Focus

Strategies used to derive or validate insights based on established insightsPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … scope of possible interpretation

- Knowing is … considered thought and action

- Learner is … a thinker (individual)

- Learning is … reasoning

- Teaching is … challenging (to think)

Originated

Ancient (entrenched in the language)Synopsis

Modes of Reasoning refers to a range of conscious processes used to derive and/or validate assertions based on established understandings:- Reason (Ratiocination; Rational Thinking) – most broadly conceived, any systematic means to interpret a situation or draw a conclusion. More narrowly, and reflecting its shared roots with the word “rational,” Reason is often used narrowly as a reference to the formal logical argument.

- Dianoia (Plato, 300s BCE) – modes of reasoning associated with mathematical and technical processes, especially Logic and Deductive Reasoning (see below)

- Noesis (Plato, 300s BCE) – reasoning rooted in a wealth of experience, including Inductive Reasoning, Analogical Reasoning, and most other non-logico-deductive Modes of Reasoning listed below.

- Paradigmatic Mode (Paradigmatic Mode of Thinking) (Jerome Bruner, 1960s) – a mode of knowing oriented toward and by the development of laws, predictive models, theories, concepts, and categories

- Narrative Mode (Narrative Mode of Thinking) (Jerome Bruner, 1960s) – a mode of knowing that relies on story-crafting and story-telling to enable the teller to render coherence from their particular and perhaps-anomalous experiences

- Analysis (Analytic Thinking; Analytical Thinking; Analytic Approach) – any method of reasoning or investigation that involves breaking down a phenomenon into fundamental aspects. Analytic Thinking assumes that the whole is the sum of its parts, and so it is best suited to logical and mechanical systems that can be reduced to their components. The term traces back to the Greek analusis “dissolving."

- Synthetic Thinking (Synthetic Approach; Systemic Approach; Systemic Thinking) – any method of reasoning or investigation that involves the blending or merging of various aspects into a more complex whole. Synthetic Thinking assumes that the functional possibilities of the whole can exceed the sum of the possibilities of the individual components.

- Deductive Reasoning (Deductive Logic; Logical Deduction; Top-Down Logic) – a formal process of moving from premises to a logically certain conclusion. Specific rules apply. Associated constructs include:

- Conditional Reasoning (If–Then Reasoning; Inferential Reasoning) – a mode of reasoning that moves from explicit premise to sensible inference (e.g., If my printer stops working, then it must be out of toner.)

- Logic – formally: the study and application of systems of rules used to assess the validity of conclusions that are based on sets of initial propositions. (See Rationalism for a list of some types of Logic.)

- Inductive Reasoning (Bottom-Up Logic) – making generalizations on the basis of specific examples. It occurs when, based on a pattern of events or premises, one anticipates future events or implications. Inductive Reasoning has to do more with expectation than certainty. Specific types of Inductive Reasoning include:

- Categorical Thought (Abstract Thinking) (Jean Piaget, 1950s) – a mode of thinking involving the uses of generalized ideas, concepts, or classifications

- Abductive Reasoning (Abduction; Abductive Inference; Case-Based Reasoning; Retroduction) – an explanation-oriented mode of reasoning that moves backward from facts/events to plausible explanations of those facts/events. It is concerned with reasonableness rather than certainty, and it might be described in terms of seeking simple and likely explanations. Specific types of Abductive Reasoning include:

- Analogical Reasoning (Analogy) – an interpretation strategy that involves drawing (figurative) associations between a familiar phenomenon (the analog, source, or source domain) and a new phenomenon (the target, or target domain). Specific types of Analogical Reasoning include analogies, metaphors, similes, allegories, parables, and exemplification. (See Conceptual Metaphor Theory.)

- Deductive Reasoning version: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore Socrates is mortal.

- Inductive Reasoning variation (i.e., reasoning from a specific example): Socrates is a man. Socrates is mortal. Therefore all men are mortal.

- Abductive Reasoning variation (i.e., reasoning by association): All men are mortal. Socrates is mortal. Therefore Socrates is a man.

- Bounded Rationality – associated with Pragmatism, and about making good-enough (vs. optimal) decisions, taking into account such constraints as time pressures, problem complexity, resource availability, and cognitive limitations.

- Commonsense Reasoning – highlighted by research into Artificial Intelligence, Commonsense Reasoning spans the fluid, flexible, but hard-to-mimic abilities to derive meaning, infer intention, and anticipate possibilities within complex situations, based on lifetimes of experiences using cultural tools to make sense of the physical world with others

- Dialectical Reasoning (Dialectics) (Johann Fichte, 1790s) – a Mode of Reasoning that starts with a formal statement of the point (thesis), followed by a contradiction of negation of that point (antithesis), and ends in a coherent resolution (synthesis)

- Genealogy (Friedrich Nietzsche, 1930s) – a historical technique that rejects linear narratives and causal logic (contrast, e.g., Great Man Theory of History, under Paradigm Shifts), attempting instead to consider the ranges of social and political influences during the time under study. Related notions include:

- Bifurcation (Brent Davis, 2000s) – a historical technique that rejects Dichotomous Thinking (see below) and focuses instead on the conceptual origins of commonly invoked dyads (e.g., “hot v cold” might be linked in the notion of “temperature ranges tolerated by humans”). The word Bifurcation is from the Latin bi- + furca “two forks.” It was chosen because the two prongs of a bifurcated fork come together to point to their common root.

- Moral Reasoning – any process by which one attempts to determine proper courses or action and/or to distinguish been “right” and “wrong,” typically by using some manner of Conditional Reasoning, Inductive Reasoning, or Analogical Reasoning.

- Paradoxical Thinking (Both/And Thinking) – considering and embracing contradictions or opposing viewpoints to understand complex situations. Used deliberately, Paradoxical Thinking can be effective for reframing problems and supporting creative thinking. Less deliberate manifestations of Paradoxical Thinking are sometimes indicators of psychological disorders, especially if accompanied by other thought processes that are not well fitted to the context. Reasonably prominent examples of Paradoxical Thinking in education include:

- Choice Paradox (Paradox of Choice) – the more choices one has, the less likely one is to be content with one’s decision

- Desire Paradox – the observation that that the more one desires something, the less likely one is to achieve true fulfillment … even if that desire is met

- Effort Paradox – the counterintuitive phenomenon where increasing effort does not necessarily lead to improved performance or outcomes – and in some cases, it can even lead to worse results

- Failure Paradox – the observation that failure leads to success by offering valuable lessons, fostering growth, resilience, and innovation

- Growth Paradox – variously interpreted – e.g., (1) the suggestion that growth often involves discomfort and struggle, yet these challenges are essential for personal development, or (2) the idea that growth can occur both suddenly and gradually, with unpredictable patterns

- Learning Paradox (Plato, c. 400 BCE) – the assertion that learning is inherently impossible, arising from the assumption that one can only recognize a phenomenon on the basis of what one already knows

- [Law of] Parsimony (Economy Principle; Epistemic Simplicity; Principle of Economy; Principle of Parsimony) – based on a metaphor of frugality (i.e., the intended meaning of both parsimony and economy in this case), the suggestion that the simplest explanation of a phenomenon is the desirable explanation. While not technically a Mode of Reasoning, the Law of Parsimony is embraced across most defensible modes. Associated notions include:

- Elegant Solution – the solution to a problem that leads to the desired result with minimum conception effort and material requirements

- Occam’s Razor (William of Occam, early 1300s) – the principle that, when presented with multiple plausible explanations for a phenomenon, the simplest one (i.e., with the fewest assumptions, concepts, etc.) is the preferred one

- Practical Reason (Practical Rationality) – a term that reaches across all modes of engaging systematically with novel questions and problems in everyday life. The “practical” of the term refers to both pragmatic focus and action orientation.

- Instrumental Rationality – an aspect of Practical Reason that is focused on means and ends – specifically, the efficient use of available resources to attain desires

- Consequentialism – any perspective on knowledge, behavior, and/or morality founded on the principle that rightness or wrongness of one’s actions is determined by the consequences of those actions. That is, it is the outcome that counts, not the intention. (Contrast: Intentionalism, below.)

- Value Rationality – an aspect of Practical Reason that is focused on one’s motivations for acting, whether noble or not. That is, the desired outcome is a factor in one’s decisions, but the actual outcome is immaterial.

- Intentionalism – any perspective on knowledge, behavior, and/or morality founded on the principle that rightness or wrongness of one’s actions is seen to reside in one’s intentions. (Contrast: Consequentialism, above. Note: This meaning of Intentionalism is different from the one used in Psychology, where the term is sometimes used as an alternative name for ACT Psychology.)

- Instrumental Rationality – an aspect of Practical Reason that is focused on means and ends – specifically, the efficient use of available resources to attain desires

- Pragmatic Reasoning Schema Theory (Patricia Cheng, Keith Holyak, 1980s) – a model of Conditional Reasoning (see above) that spells out implicit and situation-specific rules of inference that are rooted in experience – whereby situations triggers rules, which become bases for reasoning

- Probabilistic Thinking – based on an assumption that the universe obeys the laws of probability, Probabilistic Thinking is a model of reasoning and decision-making that involves calculating (or reasonably estimating) the likelihoods of identified outcomes to specific actions. Ironically, proponents of Probabilistic Thinking generally concede that, even among the small portion of people capable of calculating (or reasonably estimating) probabilities, just a tiny subset is able to act on those results.

- Scientific Reasoning – a mode of reasoning that includes clearly specifying a problem, developing hypotheses, and conducting replicable tests of those hypotheses

- Fuzzy Trace Theory (Charles Brainerd, Valerie Reyna, 1990s) – a theory that attempts to account for observed anomalies in memory and reasoning with the suggestion that humans create two types of mental representations for past experiences: fuzzy ones and precise ones. Relying exclusively on one or the other can give rise to tensions or inconsistencies with reasoned action.

- Polylogism (Ludwig von Mises, 1990s) – a recognition that preferred or privileged Modes of Reasoning may vary from one sociocultural group to another – depending on, for example, era, rates of literacy, levels of education, and prominence of religion

Commentary

The biggest issue with Modes of Reasoning is that they are notoriously difficult to study – since, to do so, they need to be applied to themselves. A simple fact that should give pause is it has only been recently that humanity has realized that what most defines our thinking capacities is not Deductive Reasoning (which is trivial with computers), but Analogical Reasoning (which is notoriously difficult to simulate). That development might be taken as an indication that there is still much to learn about how humans think. In addition, the backdrop of all of the above is the realization that human thinking is a far-from-unified phenomenon. In that regard, many ways to undermine or avoid coherent Modes of Reasoning have been studied, some of which are described in the Cognitive Bias entry. Others types and techniques of problematical reasoning include:- Non-Deliberate Inclinations

- Allusive Thinking (Cognitive Looseness; Loose Associative Processing) – contriving “meaningful” and resilient associations among random or unrelated events, thus potentially confounding oneself and bewildering acquaintances

- Delusion – a fixed, false belief resistant to evidence or reason, often seen in psychiatric disorders. A Delusion is not culturally endorsed, and it persists despite contradiction. Emerging evidence suggests that Delusions are not primarily “logical errors”; rather, they likely have emotional roots.

- Dichotomous Thinking (Black-and-White Thinking; Dualistic Thinking; Polarized Thinking) – framing a thought or argument in terms of two non-overlapping categories or extreme opposites (i.e., rejecting alternative frames, shades of grey, or middle positions)

- Double Bind (Gregory Bateson, 1950s) – a dilemma involving incompatible messages, whereby an agent is faced with two irreconcilable demands or two unwanted options

- Doublethink (George Orwell, 1940s) – Orwell introduced the term Doublethink in the book 1984 to refer to one’s ability manage memories by choosing what to forget. The word has come to refer to one’s ability to hold contradictory beliefs at the same time, even when one or both of those beliefs might be at odds with one’s experience.

- Idée Fixe (Fixed Belief; Fixed Idea) – a Delusion, Fallacy, or other conviction that is rigidly held despite evidence to the contrary

- Irrationality – literally, the “absence of rationality/reason” – which, as might be inferred from the many Modes of Reasoning listed above, is a problematic construct because it relies on (usually unstated) assumptions of what might constitute acceptable reasoning in a given context

- Mind Traps (Cognitive Distortions; Negative Automatic Thoughts; Thinking Errors; Thinking Traps; Thought Traps; Unhelpful Thoughts) – an umbrella category of non-rational and typically obsessive thoughts that can negatively channel attentions, impact emotions, tip decisions, and trigger actions

- Motivated Reasoning Theory (Motivational Reasoning Bias) – the suggestion that one’s choice among Modes of Reasoning in a specific situation is affected by one’s intentions, motivations, emotional mindset, belief system, and other non-rational influences

- Paralogism – a fallacy or flawed argument. The term is most often applied to those that are nondeliberate and subtle.

- Scientism – an uncritical and/or exaggerated trust in the science as the best or only route to unimpeachable fact

- Two-Plus-Two Phenomenon – the unjustified leap from observed events and/or unquestioned assumptions to a certain conclusion, with no critical questioning or logical analysis. The name is an implicit analogy to the obviousness and certainty of “2 + 2 = 4”.

- Deliberately Deceptive and/or Manipulative Tactics

- Loaded Language (Emotive Language; High-Inference Language; language-Persuasive Techniques; Loaded Terms) (Charles Stevenson, 1930s) – vocabulary and phrasing intended to appeal to emotion rather than reason, such as “regime” instead of “leadership,” or “lecturing” instead of “explaining”

- Obscurantism – a conscious opposition to reasoned argument, often rooted in a desire to preserve religious, political, or cultural convictions

- Pseudoskepticism (Henri-Frédéric Amiel, 1860s) – the practice of claiming to be skeptical or critical of certain ideas or claims, but actually using flawed reasoning or illogical arguments to dismiss them without genuinely engaging with the evidence

- Thought-Terminating Cliché (Bumper-Sticker Logic; Cliché Thinking; Semantic Stop Sign; Thought-Stopper) (Robert Jay Lifton, 1960s) – a brief, familiar statement that is deployed to end terminate discussion or debate, such as “Let’s agree to disagree” or “It is what it is.”

- Fallacious Reasoning (Fallacy; Fallacious Argument; Logical Fallacy; Rhetological Fallacy; Specious Reasoning) – basing an argument on an error or a false move, thus giving a ring of truth when it is actually unsupported. Many dozens of types of Fallacious Reasoning have been catalogued. (Note: Fallacious Reasoning is often confused with, but is distinct from, Cognitive Bias, which is about nondeliberate patterns of interpretation, such as errors of perception, habits of association, and uncritical generalizations. Click here for a reasonably comprehensive taxonomy.) Prominent types include:

- Ad Hominem – Latin for “to the person,” a type of Fallacious Reasoning that involves attacking of the person making an argument, rather than taking on the actual argument

- Appeal to Authority - a type of Fallacious Reasoning that asserts an argument must be true because it is associated with an expert or powerbroker

- Appeal to Ignorance – a type of Fallacious Reasoning in which either an argument is asserted false if it can’t be proven true or an argument is asserted true if it can’t be proven false

- Appeal to Tradition – a type of Fallacious Reasoning by which a detail is taken to be true by virtue of having been assumed for a long time

- Bandwagon – a type of Fallacious Reasoning based on a conflation of popularity and factuality

- Circular Reasoning – a type of Fallacious Reasoning in which the conclusion is actually just a rephrasing of an initial assumption

- False Analogy – a type of Fallacious Reasoning in which a noticed similarity between two phenomena leads to a troublesome conclusion that those phenomena must be similar in other ways (This website is rife with examples. Because virtually every discourse presented is grounded in specific metaphors/analogies, all of them present the risk of over-extending those metaphors into False Analogies.)

- False Dichotomy (False Dilemma)– a type of Fallacious Reasoning in which two choices (usually opposites) are presented as the only possible choices, even though other options are possible

- Hasty Generalization – a type of Fallacious Reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn on an unjustifiably small number of occurrences

- Red Herring – a type of Fallacious Reasoning by which a conclusion is compromised by diverting the focus and/or the argument to irrelevant matters

- Slippery Slope – a type of Fallacious Reasoning that involves one or more dubious assumptions that are likely to seriously undermine any conclusion

- Straw Man – a type of Fallacious Reasoning that involves criticizing an irrelevant aspect or a distorted version of an argument

- Ignorance Studies (various, 2020s) – an emergent, cross-disciplinary domain that pulls together theoretical and empirical studies of ignorance from across education, law, politics, science, and other areas. Some associated constructs and discourses are listed below. See also Conscious Competence Model of Learning.

- Ignorance (1300s) – a lack of knowledge or awareness. Ignorance originally meant “opposite of knowing” (combining Latin prefix in- and PIE root *gno-). The current pejorative associations to being ill-mannered and/or deliberately uninformed arose in the late 1800s. Associated constructs include:

- Willful Ignorance – the deliberate dismissal of and/or refusal to acknowledge available information and/or sound reasoning – typically in order to avoid an undesired conclusion and/or to maintain an existing belief

- Agnosticism (Thomas Henry Huxley, 1860s) – based on a Greek word meaning “unknown or unknowable” (combining Greek prefix a- and PIE root *gno-), an English word originally coined to signal the importance of “scientific grounds” to any claim to truth. It has since evolved to refer to topics and situations in which knowers’ conviction is “We cannot know”(i.e., unknowability) – versus “We do not know” (i.e., the unknown).

- Agnotology (Agnatology) (Rober Proctor, 1990s) – the study of cultural ignorance or the deliberate creation and spread of ignorance, often by powerful groups or institutions, to shape public perception, policy, or behavior

- Inoculation Theory (William McGuire, 1960s) – a perspective on how people can be preemptively “immunized” against ignorance, persuasion, or misinformation by being exposed to weakened versions of counterarguments before encountering full-fledged attempts to change their beliefs

- Naturalistic Fallacy – a logical error, most often encountered in moral arguments, that is due to the assumption a value (e.g., “goodness”) has a real, tangible existence

- Red Pill and Blue Pill (popularized by The Matrix, 1990s) – a metaphor that represents a choice between accepting and uncomfortable truth or remaining in comfortable ignorance

- Skepticism – an umbrella notion applied to an array of discourses that, to varying extents, question the possibility of factual knowledge. Positions range from advice to suspend judgment to denying the very possibility of knowledge. Types of Skepticism vary according to scope, method, and associated philosophy.

- Ignorance (1300s) – a lack of knowledge or awareness. Ignorance originally meant “opposite of knowing” (combining Latin prefix in- and PIE root *gno-). The current pejorative associations to being ill-mannered and/or deliberately uninformed arose in the late 1800s. Associated constructs include:

- Science Denialism (Denialism) – the rejection or distortion of well-established scientific facts, theories, or findings, often despite overwhelming evidence supporting them. Science Denialism involves the deliberate dismissal or misrepresentation of scientific knowledge, often driven by ideological, political, economic, or personal interests rather than evidence or reasoned argument. Types and techniques include:

- Cherry Picking – highlighting specific pieces of data that support a desired conclusion while ignoring contradictory evidence

- Anecdote – a personal story or individual experience that is used as evidence to support a claim or argument, even though such individual cases do not provide reliable or representative data

- Quote Mining – the practice of selectively excerpting a statement or quotation from a larger context in order to misrepresent or distort its original meaning

- Slothful Induction – the failure to make a reasonable inference or to draw a defensible conclusion, despite having sufficient and clear supporting evidence

- Conspiracy Theory – a belief or explanation that suggests events or situations are the result of a secret, often sinister, plot by a group of people or organizations, rather than being caused by more plausible, observable, or rational factors. These theories often rely on the idea that the truth is being hidden from the public and that the official accounts of events are deceptive or false.

- Contradictory – presenting conflicting or inconsistent claims, often to make it seem like there’s a hidden truth being covered up, even though the contradictions undermine the credibility of the theory itself

- Immune to Evidence – rejecting any evidence that contradicts the conspiracy theory, even when presented with strong, peer-reviewed data

- Nefarious Intent – the attribution of malicious, often secretive, motives to individuals or groups, suggesting they are intentionally deceiving or harming others for personal gain

- Overriding Suspicion – the application of deep, pervasive mistrust to any information that contradicts the conspiracy, regardless of its credibility, often leading to constant doubt

- Persecuted Victim – portraying the individual or group promoting the conspiracy as a victim of widespread persecution or suppression, often to garner sympathy and justify their beliefs

- Re-Interpreting Randomness (Attributing Causality to Coincidence) – interpreting random events or coincidences as evidence of a coordinated conspiracy, often leading to improbable conclusions based on very little or no evidence

- Something Must Be Wrong – the assumption that, if something is difficult to understand or appears complicated, it must be a deliberate attempt to conceal the truth

- Fake Experts – persons who are presented as having authority or expertise on a particular subject, but whose qualifications, knowledge, or experience do not genuinely support their claims

- Bulk Fake Experts – gathering a large number of people who, although presented as experts, are often not qualified or their qualifications are irrelevant to the specific issue at hand

- Fake Debate - the illusion of a robust debate where there is actually very little disagreement within the scientific community. It is typically accomplished by pitting a small (and often unqualified) group of dissenting voices against the vast majority of experts.

- Magnified Minority – a small group of experts who dissent from the mainstream scientific consensus. These experts are often given disproportionate attention or elevated as representing a credible opposition, even though their views do not reflect the majority of experts.

- Impossible Expectations – imposing unrealistic or unattainable standards of evidence before accepting a scientific conclusion

- Moving Goalposts – shifting the criteria for acceptable evidence so that no amount of proof is ever sufficient to meet the adjusted standard

- Cherry Picking – highlighting specific pieces of data that support a desired conclusion while ignoring contradictory evidence

- Bullshit Asymmetry Principle (Brandolini's Law; BS Asymmetry Principle) (Alberto Brandolini, 2010s) – a commentary on the frustrating nature of misinformation, propaganda, and pseudoscience: "The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude larger than to produce it."

Authors and/or Prominent Influences

DiffuseStatus as a Theory of Learning

Modes of Reasoning are properly understood as theories of learning. Each is a mode of generating and/or confirming new understandings – which is an interpretation of “learning” that fits across most discourses.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Modes of Reasoning do not constitute a theory of teaching.Status as a Scientific Theory

Modes of Reasoning are associated with extensive philosophical and empirical research.Subdiscourses:

- Abductive Reasoning (Abduction; Abductive Inference; Case-Cased Reasoning; Retroduction)

- Abstract Thinking (Categorical Thought)

- Ad Hominem

- Agnosticism

- Agnotology (Agnatology)

- Allusive Thinking (Cognitive Looseness; Loose Associative Processing)

- Analogical Reasoning

- Analysis (Analytic Approach; Analytic Thinking; Analytical Thinking)

- Anecdote (in Denialism)

- Appeal to Authority

- Appeal to Ignorance

- Appeal to Tradition

- Bandwagon

- Bifurcation

- Bounded Rationality

- Bulk Fake Experts

- Bullshit Asymmetry Principle (Brandolini’s Law; BS Asymmetry Principle)

- Cherry Picking

- Choice Paradox (Paradox of Choice)

- Circular Reasoning

- Commonsense Reasoning

- Conditional Reasoning (If–Then Reasoning; Inferential Reasoning)

- Consequentialism

- Conspiracy Theory

- Contradictory (in Denialism)

- Deductive Reasoning

- Delusion

- Desire Paradox

- Dialectical Reasoning (Dialectics)

- Dianoia

- Dichotomous Thinking (Black-and-White Thinking; Dualistic Thinking; Polarized Thinking)

- Double Bind

- Doublethink

- Effort Paradox

- Elegant Solution

- Failure Paradox

- Fake Debate

- Fake Experts

- Fallacious Reasoning (Fallacy; Fallacious Argument; Logical Fallacy; Rhetological Fallacy; Specious Reasoning)

- False Analogy

- False Dichotomy (False Dilemma)

- Fuzzy Trace Theory

- Genealogy

- Growth Paradox

- Hasty Generalization

- Idée Fixe (Fixed Belief; Fixed Idea)

- Ignorance

- Ignorance Studies

- Immune to Evidence

- Impossible Expectations

- Inductive Reasoning

- Inoculation Theory

- Instrumental Rationality

- Intentionalism

- Irrationality

- Law of Parsimony (Economy Principle; Epistemic Simplicity; Principle of Economy; Principle of Parsimony)

- Learning Paradox

- Loaded Language (Emotive Language; High-Inference Language; language-Persuasive Techniques; Loaded terms)

- Logic

- Magnified Minority

- Mind Traps (Cognitive Distortions; Negative Automatic Thoughts; Thinking Errors; Thinking Traps; Thought Traps; Unhelpful Thoughts)

- Moral Reasoning

- Motivated Reasoning Theory (Motivational Reasoning Bias)

- Moving Goalposts (in Denialism)

- Narrative Mode (Narrative Mode of Thinking)

- Naturalistic Fallacy

- Nefarious Intent

- Noesis

- Obscurantism

- Occam’s razor

- Overriding Suspicion

- Paradigmatic Mode (Paradigmatic Mode of Thinking)

- Paradoxical Thinking (Both/And Thinking)

- Paralogism

- Persecuted Victim

- Polylogism

- Practical Reason (Practical Rationality)

- Pragmatic Reasoning Schema Theory

- Probabilistic Thinking

- Pseudoskepticism

- Quote Mining

- Reason (Ratiocination; Rational Thinking)

- Red Herring

- Red Pill and Blue Pill

- Re-Interpreting Randomness (Attributing Causality to Coincidence)

- Scientific Reasoning

- Science Denialism (Denialism)

- Scientism

- Skepticism

- Slippery Slope

- Slothful Induction

- Straw Man

- Synthetic Thinking (Synthetic Approach; Systemic Approach; Systemic Thinking)

- Thought-Terminating Cliché (Bumper-Sticker Logic; Cliché Thinking; Semantic Stop Sign; Thought-Stopper)

- Two-Plus-Two Phenomenon

- Value Rationality

- Willful Ignorance

- Something Must Be Wrong

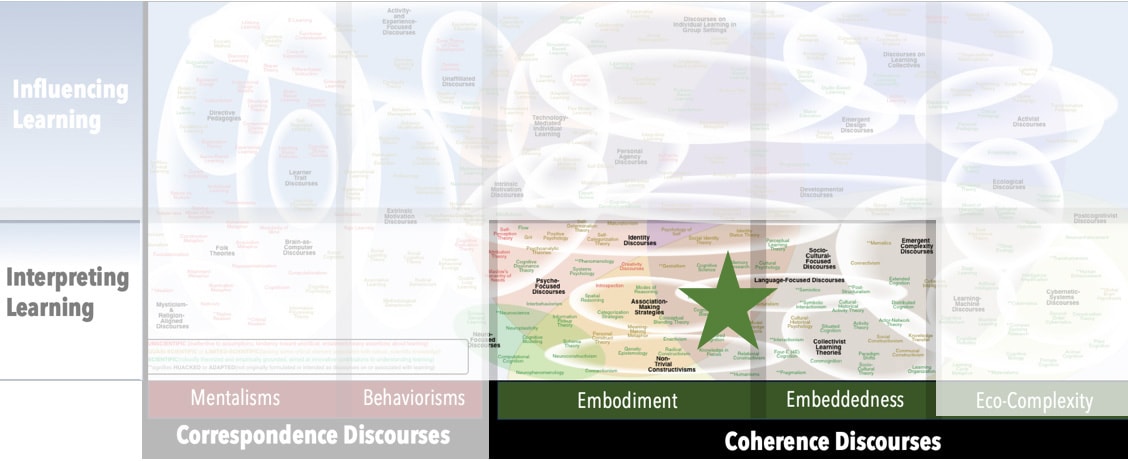

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Modes of Reasoning” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List