Focus

Exploiting habits of perception to support conceptual learningPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … evolving webs of coherent interpretations

- Knowing is … acting and interpreting (based on one’s history)

- Learner is … a noticer and integrator (individual)

- Learning is … construing, connecting, interpreting, weaving

- Teaching is … challenging attentions and juxtaposing critical features

Originated

1990sSynopsis

Variation Theory is based on four key principles from Cognitive Science, namely that (1) the capacity of working memory is very limited, (2) every experience presents innumerable features that might consume one’s attention, (3) established collective knowledge tends to be well structured and reliant on highly specific “critical features,” and (4) humans are exquisitely attuned to change/difference. Variation Theory thus offers focused advice on supporting robust conceptual development through strategies for structuring tasks to make specific noticings available, for channeling learners’ limited attentions to critical features (e.g., systematic variation of the critical feature while holding all other features constant), and for supporting learners in making appropriate generalizations. Important principles of Variation Theory include:- “Differences that make a difference” (“Differences which make a difference”) (Gregory Bateson, 1970s) – a definition of “information” – that is, those variations in one’s world that register as consequential

- Principle of Difference (Ference Marton, 2010s) – the noticing of a specific aspect of an object of learning is greatly enabled by encountering variations of that aspect against a backdrop of constancy

- Isolation Effect (Von Restorff Effect) (Hedwig von Restorff, 1930s) – the observation that an item that stands out from its surroundings (e.g., a red ball among many blue ones) is more likely to be remembered than other items

- Adaptation-Level Theory (Harry Helson, 1940s) – the principle that noticings and assessments of qualities are situationally dependent – so that, for example, a crying baby might be judged as “noisy” while the much louder background sound of airplane engines goes unnoticed, or a particular pen might be perceived as heavy while a much much heavier brick is perceived as light. Thus, levels of stimulation might have to be adapted to be noticed.

- Differentiation Theory of Perceptual Development (Eleanor Gibson, 1960s) – a theory of perception that describes it as an iteratively developed screening process, by which one learns to filter “noise” (i.e., distracting and non-useful information) while discerning essential characteristics of the experience

- Theory of Collative Properties (Daniel Berlyne, 1960s) – the hypothesis that one’s responses to environmental stimuli – that is, one’s levels of arousal or noticing – are indexed to qualities that prompt “perceptual conflict” with other events. Four main attributes, which can operate separately on in combination, are identified: complexity, novelty, incongruity, surprisingness.

- Recognition-by-Components Theory (RBC Theory) (Irving Biederman, 1980s) – a model of perception and recognition that is structured around the separation, noticing, and recombining of distinctive-and-necessary elements of objects (labeled “geons”)

- Theory of Instruction (Direct Instruction) (Siegfried Engelmann, Douglas Carnine, 1980s) – a model of instruction rooted in two convictions about learning: (1) one can learn about any specific feature through appropriate examples; (2) one can develop conceptual understandings by generalizing common features across sets of appropriate examples (Note that the meaning of Direct Instruction associated with this theory is distinct from most popular uses of the term – as described in Teaching Styles Discourses. In this theory, “directing” is about orienting attentions, not transferring of information.)

- Intelligent Practice (Craig Barton, 2020s) – exercise sequences that are structured in a manner intended to prompt attentions to relationships, patterns, properties, or other critical discernments

Commentary

Relative to other educational theories, Variation Theory has a very narrow focus. For that reason, it tends to assume rather than assert key principles of learning – for example, the tenet that what one learns is principally conditioned by both what one already knows and what one is currently noticing. (Other examples are shared with various Embodiment Discourses). Variation Theory’s advice on channeling learner attentions is theoretically sound and empirically grounded. However, that advice is only useful if accompanied by rather sophisticated knowledge of the structures of concepts under study. It’s one thing to prompt awareness to critical features, and it’s quite another to do so in sequences that support sound construals.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Ference MartonStatus as a Theory of Learning

Proponents of Variation Theory often assert that it is both a theory of learning and a theory of teaching, given that it is grounded in principles of Cognitive Science and that it offers pragmatic advice for educators. Because it does not develop or extend insights into the complex dynamics of learning, we do not classify it here as a theory of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

In our analysis, Variation Theory is principally a theory of teaching.Status as a Scientific Theory

Variation Theory is gaining a strong foothold in some areas of educational research, particularly those associated with the STEM domains. Emerging results, coupled to its solid theoretical grounding, appear sufficient to assert that Variation Theory is a scientific theory.Subdiscourses:

- Adaptation-Level Theory

- “Differences that make a difference” (“Differences which make a difference”)

- Differentiation Theory of Perceptual Development

- Intelligent Practice

- Isolation Effect (Von Restorff Effect)

- Principle of Difference

- Recognition-by-Components Theory (RBC Theory)

- Theory of Collative Properties

- Theory of Instruction (Direct Instruction)

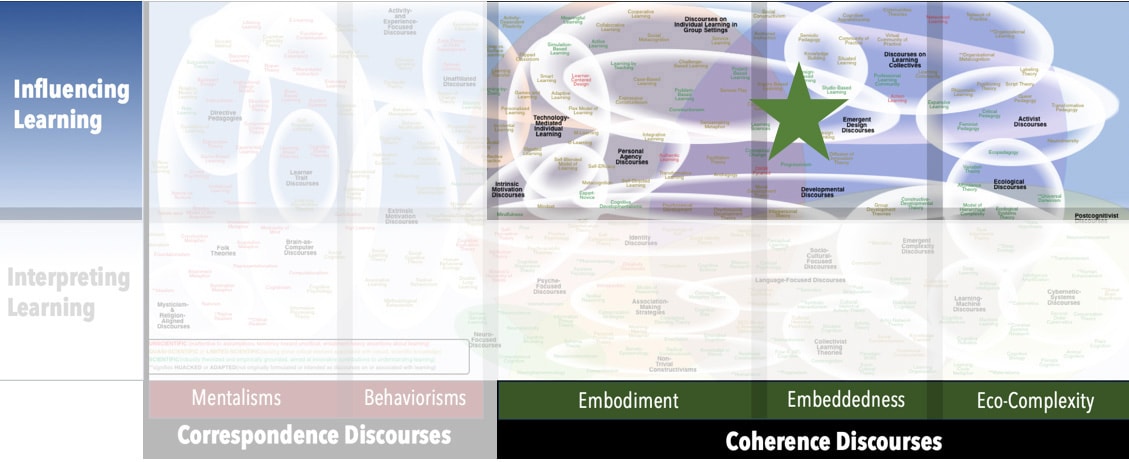

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Variation Theory” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List