Focus

Differentiating among modes of teachingPrincipal Metaphors

The word “teach” is derived from the Proto-Indo-European word deik- “to show, point out.” It is also related to the Old English tacn, meaning “sign” or “mark.” That is, the notion of teaching originally had to do with orienting attentions toward significant features. Given this background, and in consideration of that the word “learning” is derived from the Path-Following Metaphor, it’s perhaps not surprising notions and images of pointing figure so prominently in modern conceptions of teaching. (If you’re unconvinced, take a moment to do image searches of “teach,” “teaching,” and “teacher.”) Nor is it surprising that teaching has long been interpreted and enacted in terms of directing, leading, guiding, showing, focusing, and other acts of orienting. Thus, while there are many dozens of popular synonyms for teaching, those arising from following flock of metaphors are among the most prominent:- Knowledge is … a territory/area/domain/field (typically involving challenge)

- Knowing is … attaining a goal

- Learner is … a seeker (individual)

- Learning is … journeying (arriving at, reaching, progressing, accomplishing, achieving)

- Teaching is … directing, leading, guiding, showing, focusing

Originated

N/ASynopsis

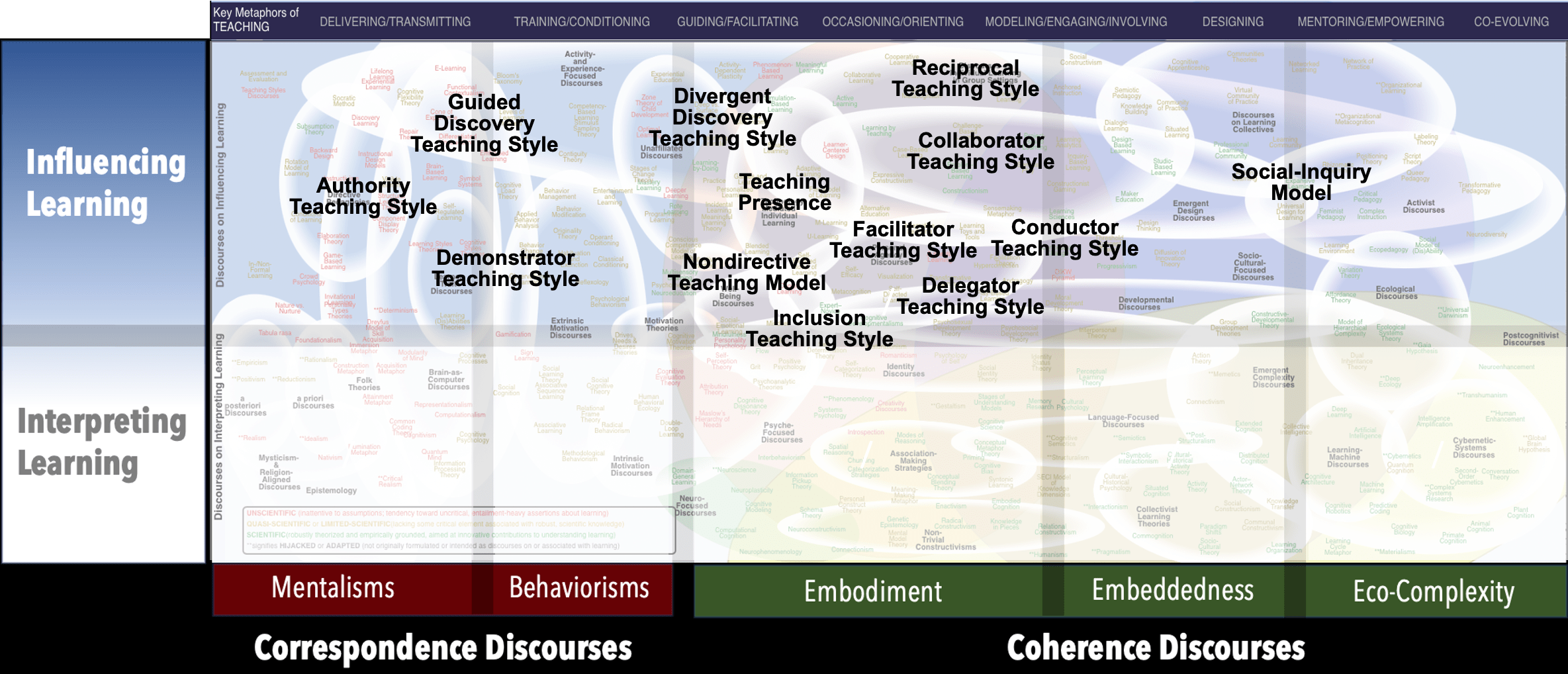

Teaching Styles Discourses include any attempt to identify and/or categorize modes of teaching. The least sophisticated efforts involve undifferentiated lists of teaching approaches, usually with brief descriptions that are infused with moral judgments and uncontextualized assertions on effectiveness. Slightly more sophisticated versions employ questionnaires and planar diagrams to assist users in locating themselves among two or more categories of distinction. (Note: To highlight contrasts and associations, we have “located” these discourses on the map at the bottom of the page.) A prominent, but not universal, theme across Teaching Styles Discourses is a quest for "Best Practice":- Best Practice (various, 1990s) – rooted in business, a Best Practice is a technique that is demonstrated by empirical evidence to be superior to alternatives. The notion has gained considerable traction in education over the past decade, sometimes in ignorance of the fact that o the metrics of effectiveness used by business (e.g., profit, growth, efficiency, quality) do not have direct correlates in education.

- Didactic Triangle (Johann Friedrich Herbart, 1820s) – a simple figure comprising an equilateral triangle with “teacher,” “learner,” and “knowledge” (or variations on those terms) at the vertices. Used for various purposes, the Didactic Triangle is most often invoked as a reminder of the importance of simultaneously considering all three of those interrelated elements.

- Signature Pedagogies (Shulman, 2000s) – discipline-specific and routinized modes of teaching, distinguished according to three structural qualities: surface structure (actual practices), deep structure (assumptions that underpin practices), and implicit structure (values and beliefs that orient the teaching).

Common distinctions within Teaching Styles Discourses

With regard to the three just-mentioned aspects of Signature Pedagogies, almost all Teaching Styles Discourses are focused on “surface structure.” That is, matters of “deep structure” and “implicit structure” tend to be assumed in simplistic distinctions, such as the following:- Teacher- vs. Student-Centered

- Teacher-Centered Learning (Instructor-Centered Learning) – a mode of teaching in which the student is positioned as passive – that is, the educator defines what will be learned, how it will be learned, and how the learning will be evaluated

- Student-Centered Learning (Child-Centered Learning; Learner-Centered Education) – a mode of teaching that takes up one of more of the following principles: (1) Students are treated as active participants in their own learning. (2) Teaching styles accommodate to differences among individuals. (3) Students participate in choosing topics, pacing lessons, and assessing outcomes

- Structured vs. Unstructured Learning

- Structured Learning – most often, a phrase that describes teaching styles associated with pre-analyzed subject matter, sequenced learning trajectories, and standardized performance expectations. (Structured Learning can also refer more specifically to the focused and intensive supports provided to meet the specific behavioral, emotional, and/or cognitive needs of a learner.)

- Unstructured Learning – a phrase the refers to the removal of constraints that are typical of formal schooling, but that does not specify which constraints are removed – and so Unstructured Learning might be applied to rejecting standard curricula, making tasks open-ended, avoiding classroom spaces, ignoring school formalities, and so on

- Generic vs. Differentiated Teaching

- Teaching to the Middle – a mode of teaching that is geared to the “average” learner, typically making few or no accommodations for those differently abled, less prepared, or more advanced

- Differentiated Instruction – a mode of teaching that is oriented by the conviction that learning is maximized when teaching is adjusted to each child’s learning needs and preferences.

- Fixed/Mandated/Imposed vs. Emergent Curriculum

- Fixed/Mandated/Imposed Curriculum – a program in which most or all topics of study are prespecified (typically, along with topic sequences, performance expectations, reporting requirements, and resource recommendations)

- Emergent Curriculum – any pedagogical attitude or approach that allows for flexibility, spontaneity, and deep exploration – most often applied to early education settings and typically attracting with such descriptors as open-ended, learner-centered, real-world, and interest-driven (See also Learning Design.)

Teacher Knowledge as an aspect of Teaching Styles Discourses

Increasingly, discussions of teaching styles are influenced or oriented by research into teachers’ knowledge of the disciplines they teach. Associated discourses include:- Didactics – in many European settings, the interdisciplinary study of learning and teaching, typically indexed to specific curriculum content (i.e., a publication oriented by Didactics is more likely to be about “learning mathematics” or “teaching reading” than to be a general discussion of learning or teaching). The word Didactics comes from the Greek didaktikos “apt at prompting learning,” from PIE *dens- “to learn.”

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) (Lee Shulman, 1980s) – an awareness of and facility with the metaphors, images, and other associations that are most likely to enable a learner to make coherent and appropriate sense of a concept. It is distinct from disciplinary mastery, which is more about automaticity with tightly packed concepts than explicit awareness of the elements that constitute those concepts. Associated constructs include:

- Teacher Cognition (Simon Borg, 2000s) – those traits of teachers that influence their attitudes and practices, including knowledge base, beliefs, philosophies, identifications, and positionalities

- TPACK (Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge) (Punya Mishra, Matthew Koehler, 2000s) – an elaboration of Pedagogical Content Knowledge within EdTech (see Technology-Mediated Individual Learning). Three areas of teacher expertise are idenfied: technological knowledge (TK), pedagogical knowledge (PK), and content knowledge (CK), reflecting a conviction that educators should continuously evaluate relationships among educational content, teaching practices, and learning resources.

- Sectioning – the practice of assigning multiple classes (“sections”) of the course to the same teacher to be taught in different time blocks through the day. The practice is often justified in terms of teachers' disciplinary knowledge (i.e., providing expert-led and consistent experiences to students), but the reasons often have more to do with efficiencies in scheduling, staffing, and resources.

Identified types of Teaching Styles

Regarding undifferentiated lists of teaching approaches, the following types are commonly encountered. (Notes: We have collapsed some categories, and we have rendered most descriptions generic. Different commentators have proposed specific variations for each entry, and some of those variations may conflict with our versions.):- Authority Teaching Style (Lecture Teaching Style; Command Teaching Style; Delivery Teaching Style; Directing Teaching Style; Expository Teaching; Direct Instruction) – a designated expert makes all decisions around intentions, actions, and measures and then presents information on preselected topics to attentive students who are responsible for ensuring adequate retention and/or comprehension of the material presented.

- Balanced Instruction (Balanced Teaching) – a diversely interpreted term that has been applied to a range of educational activities and structures. Prominent examples include varied lesson structures (which present a need for balance among whole class, small group, and independent instruction), varied learner preferences (which present a need to balance adapting to those preferences and employing other instructional methods), and so on.

- Collaborator Teaching Style (Discussing Teaching Style; Interaction Teaching Style) – focused on group process, this style involves students in presenting and challenging opinions through discussion, debate, and a range of research activities. The teacher’s roles include arbiter, participant, and more-experienced knower

- Conductor Teaching Style (Hybrid Teaching Style; Blended Teaching Style) – combining the teacher’s expertise with students’ interests, this approach employs a range of styles, as appropriate to the moment

- Delegator Teaching Style (Empowerment Teaching Style) – a student-centered approach in which the teacher sets the stage and self-positions as a consultant or resource, enabling students to define appropriate actions according to personal interests

- Demonstrator Teaching Style (Coaching Teaching Style: Modeling Teaching Style; Practice Teaching Style) – a designated expert makes all decisions around intentions, actions, and measures and then demonstrates appropriate actions, usually accompanied or followed by opportunity for students to mimic, practice, or apply those actions

- Developmental-Interaction Approach (Barbara Biber, Edna K. Shapiro, David Wickens, 1970s) – a model of teaching and classroom (inter)activity that blends the defining sensibilities of Developmentalist Discourses and Interactionism. The Developmental-Interaction Approach foregrounds relationships, emotional learning, imaginative expression, and conversation in the co-construction of knowledge. Associated models include:

- Emotionally Responsive Teaching (Emotionally Responsive Practice) (Kim Hale, 2010s) – a model of teaching that foregrounds the emotional development of learners through providing safe spaces for self-expression and responding to behaviors by validating the associated emotions

- Discovery Method (Jerome Bruner, 1960s) – a poorly defined term with a wide range of interpretations, but that was originally suggested to be a mode of teaching concerned with supporting learners in the development of knowledge and useful skills by engaging them in investigative tasks that demand sound reason and/or proper empirical work. More recent variations include:

- Divergent Discovery Teaching Style – oriented by a common topic, students are invited to structure their own engagements and to work toward satisfactory resolutions

- Guided Discovery Teaching Style – the student moves through a sequence of carefully parsed experiences designed by the teacher, ideally culminating in the realization of a predetermined concept and the honing of self-directed learning skills

- Facilitation – derived from the French faciliter “to make easy,” Facilitation is a term that is commonly used to describe attitudes and approaches to teaching associated with Embodiment Discourses. Specific interpretations vary considerably, from laissez-faire “stay out of the learner’s way” sensibilities to highly structured “deconstruct complex knowledge for learners” interventions. Most interpretations sit somewhere between, with recognized obligations to structure learning experiences and to be available to assist the learner as required.

- Facilitator Teaching Style (Self-Check Teaching Style) – a student-centered approach in which the teacher sets out the parameters and goals, but students work individually or collectively to come to an adequate outcome. In more formal versions, students are provided with explicit criteria to gauge progress and success

- Inclusion Teaching Style (Continuous Progress Teaching Style) – after being provided with an overview of a learning trajectory, the student is able to make decisions on pacing, materials, and relationship with the teacher – who is present to monitor progress and provide assistance as requested

- Looping – when a group of learners stays with the same teacher (typically, for most or all subjects) for two or more years in a row

- Mentoring – more an attitude in teaching than a mode of teaching, typically associated with strong elements of interpersonal connection, personalized feedback, and ongoing relationship

- Nondirective Teaching Model – an ill-defined, umbrella notion that has been applied to almost every approach to teaching outside our Directive Pedagogies cluster, although it appears to most often encountered in association with Personal Agency Discourses

- Platooning (Departmentalized Teaching; Distributed Teaching Model; Specialist Teaching) (early 1900s) – the practice of using specialist teachers (e.g., for reading, or mathematics) rather than generalist teachers – and having learners switch teachers for each subject (or cluster of related subjects)

- Reciprocal Teaching Style – students teaching one another, typically with the teacher available as a consultant who assigns differentiated responsibilities across students (e.g., explainers, note-takers, feedback-providers, information-gatherers)

- Reflective Teaching – more an attitude in teaching than a mode of teaching, involving knowledge of learners, theories of learning, and critical self-awareness (see Reflective Practice)

- Relationship-Centered Teaching (Relational Pedagogy; Relationship-Based Teaching; Relationship-Centered Learning) (various, 2010s) – as the title suggests, an emphasis in curriculum design and teaching on relationships. While different commentators have different foci (e.g., the teacher–student relationship, learners’ relationship to disciplines, students’ relationships with one another, humanity’s relationship with the planet), there is broad convergence around the conviction that a primary goal is a classroom ethos in which participants feel safe and able to engage critically and constructively with challenging aspects of relationships.

- Social-Inquiry Model – a teaching style that emphasizes social interaction, distinguished by the uses of formal logic and academic inquiry to resolve social issues

- Sticky Teaching (Chip Heath, Dan Heath, 2000s) – instructional approach rooted in Cognitive Science and Psychology that are intended to make learning engaging and impactful. Emphases include use of storytelling, ensuring real-world relevance, and incorporating multisensory learning.

- Teaching Presence (Terry Anderson, 2000s) – an online student-centered approach in which the teacher sets out the parameters and goals, but students work individually or collectively to come to an adequate outcome. Active interventions through collaborative computer conferencing is thought to support students engagement with the learning materials.

- Teaming (Collaborative Team Teaching; Team Teaching) – the practice of multiple teachers (typically, two to five) sharing responsibility for a larger-than-normal (typically, 50–100) students. Types of Teaming include:

- Horizontal Teaming (Horizontal Collaboration) – Teaming with a group of students at a particular grade level, in which the teaching team works together across multiple subject areas

- Vertical Teaming (Vertical Collaboration) – a continuation of Horizontal Teaming across multiple grades. (See Looping, above.)

- Whole Channel – a mode of teaching that aims to address all possible senses

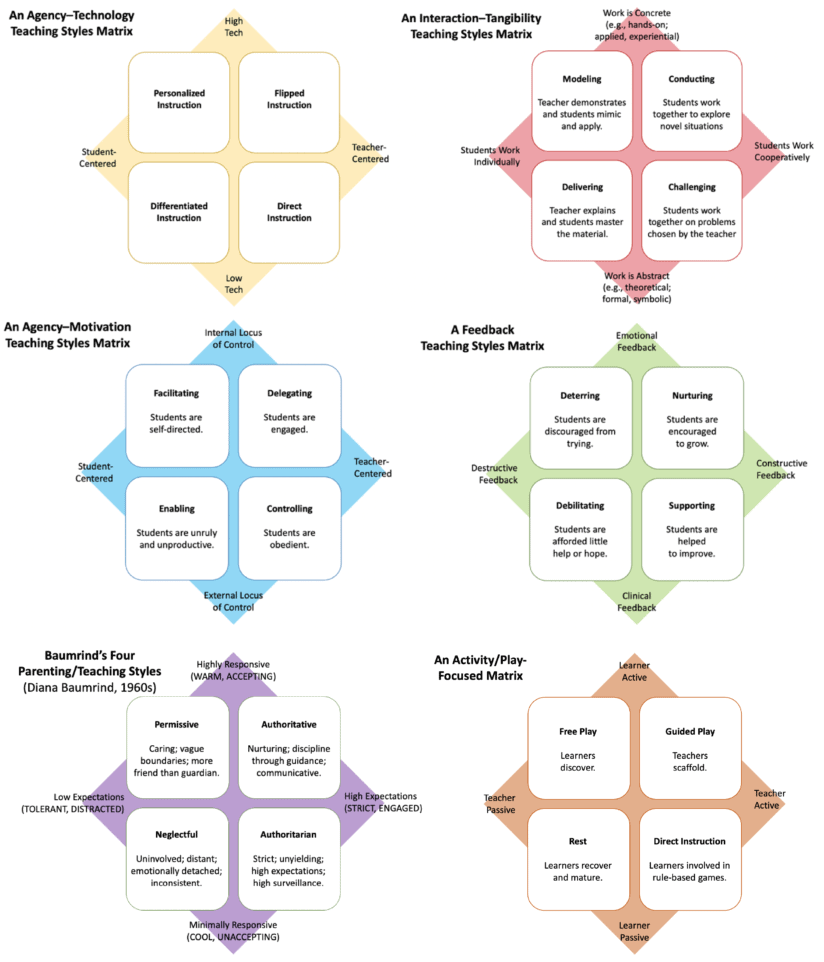

- Two-Factor Model of Teaching – any model of pedagogy that’s based on two dimensions of variation, which are used to construct a multi-cell matrix. We encountered dozens of such opinion-, survey-, or observation-based models in our scan of the literature. The following are e illustrative:

In our reviews of Teaching Styles Discourses, the above sorts of distinction-emphasizing models were rarely associated with any manner of empirical research, but nonetheless were frequently presented alongside claims on learner engagement and teacher effectiveness. In the direction of somewhat more empirically defensible and decidedly more complex examples, a few models are notable:

In our reviews of Teaching Styles Discourses, the above sorts of distinction-emphasizing models were rarely associated with any manner of empirical research, but nonetheless were frequently presented alongside claims on learner engagement and teacher effectiveness. In the direction of somewhat more empirically defensible and decidedly more complex examples, a few models are notable:

- Grasha’s Inventory of Teaching Styles (Anthony Grasha; 1990s) – a questionnaire-based model that begins by acknowledging that every teacher employs multiple styles. Based on such varied criteria as expertise, institutional authority, relationships with students, and educator intentions, Grasha identified five teaching styles: Expert, Formal Authority, Personal Model, Facilitator, Delegator. Those styles were then collected into different clusters, which were then tied to families of teaching practices that vary across such dimensions as lesson formats, assignment preferences, student participation, and learner autonomy.

- Theory of Teaching-in-Context (Teacher Model Group at UC-Berkeley, 1990s) – a model aimed at explaining and predicting teachers’ practices by defining the interactions of their beliefs, intentions, dispositions, and formal knowledge

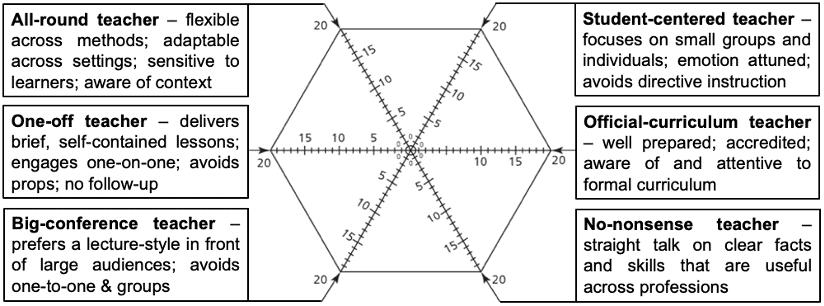

- The Staffordshire Hexagon of Teaching Styles (Kay Mohanna, Ruth Chambers, David Wall; 2000s) – a questionnaire-based model that renders scores on six scales that are then plotted on a hexagonal grid (see diagram).

Associated “styles” discourses in other activity domains

There are several other literatures that offer models on how to think about and advice for how to enact one’s responsibilities toward other’s efforts and experiences. See, e.g., Educational Management, Administration, and Leadership Discourses. Other examples include:- Parenting Styles – umbrella characterizations of parents’/caregivers’ engagements with their children, especially as those engagements are interpreted in terms of efforts or intentions to influence children’s habits of perception, social competencies, self-perceptions, attitudes toward others, and hopes for futures. Examples include:

- Authoritarian Parenting – a mode of parenting associated with distant or cool relationships, clear and rigid rules, and high expectations on children’s behavior. Variations include:

- Helicopter Parenting (Cosseting Parenting) (Haim Ginott, 1960s; rose to popular usage in early 2000s) – a mode of parenting that entails intense involvements in most, if not all, of a child’s experiences and relationships, especially in relation to schooling. In recent decades, Helicopter Parenting has become an issue in institutions of higher education, prompting many to link the phenomenon to Generational Theory.

- Concerted Cultivation (Annette Lareau, 2000s) – a mode of parenting associated with focused attention on development of language skills and social competence, typically through involvement in organized activities (e.g., sports, music, clubs)

- Monster Parenting (Yōichi Mukōyama, 2000s) – a mode of parenting associated with authoritarianism and overprotectiveness, popularized in part through discussions of the style’s negative implications for schooling

- Snowplow Parenting (2020s) – a parenting style involving active removal of obstacles or challenges from their children’s lives to ensure they experience minimal discomfort, difficulty, or failure

- Tiger Parenting (Amy Chua, 2010s) – a mode of parenting associated with pushiness and strictness, typically manifest in high expectations in academics, music, and/or sport

- Authoritative Parenting – a mode of parenting that is especially attentive to the development of values and reasoning through involved and supportive guidance within a frame of clear, sensible, and adaptable expectations. Variations include:

- Lighthouse Parenting (Kenneth Ginsburg, 2010s) – a “balanced” approach to parenting, involving both supportive guidance and measured independence – that is, in terms of the lighthouse metaphor, both reliable illumination of possible paths and freedom to self-navigate

- Punitive Parenting – the habitual use of punishment (and/or threats of punishment) to manage a child, where “punishment” is understand to include all manners of coercive practices

- Slow Parenting (Simplicity Parenting) (1990s) – associated with Slow Learning (under Alternative Education), a mode of parenting aimed at empowering children to pursue their own interests, learn at their own pace, and solve their own problems. Variations include:

- Attachment Parenting (William Sears, 2000s) – an approach to parenting that focuses on the attachment between the mother and the infant, advising steady proximity, extensive touch, and extreme responsiveness. (See Attachment Theory, under Identity Discourses.)

- Free-Range Parenting (Panda Parenting) (Lenore Skenazy, 2000s) – a mode of parenting that is associated with nurturance of independent functioning, in manners appropriate to a child’s age and developmental level

- Permissive Parenting (Diana Baumrind, 1990s) – a mode of parenting characterized by efforts to be undemanding of while affording freedom to children, oriented to nurturing agency, awareness, and judgment. The phrase Permissive Parenting is often used/heard as derogatory, as it is sometimes associated with a hands-off, abdication of parenting responsibility in helping children discern appropriate from inappropriate action.

-

Positive Parenting (Gentle Parenting; Respectful Parenting) (2010s) – a style of parenting that emphasizes regular expressions of affection, empathy, validation, kindness, and positive discipline (i.e., emphasizing positive points of behavior through clear communication and well-defined boundaries while avoiding negative discipline), which are seen both to communicate unconditional love to the child and to provide a model of how to be in the world. (See Positive Psychology.)

- Uninvolved Parenting (Neglectful Parenting; Rejecting–Neglecting Parenting) – essentially, non-parenting – that is, a mode of parenting characterized by non-responsiveness to, indifference toward, and even neglect of children’s needs

- Authoritarian Parenting – a mode of parenting associated with distant or cool relationships, clear and rigid rules, and high expectations on children’s behavior. Variations include:

- Parenting Training – an umbrella category that includes any program intended to support parents/caregivers, especially in relation to strategies for coping with and influencing problematic behaviors. Examples include:

- Parent Effectiveness Training (Thomas Gordon, 1960s) – an approach to child-rearing that relies on neither punitive discipline nor permissiveness, but on age-sensitive strategies for resolving conflicts while attending to the needs of child and parent alike

- Parent Management Training (Behavioral Parent Training) – a type of treatment program that is based on the use of Operant Conditioning techniques, used by parents to influence children’s more extreme behavior problems and disorders while supporting the development of more acceptable behaviors

Commentary

The prevailing strategies among efforts to identify Teaching Styles Discourses – that is, simple lists and simple maps – come with two intersecting problems. Firstly, such strategies can engender senses of completeness, whereas they likely omit more than they include. Secondly, in our searches, neither strategy seems to be associated with efforts to interrogate the beliefs and assumptions about learning that undergird conceptions of teaching – that is, most Teaching Styles Discourses seem to operate in complete ignorance of the fact that “learning” is a highly contested, poorly understood phenomenon and that teaching styles say at least as much about cultural norms, stakeholder expectations, institutional requirements, and professional standards as they do about personal preferences. Disconnected from critical insights into individual learning and social action, many of these discourses come across as simplistic classification schemes that say more about the observer than the observed. Against the backdrop of Teaching Styles Discourses, it is important to note that there are discourses on teaching that go in a different direction. For example, Learning Design discourses typically focus less on simple dichotomies and observable actions and more on complex dynamics and malleable attitudes.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

DiffuseStatus as a Theory of Learning

We have not encountered any Teaching Styles Discourses that could be construed as a discourse on learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Clearly, Teaching Styles Discourses are discourses about teaching. None that we encountered, however, seemed to merit the descriptor “theory,” even in very naïve senses of the word.Status as a Scientific Theory

Across all of the entries on this website, few are as laden with uncritical and unsubstantiated assumptions as this one. None of the Teaching Styles Discourses that we have been able to examine meet any of our criteria for a scientific discourse. In particular, apart from a common reliance on questionnaires that appear to be based almost entirely on beliefs, experiences, and expectations of the designers (as opposed to, for example, defensible research into learning and teaching), there appears to be little that resembles empirical evidence across these discourses. We are especially concerned with a recent trend toward deploying the notion of Best Practice in a manner similar to current uses in business contexts. These applications tend to rely on simplistic analogies between wildly different phenomena, such as student achievement on standardized tests and net profits.Subdiscourses:

- Attachment Parenting

- Authoritarian Parenting

- Authoritative Parenting

- Authority Teaching Style (Lecture Teaching Style; Command Teaching Style; Delivery Teaching Style; Direct(ing) Teaching Style; Expository Teaching; Direct Instruction)

- Balanced Instruction (Balanced Teaching)

- Baumrind’s Four Parenting/Teaching Styles

- Best Practice

- Collaborator Teaching Style (Discussing Teaching Style; Interaction Teaching Style)

- Concerted Cultivation

- Conductor Teaching Style (Hybrid Teaching Style; Blended Teaching Style)

- Delegator Teaching Style (Empowerment Teaching Style)

- Demonstrator Teaching Style (Coaching Teaching Style: Modeling Teaching Style; Practice Teaching Style)

- Developmental-Interaction Approach

- Didactic Triangle

- Didactics

- Discovery Method

- Divergent Discovery Teaching Style

- Emergent Curriculum

- Emotionally Responsive Teaching (Emotionally Responsive Practice)

- Facilitation

- Facilitator Teaching Style (Self-Check Teaching Style)

- Fixed/Mandated/Imposed Curriculum

- Free-Range Parenting (Panda Parenting)

- Grasha’s Inventory of Teaching Styles

- Guided Discovery Teaching Style

- Helicopter Parenting (Cosseting Parenting)

- Horizontal Teaming (Horizontal Collaboration)

- Inclusion Teaching Style (Continuous Progress Teaching Style)

- Lighthouse Parenting

- Looping

- Mentoring

- Monster Parenting

- Nondirective Teaching Model

- Parent Effectiveness Training

- Parent Management Training (Behavioral Parent Training)

- Parenting Styles

- Parenting Training

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK)

- Permissive Parenting

- Platooning (Departmentalized Teaching; Distributed Teaching Model; Specialist Teaching)

- Positive Parenting (Gentle Parenting; Respectful Parenting)

- Punitive Parenting

- Reciprocal Teaching Style

- Reflective Teaching

- Relationship-Centered Teaching (Relational Pedagogy; Relationship-Based Teaching; Relationship-Centered Learning)

- Signature Pedagogies

- Slow Parenting (Simplicity Parenting)

- Snowplow Parenting

- Social-Inquiry Model

- Staffordshire Hexagon of Teaching Styles

- Sticky Teaching

- Structured Learning

- Student-Centered Learning (Child-Centered Learning; Learner-Centered Education)

- Teacher-Centered Learning (Instructor-Centered Learning)

- Teacher Cognition

- Teaching to the Middle

- Teaching Presence

- Teaming (Collaborative Team Teaching; Team Teaching)

- Theory of Teaching-in-Context

- Tiger Parenting

- TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge; Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge)

- Two-Factor Model of Teaching

- Uninvolved Parenting (Neglectful Parenting; Rejecting–Neglecting Parenting)

- Unstructured Learning

- Vertical Teaming (Vertical Collaboration)

- Whole Channel

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Teaching Styles Discourses” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List