AKA

Categorical Learning

Categorization Styles

Category Learning

within a Focus

Strategies used to recognize, differentiate, associate, and understand ideas and objectsPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … array of useful categories

- Knowing is … appropriate categorization

- Learner is … a categorizer

- Learning is … developing categories

- Teaching is … signaling differences and associations

Originated

Varied, but there was a surge in the 1950sSynopsis

Discourses on Categorization Strategies focus on the processes used to recognize, differentiate, associate, and understand ideas and objects. Several strategies have been identified, and all appear to be strongly associated with cultural influences (i.e., personal preferences for specific modes are likely dependent on one’s situation). Associated constructs and theories include:- Basic-Level Category (Basic Category; Natural Category) – a category that sits/operates at a level that feels natural and common-sensical. That is, a Basic-Level Category impart of an organizational hierarchy (unlike an Ad Hoc Category, below) that feels neither too narrow for everyday thought (see Subordinate Category, below) nor too broad for most purposes (see Superordinate Category, below):

- Ad Hoc Category – a temporary category created for a specific purpose in relation to a specific moment/activity (e.g., “foods that are easy to eat while driving”)

- Subordinate Category – a narrower, more-focused subset of a Basic-Level Category (e.g., “poodles” vs. “dogs”), in which distinctions among members are more fine-grained than necessary for most people at most times.

- Superordinate Category – a broad, high-level category that includes multiple Basic-Level Categories (e.g., “mammals” vs. “dogs”), in which differences among members are typically so significant that the category is not especially useful for most people at most times

- Categorical Perception – the influence on perception of distinct categories of phenomena. These categories influence what is perceived as similar and as different. (E.g., the “p” sound in hop is slightly different to the sound in pit, spa, and hoop – a point that is represented in some written languages through the use of distinct symbols. In English, however, they’re typically perceived as the same and few speakers can readily hear the differences.)

- Categorical Thought (Abstract Thinking) (Jean Piaget, 1950s) – a mode of thinking involving the uses of generalized ideas, concepts, or classifications

- Categories of Thought (Immanuel Kant, 1770s) – a list of fundamental concepts that are suggested to be necessary to human understanding of material objects and physical experience (i.e., to derive meaning from sensory information). Kant proposed 12 Categories of Thought, which can be clustered into four groups: Quantity (Unity, Plurality, Totality); Quality (Reality, Negation, Limitation); Relation (Substance and Accident, Cause and Effect, Reciprocity); Modality (Possibility, Existence, Necessity)

- Classical Categorization (Categorical Classification; Nominal Classification; Similarity Classification; Taxonomic Classification) (ancient Greeks, 4th century BCE) – focuses on similar and different properties (e.g., birds have feathers, lay eggs, have beaks, etc.), and it is often associated with rule-based strategies for assigning ideas and objects to groups. This approach is foundational to many Modes of Reasoning, especially deductive logic.

- Exemplar Theory (Instance Theory) (D.L. Hintzman, G. Ludlam, 1980s) relies on specific instances, whereby an actual member of a category is used as the basis to determine whether other instances belong.

- Family Resemblance (Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1950s) – a mode of categorizing in which there is no essential feature that is common to all members of the category. Rather, each member need have only a few qualities in common with other members. Those members that have the most in common with the most members are sad to have the greatest “family resemblance.”

- Narrative-Based Clustering (Alexander Luria, 1950s) relies on personal experiences and pragmatic uses to categorize.

- Prototype Theory (Eleanor Rosch, Brent Berlin, Paul Kay, 1970s) relies on generalized, abstract “average” (e.g., robins and starlings are more prototypical birds than ostriches and penguins). Associated constructs include:

- Typicality Effect (Eleanor Rosch, 1970s) – the observation that “typical” members of a category are learned earlier and more easily than “atypical” items, since they provide more accessible information on the qualities or traits that define the category

Commentary

At least since the Enlightenment, it has been assumed that the capacity for formal, deductive logic is what definitively separates humanity from non-human species. A corollary of that assumption is that humans are logical beings – which, on closer examination, is demonstrably false. Discourses on Categorization Strategies have provided some important insight into the multiple (often non-logical) ways that humans parse their worlds, affording more varied and nuanced insights into how learning happens.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Diffuse, but Jean Piaget was a major influenceStatus as a Theory of Learning

Discourses on Categorization Strategies provide important insights into how humans learn. That is, while it would be a stretch to describe them of theories of learning, they are integral to understanding learning – and, typically, are explicitly incorporated into contemporary scientific learning theories.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Discourses on Categorization Strategies are not theories of teaching.Status as a Scientific Theory

Discourses associated with Categorization Strategies have been extensively researched and fulfill all our criteria for scientific theories.Subdiscourses:

- Ad Hoc Category

- Basic-Level Category (Basic Category; Natural Category)

- Classical Categorization (Categorical Classification; Nominal Classification; Similarity Classification; Taxonomic Classification)

- Categorical Perception

- Abstract Thinking (Categorical Thought)

- Categories of Thought

- Exemplar Theory (Instance Theory)

- Family Resemblance

- Narrative-Based Clustering

- Prototype Theory

- Subordinate Category

- Superordinate Category

- Typicality Effect

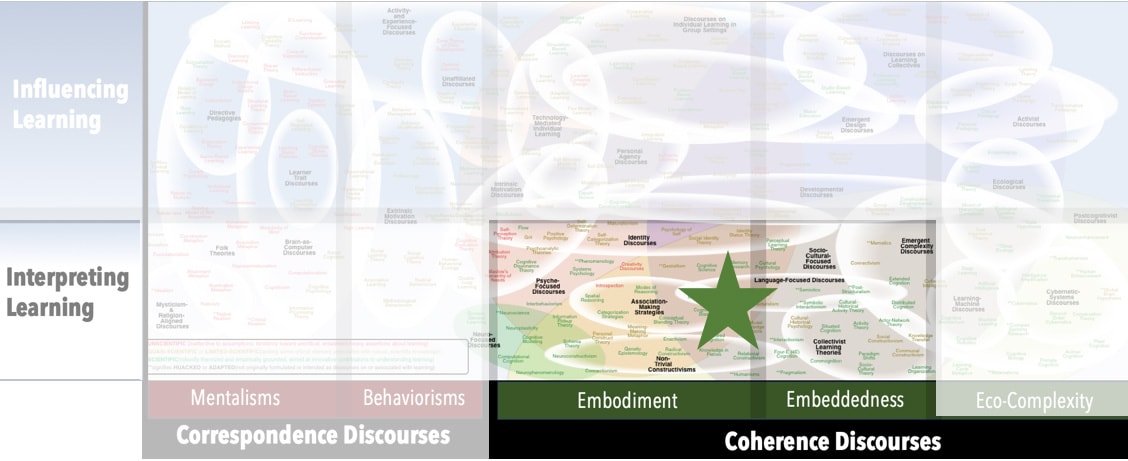

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Categorization Strategies” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List