AKA

Learning Through Play

Ludology

Focus

What might be learned during playPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … scope of possible actions

- Knowing is … appropriate action

- Learner is … an intentional agent

- Learning is … developing

- Teaching is … varied according to conception of “play” – from abandoning to structuring

Originated

ancientSynopsis

Play-Based Learning attends to what might be learned during play – a focus that, of course, is dependent on how “play” is defined. To that end, play is almost always considered to be agent-directed and intrinsically motivated:- Play – activity that is done for its own sake – thus, spontaneous, voluntary, unstructured, pleasurable, and flexible. Depending on age, Play can involve interactions of body parts, with objects, with others, and/or with ideas.

- Surplus Energy Theory of Play (Friedrich Schiller; Herbert Spencer, 1870s) – the suggestion that the principal purpose of play is to release pent-up energy

- Recreation Theory of Play (Relaxation Theory of Play) (Moritz Lazarus, 1880s) – the suggestion that the play is restorative, and so its principal purpose is to re-center and re-energize through amusements that are relaxing, distracting, and de-stressing.

- Practice Theory of Play (Anticipatory Theory of Play; Pre-Exercise Theory) (Karl Groos, 1890s) – the suggestion that the principal purpose of play is to prepare children for adult activities, responsibilities, and relationships

- Cathartic Theory of Play (Sigmund Freud, 1900s) – the suggestion that play serves as a means either to satisfy drives or to resolve conflicts (at least temporarily), especially when no other options for necessary catharsis are available

- Growth Theory (L.E. Appleton, 1910s) – the suggestion that, across species, the principal purpose of play is to become familiar with and exercise the attitudes and skills necessary for survival in adulthood

- Infantile Dynamics (Kurt Lewin, 1930s) – the suggestion that play arises in the fact that the child is unable to distinguish the real from the unreal, and so occupies a space of constant change and arbitrary possibility

- Motor Skills – mastery of control and accuracy in deliberate bodily movements

- Phases of Motor Development (Jane E. Clark, 1990s) – a stage-based developmental model that separate mastery of motor skills into four phases:

- Reflexive Movement Phase – ages 0–1 year, characterized by involuntary movements that afford information about immediate surroundings

- Rudimentary Movement Phase – ages 1–2 years, characterized by shifts from involuntary to voluntary actions as one’s ability to control the body emerge

- Fundamental Movement Phase – ages 2–7 years, characterized by increased control of gross and fine motor skills

- Specialized Movement Phase – ages 7–on, characterized by progressive refinement of stability, locomotor, and manipulative skills that are combined and applied across ranges of activities

- Locomotor Play – vigorous, physical activity that involves sustained, exaggerated, and repetitious movements. Subtypes include:

- Rhythmic Stereotypy – repetitive gross movement (e.g., body rocking), usually diminishing by 1 year of age

- Exercise Play – activity involving vigorous, full-body movements (e.g., running, jumping, climbing). Exercise Play typically emerges at age 2 and peaks at about age 5 years.

- Rough-and-Tumble Play – vigorous bodily activity the involves physical contact with others

- Object Play – activity that involves shifting, organizing, throwing, or otherwise manipulating objects in one’s environment

- Social Play – activity that involves others, typically for amusement or competition. Social Play also includes “pretend” or role play.

- Exploratory Play – usually associated with toddlers and young children, a type of play that involves deliberate use, scrutiny, and testing of artifacts. In terms of personal growth, Exploratory Play is seen to contribute mainly to cognitive development.

- Functional Play – usually associated with infants and toddlers, the sort of play that, to the observer, appears to be engaged for its own sake and to be maintained for as long as it gives pleasure. In terms of personal growth, Functional Play is seen to contribute to cognitive, motor, and social-emotional development.

- Nature Play – unstructured, child-initiated play in natural areas and/or with non-domesticated lifeforms. In terms of personal growth, Functional Play is seen to contribute to cognitive and motor development, and especially to social-emotional development.

- Object-Oriented Play – Play that involves focused exploration/examination of physical aspects (i.e., objects and materials) of one’s experience. Object-Oriented Play is asserted by many to be one of the most prominent and significant activities during early childhood.

- Open-Ended Play – child-directed play that has few constraints apart from the limitations of the setting. Open-Ended Playis often associated with materials that can be used or shaped in many ways, such as building blocks, paper, playdough, and paint

- Sociodramatic Play – the taking on of a social role (e.g., a parent, or a store clerk), usually in interaction with others

- Symbolic Play (Joe Frost, 2000s) – the use of objects, actions, and/or ideas to stand in for other objects, actions, and/or ideas. Specific types of Symbolic Play include:

- Dramatic Play – a type of Symbolic Play in which one imitates another’s actions and speech

- Pretend Play – a type of Symbolic Play in which one assigns roles or characters to inanimate objects or participants

- Role Play – a type of Symbolic Play in which one takes on a make-believe role, which can be fantastical or familiar

- Parten’s Six Stages of Play (Mildred Parton, 1920s) – a developmental progression of modes of Play that are suƒpracticggested to emerge through the first five years of a child’s life

- Unoccupied Play – body motions engaged by infants and toddlers, typically with no deliberate purpose, but perhaps driven by feelings of pleasure and curiosity

- Independent Play (Solitary Play) – playing alone, disconnected from, uninfluenced by, and likely oblivious to others

- Onlooker Play – observing other agents at play, but not engaging in that play

- Parallel Play – playing beside but not with other agents, often with the same toys or oriented by the same goal

- Associative Play – playful interaction with other agents, but not necessarily for the same reasons

- Cooperative Play – play involving other agents that is oriented by a common purpose

- Constructive Play (Walter Drew, 2000s) – activity in which one is free to manipulate aspects of one’s environment – by assembling, dissembling, drawing, moving, etc. – thus enabling hands-on inquiry that might support development of the imagination, of problem-posing and problem-solving abilities, of fine motor skills, of self-knowledge, and of social skills

- Explearning – a portmanteau of “exploring,” “playing,” and “learning” that is used by multiple educational institutions and agencies, as well as several companies (mainly with interests in educational toys and games)

- Free Play – unstructured, agent-directed activity subject to subtle constraints and/or located within a planned space, designed to channel attentions and actions in ways that contribute to broad clusters of competencies

- Guided Play – flexible activity within defined constraints (see, e.g., Learning Toys and Tools and Games and Learning) that is geared toward specific learning goals and that is typically supported by more expert knowers

- Ludic Learning (Ludic Pedagogy) – from the Latin ludere “to play,” the incorporation into one’s teaching of elements designed promote fun and play

- Make-Believe Play – pretending and role play that afford opportunities to test and practice wide arrays of culturally appropriate skills and identities while developing understandings of the inner dynamics of complex social situations

- Object-Oriented Play – Play that involves focused exploration/examination of physical aspects (i.e., objects and materials) of one’s experience. Object-Oriented Play is asserted by many to be one of the most prominent and significant activities during early childhood.

- Organized Play – Play that involves rules, orderly participation, and that is structured by someone other than the player(s)

- Risky Play (Rusty Keeler, 2020s) – a type of play that presents a genuine risk of injury, which is argued to support learners’ emerging understandings of the limits of their abilities and the qualities of “safe activity, all while bolstering senses of self-responsibility

- Serious Play – a range of play-based, problem-focused, and inquiry-oriented formats for learning that are intended mainly for adults and that are united across themes of flexibility in activity, toying with boundaries, oriented to possibility, and freedom from judgment – all while having fun

- Structured Play – organized and rule-governed Play that is typically overseen by an adult

Commentary

As might be inferred from the categories and subcategories listed above – which actually represent only tip of a large iceberg – Play-Based Learning is subject to a wide range of interpretations. Because the foundational notion is so hotly contested, some commentators argue discourse is doomed to incoherence, and this criticism seems to be validated regularly as, for example, an advocate of Free Play simultaneously endorses school uniforms, teacher-centered lessons, and summative assessments. Of course, none of this is to say that the notion of incorporating Play into formal education is a bad idea. On the contrary, it’s likely a very good one … but the matter is in need of more careful theorizing and investigation.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

DiffuseStatus as a Theory of Learning

Insofar as it is properly included among Developmental Discourses, Play-Based Learning contributes to understandings of how different modes of Play evolve and how manners of engagement within Play might contribute to learning across physical, cognitive, affective, and social competencies.Status as a Theory of Teaching

While Play-Based Learning is undertheorized and under-researched, it still offers some important insights for educators seeking to understand the complementarities of structured and unstructured experiences.Status as a Scientific Theory

In formal academic terms, Play-Based Learning is a relatively new area. There is an abundance of evidence that points to the value of Play-Based Learning in relation to matters of motivation and well-being, and rather less that affords insight in the contributions of Play into robust understandings of complex ideas. Consequently, in terms of scientific status, it appears to be a promising but under-developed domain.Subdiscourses:

- Associative Play

- Cathartic Theory of Play

- Constructive Play

- Cooperative Play

- Dramatic Play

- Exercise Play

- Explearning

- Exploratory Play

- Free Play

- Functional Play

- Fundamental Movement Phase

- Growth Theory

- Guided Play

- Independent Play (Solitary Play)

- Infantile Dynamics

- Locomotor Play

- Ludic Learning (Ludic Pedagogy)

- Make-Believe Play

- Motor Skills

- Nature Play

- Object Play

- Object-Oriented Play

- Onlooker Play

- Open-Ended Play

- Organized Play

- Parallel Play

- Parten’s Six Stages of Play

- Play

- Phases of Motor Development

- Practice Theory of Play (Anticipatory Theory of Play; Pre-Exercise Theory)

- Pretend Play

- Recreation Theory of Play (Relaxation Theory of Play)

- Reflexive Movement Phase

- Rhythmic Stereotypy

- Risky Play

- Role Play

- Rough-and-Tumble Play

- Rudimentary Movement Phrase

- Social Play

- Sociodramatic Play

- Specialized Movement Phase

- Structured Play

- Surplus Energy Theory of Play

- Symbolic Play

- Unoccupied Play

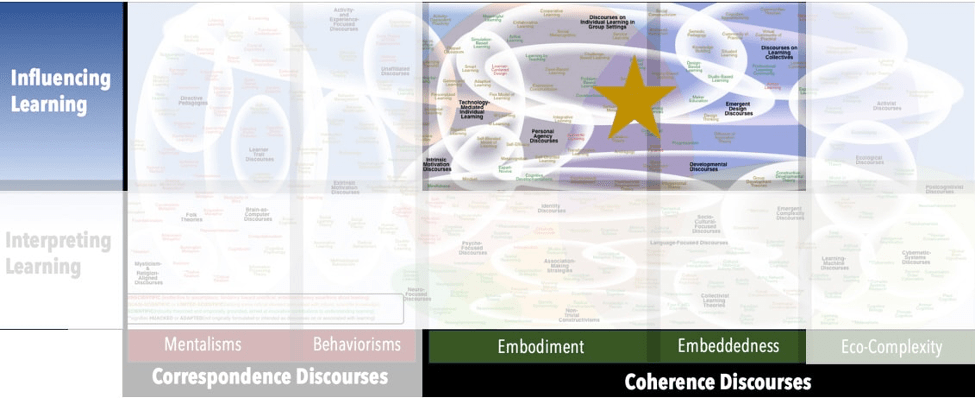

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2024). “Play-Based Learning” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List