Focus

Exploring and exploiting structures that support collective generation of new possibilitiesPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … situation-relevant actions and interpretations

- Knowing is … effective contributions to joint activities

- Learner is … a collective entity (defined by a purpose or a task)

- Learning is … elaborating current possibilities

- Teaching is … coaching, supporting

Originated

1990sSynopsis

Discourses on Learning Collectives are concerned with matters of designing tasks, designating roles, and structuring situations in ways that support the maintenance and elaboration of teams, organizations, and other social collectives. Associated discourses include:- Collective Responsibility – in the context of Discourses on Learning Collectives, the distribution of blame for a shortcoming or atrocity all members of collective (e.g., population, employee base, cultural group, school staff, classroom grouping, etc.)

- Communal Learning – a collective, interactive process where knowledge is co-created through shared experiences, dialogue, and cultural contexts. Communal Learning emphasizes interdependence, oral traditions, and Experiential Learning, often seen in Indigenous Knowledge systems, a Professional Learning Community, and collaborative education models. It fosters continuous, socially embedded learning.

- Computer-Supported Collaborative Work (Irene Greif, 1980s) – research into the uses of digital technologies to support collaborative efforts. The field draws heavily on Psychology and Sociology, and it is oriented toward the development of more effective tools to support collaborative efforts.

- Conflict Management (Robert R. Blake, Jane Srygley Mouton, 1960s) – any strategy intended to enhance group learning and cohesion by exploiting the positive aspects of conflict and minimizing the negative aspects

- Forming–Storming–Norming–Performing Model of Group Development (Bruce Tuckman, 1960s) – a four-phase model that is suggested to be both an strategy to nurture collegiality and an approach to collective problem-solving (involving identifying a challenge, grappling with it, implementing a solution, and producing results)

- Group Agency (Shared Agency) – a collective-based sort of intention and engagement that cannot be attributed or reduced to solitary agents (Compare: Personal Agency Discourses.)

- Group Decision Support Systems (GDSS) – communication, record-keeping, and other technologies designed to improve group processes – by, for example, signalling possible errors or unnecessary redundancies, facilitating interactions, and enabling quick voting.

- Institutional Theory (various, mid-1900s) – an umbrella category that reaches across theories that frame organizational dynamics and management practices in terms of social norms, rules, and other processes (vs., e.g., economic pressures). Associated constructs and discourses include:

- Institutional Logic (Roger Friedland, Robert Alford, 1990s) – an Institutional Theory that attends to the influences of social and cultural belief systems on the thoughts and behaviors of individuals within an organization (contrast: Institutional Work, below)

- Institutional Work (Thomas Lawrence, Roy Suddaby, 2000s) – an Institutional Theory that attends to the manners in which individual agents affect institutions and businesses (contrast: Institutional Logic, above)

- Neo-Institutional Theory (Institutionalism; Neo-Institutionalism; New Institutionalism) (John Meyer, 1970s) – an Institutional Theory that focuses specifically on the effects on organizations of rules, both explicit/formal and implicit/informal, that impact the actions and interactions of individual and groups. Three strands or types of Neo-Institutional Theory are commonly identified:

- Historical Institutionalism (Kathleen Thelen, Sven Steinmo, 1990s) – a Neo-Institutional Theory concerned with dynamics over extended temporal periods – and that, in consequence, offers vantages on complex entanglements of politics, culture, and economics while highlighting the potential importance of accidents and seemingly minor happenings. Subdiscourses include:

- Critical Institutionalism – a branch of Historical Institutionalism that is oriented toward uncovering and critiquing overt and convert power structures associated with the rise and evolution of institutions

- Rational Choice Institutionalism (Kenneth Shepsie, 1980s) – a Neo-Institutional Theory that interprets the rise of institutions in terms of the systematic and intentional actions of political agents. Rational Choice Institutionalism is grounded in:

- Rational Choice Theory (Adam Smith, late-1700s) – a perspective on social and economic behavior that assumes one’s choices are driven by self-interest

- Sociological Institutionalism (Cultural Institutionalism; Sociological Neoinstitutionalism) (John Meyer, 1970s) – a Neo-Institutional Theory oriented by the suggestion that the structures and dynamics of organizations are often matters of ritual and ceremony rather than purposeful function. The theory is focused on how meaning is created and sustained by and for individuals through such dynamics and structures. Subdiscourses include:

- Global Neo-Institutionalism (World Polity Theory; World Society Theory) – a framework within Sociological Institutionalism that is focused on transnational relations and and global social change

- Indigenous Institutional Theory (Stacey Coates, Michelle Trudgett, Susan Page, 2020s) – a blend of Institutional Theory and Indigenous Standpoint Theory (under Positioning Theory) that is intended to enable the study of Indigenous experiences in post-secondary education

- Historical Institutionalism (Kathleen Thelen, Sven Steinmo, 1990s) – a Neo-Institutional Theory concerned with dynamics over extended temporal periods – and that, in consequence, offers vantages on complex entanglements of politics, culture, and economics while highlighting the potential importance of accidents and seemingly minor happenings. Subdiscourses include:

- Post-Institutionalism (Loet Leydesdorff, 2000s) – an Institutional Theory that applies insights and constructs of Complex Systems Research and Enactivism to the emergence and self-maintenance of institutions and ecosystems of institutions

- Open System Theory – a theory that views the organization as shaping and shaped by its environment. With regard to the former, the organization is seen as transforming inputs (i.e., human and physical resources) into outputs (i.e., goods and services) that influence the environment

- Prisoner’s Dilemma (Merrill Flood, Melvin Dresher, 1950s) – On matters of “cooperation vs. competition” and “individual vs. collective,” the Prisoner’s Dilemma is a case in point illustrating that rational individuals always have some level of motivation to make decisions and choices that will impair or constrain the possibilities for the group.

- 7 Levels of System Intervention (Daniel Kim, 1990s) – a framework comparing different ways to intervene in a system to produce desired changes or improvements. Seven leverage points are ranked, ranging from superficial changes to deep structural shifts: Events; Patterns of Behavior: Systemic Structures; Mental Models; Shared Vision; Team Learning; Personal Mastery.

- Social Information Processing – all processes associated with the creation, movement, application, impact, and maintenance of information within and across social systems. Narrow interpretations and applications of the notion include:

- Social Information Processing (Kenneth Dodge, 1990s) – the encoding and processing of information associated with social interactions

- Social Information Processing Theory (Joseph Walther, 1990s) – a perspective on the development and maintenance of digitally-mediated human relationships. It focuses in particular on relational qualities and opportunities that ware difficult or unlikely in/as face-to-face relationships.

- Staffing Theory (formerly: Manning Theory) (Roger Barker, Paul Gump, 1960s) – a sociocultural- and ecological-informed discourse that focuses on organizational functioning associated with staffing, especially as related to over- and under-staffing

- Team-Building (2010s) – a component of many collectivist-oriented discourses on learning. Team-Building focuses on establishing and maintaining “teamwork,” which is distinguished from “groupwork” and “cooperation.” That is, “teamwork” is generally regarded as a mode of collaboration in which all participants are invested, decision-making is mainly democratic, each member is able to work from their strengths, and duties are distributed respectfully. Concisely, a “team” is more a collective learner than a collection of learners.

- Values Education – explicit schooling on principles of acting, moral standards, and ethical codes that define what is acceptable in an organization or community

- Morphic Field (Morphic Resonance; Morphogenetic Resonance) (Rupert Sheldrake, 1980s) – a widely criticized and as-yet unsubstantiated proposal that agents can tap into the accumulated memories of many agents. The perspectives is used to account for collective memory, the movement of information between agents, and the transfer of learnings for an agent to its descendants.

Commentary

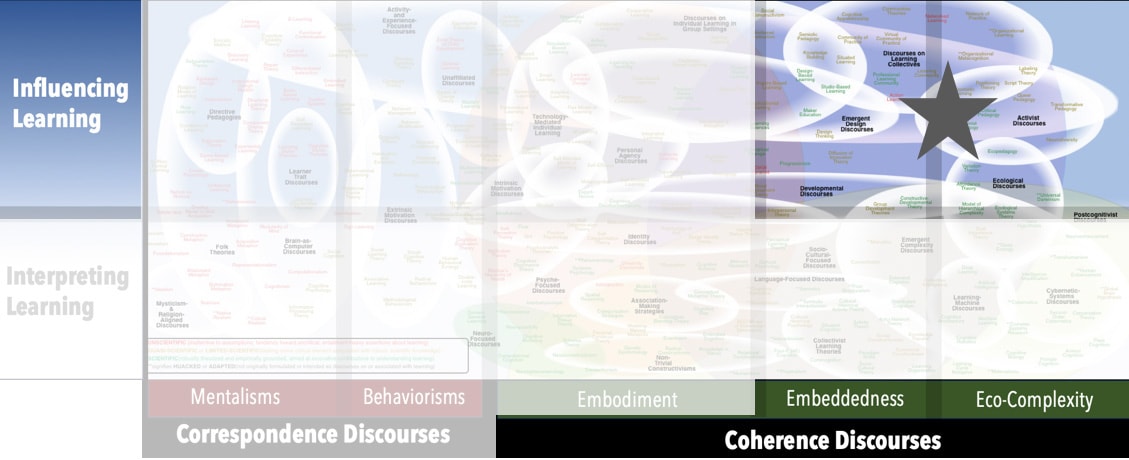

With the rise in prominence of Collectivist Learning Theories since the 1970s, advice to educators has split into two principal streams: Discourses on Individual Learning in Group Settings and Discourses on Learning Collectives. The former cluster is encountered much more frequently in education literatures, but the latter is more prominent in the world of business. That difference is perhaps unsurprising, given education’s legacy of focusing on individuals, which contrasts sharply business’s emphasis on continuous innovation.Subdiscourses:

- Collective Responsibility

- Communal Learning

- Computer-Supported Collaborative Work

- Conflict Management

- Critical Institutionalism

- Forming–Storming–Norming–Performing Model of Group Development

- Global Neo-Institutionalism (World Polity Theory; World Society Theory)

- Group Agency (Shared Agency)

- Group Decision Support Systems (GDSS)

- Historical Institutionalism

- Indigenous Institutional Theory

- Institutional Logic

- Institutional Theory

- Institutional Work

- Morphic Field (Morphic Resonance; Morphogenetic Resonance)

- Neo-Institutional Theory (Institutionalism; Neo-Institutionalism; New Institutionalism)

- Open System Theory

- Post-Institutionalism

- Prisoner’s Dilemma

- Rational Choice Institutionalism

- Rational Choice Theory

- 7 Levels of System Intervention

- Sociological Institutionalism (Cultural Institutionalism; Sociological Neoinstitutionalism)

- Staffing Theory (Manning Theory)

- Team-Building

- Tragedy of the Commons

- Values Education

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Discourses on Learning Collectives” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List