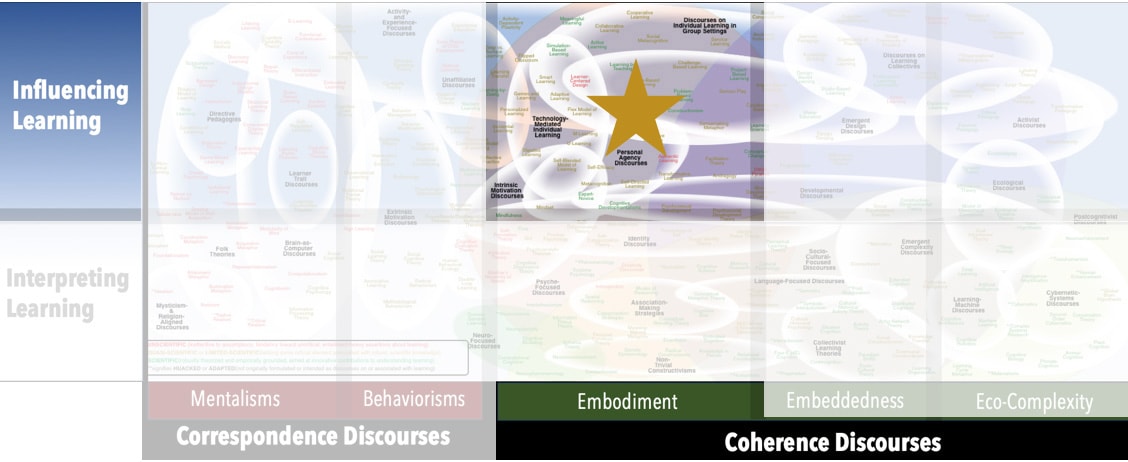

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Mindset” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List