Focus

Using evidence and experience to affect conceptualizationsPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … currently accepted (but always-evolving) conceptualizations

- Knowing is … coherently interpreting

- Learner is … a sense-maker (individual)

- Learning is … accommodating (adapting, revising, replacing)

- Teaching is … interrupting; challenging

Originated

1980sSynopsis

The multiple interpretations of Conceptual Change in the education literature converge around the point that it has to do with restructuring, problematizing, or replacing an existing conception or categorization to give way to a new or more fitting one. Notions that are foundational to Conceptual Change include:- Concept Formation (Concept Learning) – a multifaceted process of abstracting and extrapolating a general idea from specific experiences, which involves one or more Modes of Reasoning

- Ontological Categories (Edmund Husserl, 1910s) – the most general of categories, which in turn correlate of types of meanings. Examples include object, attribute, event, relation, concept, and process. Ontological Categories are used to organize, develop, and contrast understandings of reality.

- Percept – a conscious noticing

- Concept – an integrated network of associations, abstracted from a class of Percepts, that is useful for making sense of and acting upon that class

- Schema – the subjective network of associations that constitutes a Concept (see above) for someone. Within the discourse of Conceptual Change, Concept is almost always treated synonymously with Schema.

- Features (Attributes) – characteristics of a Concept (e.g., a poodle has curly hair and can typically bark). Categories of Features include:

- Defining Features – those Features that must be present in all cases of a given Concept (e.g., a curly hair is a Defining Feature of a poodle, but being able to bark is not)

- Correlational Features – those Features that might be present in most or all cases of a given Concept but that aren’t necessary (e.g., almost all poodles can bark, but those that can’t are still poodles)

- Irrelevant Features – those Features that might be present in in cases of a Concept but that don’t matter to the concept (e.g., all the poodles living with Brent are black)

In some conceptual domains, such as mathematics, Features are either Arbitrary or Necessary:

- Arbitrary (Dave Hewitt, 1990s) – those Features of a Concept that are not assigned by choice, habit, or history, but that do not alter the Concept if changed (e.g., the words “one” and “plus” and the symbols “1” and “+” are Arbitrary – as evidenced by the fact that they’re named differently in French and Swahili, but the underlying Concepts are stable)

- Necessary (Dave Hewitt, 1990s) – those Features of a Concept that can be derived because they are logically obligatory (e.g., once “1”, “2”, and “+” are defined, it is Necessary that 1 + 1 = 2)

As for the implications for teaching, educators are advised to consider the relative merits of two major modes of sequencing, the most appropriate of which will be dependent on both the concept at hand and the learners:

- Sequential Presentation – experiences are structured so that learners encounter a series of Features, with the intent to render a concept more and more sophisticated over time

- Simultaneous Presentation – experiences are structured so that learners encounter more or all Features at the same time

Commentary

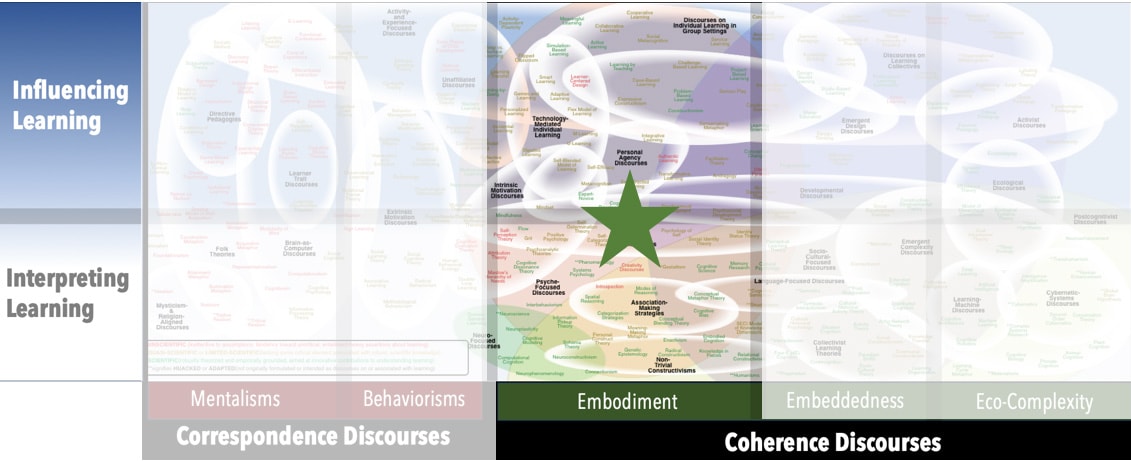

Conceptual Change finds its roots in Jean Piaget’s Genetic Epistemology and Thomas Kuhn’s Paradigm Shifts, and so it generally sits comfortably among other Coherence Discourses. However, there is a strong trend among some proponents to ignore the collective knowledge component of the theory and thus interpret Conceptual Change in terms of strategies to compel learners to come to forego their “naïve beliefs” or “misconceptions” in favor of “correct” conceptualizations. That is, in the current educational world, principles rooted in Correspondence Discourses are routinely and inappropriately imposed on Conceptual Change.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Susan CareyStatus as a Theory of Learning

Conceptual Change has robust roots in Genetic Epistemology and theories of cultural evolution. In does not, however, elaborate on those roots.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Conceptual Change is principally concerned with interpreting learner conceptualizations and structuring experiences to occasion learners to adjust or reject those conceptualizations. That is, Conceptual Change is mainly a theory of influencing learning.Status as a Scientific Theory

Conceptual Change is explicit about principles of learning and proponents have been attentive to accumulating evidence to support the theory. It is thus appropriately described as scientific according to the criteria we’re using.Subdiscourses:

- Arbitrary

- Concept

- Concept Formation (Concept Learning)

- Correlational Features

- Defining Features

- Features (Attributes)

- Irrelevant Features

- Necessary

- Ontological Categories

- Percept

- Schema

- Sequential Presentation

- Simultaneous Presentation

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2023). “Conceptual Change” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List