AKA

Instructional Design Theory

Instructional Systems Design Models

Instructional Theory

Focus

Teacher-directed approaches to influencing learningPrincipal Metaphors

Instructional Design Models are not associated with a specific perspective on learning. They are most often linked to the full spectrum Correspondence Discourses, across which notions associated with the Acquisition Metaphor and the Attainment Metaphor figure most prominently:- Knowledge is … material; domain

- Knowing is … recalling; applying

- Learner is … recipient; seeker (individual)

- Learning is … acquiring; attaining

- Teaching is … directing

Originated

Varied, commencing 1940sSynopsis

Instructional Design Models are usually articulated as frameworks and rubrics to support systematic design, development, and presentation of lessons or sequences of lessons. There are many subtle variations, but most Instructional Design Models involve identifying learning needs, specifying desired outcomes, crafting a plan to achieve those outcomes, and devising a strategy to assess whether the outcomes are achieved. Regarding the phenomenon of learning, most Instructional Design Models assume the following:- Analytical Learning (Explanation-Based Learning; Knowledge-Based Learning) – the combined assumptions that all necessary knowledge can be rendered explicit and that learning obeys predictable linear sequences – which, together, are typically encountered in curriculum structures that revolve around fragmenting knowledge into component parts and organizing it logically

- Linear Program – a sequence of topics that all students are expected to follow, typically at the same pace

- Branching Program – an instructional design that offers an array of trajectories through topics, typically based on student performance but often incorporating student interest

- Spiral Curriculum (Jerome Bruner, 1960s) – an instructional design that involves revisiting of topics and themes (both across courses or across grades), each time in more sophisticated ways, to deepen understanding and to knit ideas across subject areas

- Disciplines Thesis – the proposal that all knowledge can be unproblematically divided into discrete domains or disciplines, according to their distinct concepts, specific logics, and criteria for truths. Two prominent examples include:

- Forms of Knowledge (Paul H. Hirst, 1960s) – subscribing to the Disciplines Thesis, eight disciplines were proposed as a “bridge” between the human mind and the real world: Mathematics, Physical Science, History, Religion, Philosophy, Arts, Morals/Ethics, Social Science

- Realms of Meaning (Philip H. Phenix, 1960s) – subscribing to the Disciplines Thesis, six fundamental patterns of meaning were proposed to counter feelings of fragmentation, cynicism, meaninglessness, and inadequacy: Symbolics, Empirics, Esthetics, Synnoetics, Ethics, Synoptics

- Concept Analysis – examining the origins, applications, representations, and interpretations of a concept, as well as underlying definitions and relationships to other concepts, for the purposes of designing appropriate learning experiences (compare: Task Analysis)

- Task Analysis – examining a learning activity for the purpose of ensuring that participants have (or will be able to develop) the physical skills, analytic competencies, and conceptual understandings for a reasonable level of success (compare: Concept Analysis; Cognitive Task Analysis)

- Cognitive Task Analysis – a variety of Task Analysis that also includes examination of the Cognitive Processes associated with the task

- Backward Design (Ralph Tyler, 1942) – Three-stage model: 1. Identify desired results. 2. Identify acceptable evidence of learning. 3. Design teaching and learning experiences.

- Model of School Learning (Carroll Model; Carroll's Model of School Learning) (John Carroll, 1963) – an attempt to explain variations in school learning in terms of two clusters of variables. One cluster focused on achievement: Quality of Instruction, and Ability to Understand Instruction. The other focuses on time: Aptitude (the time needed for a student to learn the content), Opportunity to Learn (see below), and Perseverance (the time that a student is willing to devote to learning the content). In more detail ...

- Opportunity to Learn (John Carroll, 1963) – originally, the amount of time that a student is allowed for learning – which is seen to vary with learner aptitude and perseverance, as well as the quality of instruction. Opportunity to Learn has since been elaborated. In most current uses, it refers to the extent to which students and teachers have access to the resources and supports necessary for academic success.

- Conditions of Learning (Robert Gagné, 1968) – Model that assumed a linear, hierarchical model of learning. It specifies nine possible instructional events (gaining attention, informing about objective, stimulating recall, presenting stimulus, providing guidance, eliciting performance, providing feedback, assessing performance, enhancing retention).

- Personalized System of Instruction (PSI; Keller Plan) (Fred Keller; 1968) – Model of undergraduate-level teaching with five defining features: self pacing; Mastery Learning; teaching activities seen as motivational (versus as delivery of information); strong emphasis on written teacher–student communications; use of teaching assistants for testing, scoring, tutoring, and social connection.

- ADDIE Model (Florida State University, 1975) – Five-phase model: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation. Originally presented as a linear model. Current versions reinterpret the phases in terms of an iterative process:

- ADDIE+M (Pavlis Korres, 2010s) – the ADDIE Model with the addition of “Maintenance of te learning community network”

- PADDIE+M Model (United States Navy, 2010s) – the PADDIE Model with “Planning” pasted onto the start and “Maintenance” added the process has been implemented

- Pebble-in-the-Pond Instructional Design Model (David Merrill, 2000s) – an elaboration of the ADDIE Modelbased on an image of concentric circles (like the ripples formed when a pebble is dropped in a pond), by which each step of the model is characterized in terms of cyclical iterations rather than linear steps

- Criterion Referenced Instruction (Robert Mager, 1975) – A four-stage model: 1. Goal/task analysis. 2. Specification of learning outcomes. 3. Criterion-referenced evaluation. 4. Development of learning module. The model includes a comprehensive set of methods for each stage.

- Algo-Heuristic Theory (Lev Landa, 1976) – Model concerned with both conscious and non-conscious mental processes associated with expert performance. It revolves around a system of techniques to uncover the processes involved with expert performance. Associated discourses include:

- Landamatics (Lev Landa, 1990s) – a prescriptive teaching model based on Algo-Heuristic Theory involving mainly Authority Teaching Style and Guided Discovery Style (see Teaching Styles Discourses), with emphasis on assessment practices that match teaching styles

- Organizational Elements Model (Roger Kaufman, 1981) – A systemic model that focuses on gaps in performance. Three levels of systems (micro, macro, and meg) along with five system elements (inputs, processes, products, outputs, and outcomes) are identified.

- ASSURE (Robert Heinich, Michael Molenda, James Russel, Sharon Smaldion, 1982) – A six-stage process: Analyze learners, State standards and objectives, Select strategies, tools, and materials, Utilize technology, media, and materials, Require learner participation, Evaluate and revise.

- SOLO Taxonomy (John Biggs & Kevin Collins, 1982) – short for “Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome, the SOLO Taxonomy classifies learning objectives according to their complexity – and, thus, serves a basis for sequencing learning and for assessing the quality of student work: Prestructural (learner misses the point), Unstructural (learner notices one relevant aspect), Multistructural (learner notices multiple relevant aspects), Relational (learner coherently integrates aspects), Extended Abstract (learner generalizes)

- Component Display Theory (David Merrill, 1983) – Model that involve classifying and matching across several sets of distinctions: three learning actions (i.e., remembering, using, generalizing), four knowledge types (i.e., fact, concept, procedure, principle), four primary instructional strategies (e.g., exposition of general rules, exposition of specific examples, recall of generalizations, practice of specifics), and some secondary instructional strategies.

- Elaboration Theory (Charles Reigeluth, 1983) – Model that recommends prerequisites should be mastered before proceeding with a simple and personally meaningful version of the task or concept. Subsequent lessons should introduce new levels of complexity. Motivators, analogies, cognitive strategies, and openings for learner control should be designed into the teaching sequence.

- Knirk and Gustafson Model (Frederick G. Knirk, Kent L. Gustafson, 1986) – Three-stage process: 1. Identify problem and goals. 2. Design and develop objectives. 3. Specify strategies.

- Spiral Model (Barry Boehm, 1986) – The original spiral model of instructional design, comprising five iterative steps: define, design, demonstrate, develop, and deliver)

- ARCS (ARCS Model of Motivational Design) (John Keller, 1987) – A motivation-focused model, structured in two major parts: components of motivation (interest, relevance, expectancy, satisfaction) and instructional design to realize those components

- Hannifin-Peck Model (Michael J. Hannifin, Kyle Peck, 1987) – Three-phase model: 1. Needs assessment. 2. Design. 3. Develop and implement instruction. Evaluation and revision are components of all three phases.

- Outcome-Based Education (William Spady, 1988) – Originally, Outcome-Based Education was more-or-less typical among Instructional Design Models – and a clear example of Backward Design – distinguished slightly in its emphases on providing clear pictures of culminating outcomes of schooling and laying out high expectations for success. The model was picked up by several countries in the 1990s, and it was quickly attached to accountability measures (e.g., achievement tests) and coupled to accreditation. More recently, a softened version, shorter-term version has become popular, which revolves around teachers providing learners with explicit information on the following:

- Intended Learning Outcome (ILO) – a user-friendly statement, presented to learners prior to a learning activity or lesson sequence, on what they will be able to do when they complete that activity or sequence.

- Outcome-Based Assessment (Outcomes-Based Assessment) – criterion-referenced assessment based on measurable (and, often, observable) student products or performances. The outcomes and the criteria for assessment should be specified in user-friendly terms at the start of a learning event.

- Cognitive Apprenticeship (Allan Collins, John Seely Brown, Susan E. Newman, 1989) – Model focused on master–apprentice relationships. On the master’s side, the model is concerned with critical elements of the skill, supervision, and feedback. On the apprentice’s side, it is concerned with practice, mastery, and reflection.

- Minimalist Theory (Minimalism) (John M. Carroll, 1990) – Picking up on the core themes of Learning-by-Doing, Minimalist Theory recommends that learners be provided with minimal (and sometimes flawed and/or incomplete) information for the tasks to be performed. It is supported by a handful of studies that demonstrated that, in some situations, people provided with such information learn faster and perform better than those who have access to comprehensive materials and instruction.

- Rapid Prototyping (Steven D. Tripp, Barbara Bichelmeyer, 1990) – Model based on a continual design–evaluation iterative cycle. Elements include defining the concept, implementing a skeletal system, refining based on user evaluation, implementing refined version, refining based on user evaluation, etc.

- Constructivist Instructional Design (David Merrill, 1991) – a compilation of recommendations for teachers. The advice is claimed to be anchored to Non-Trivial Constructivisms, but it is more reflective of Progressivism. Foci include seeking learner input, posing relevant problems, pursuing big ideas, challenging learner assumptions, and assessing learning while teaching. Specific design elements include strategies for organizing, integrating, and highlighting critical information. In practice, however, Constructivist Instructional Design is often more heavily influenced by ideology than learning theory – as manifest, for example, in insistences that authority be distributed, classes be small, and teachers act as guides.

- Goal-Based Scenarios (Roger Schank, 1992) – Model that combines Case-Based Learning and Learning-by-Doing, framing the teaching engagement by specifying a goal that involves a sequence of steps.

- Whole–Part–Whole Learning (Richard Swanson & Bryan Law, 1993) – an instructional approach of topics that begins with preparing learners by situating the topic as a whole (e.g., linking to what is known; contextualizing), proceeds by developing parts (i.e., components of the whole), and culminates in consolidating a second whole

- Interpretation Construction Design Model (ICON Design Model) (John Black, Robbie McClintock, 1995) – a mash-up of several other Instructional Design Models, focused on meaningful tasks through which learners collaborate to develop defensible interpretations under the guidance of a teacher

- Rothwell & Kazanas Instructional Design Model (William J. Rothwell, H.C. Kazanas, 1998) – Ten-element cycle: needs assessment, learner characteristics, work characteristics, job/task analysis, performance objectives, performance measurements, sequence of expectations, instructional strategies, instructional materials, evaluation of instruction.

- Teaching for Understanding (David Perkins, Chris, Unger, 1999) – a framework for instructional design founded on the assertion that there’s a difference between learning and understanding. Emphases include application, problem solving, and public displays of knowledge.

- BOPPPS (Instructional Skill Workshop Network, 2000s) – a six-component lesson structure: Bridge in (orienting attentions); Outcomes (making aims explicit); Pre-assessment (gauging current knowledge); Participatory learning (offering active engagements); Post-assessment (evaluating new learning); Summary (recapping main details)

- Rapid Instructional Design (Dave Meier, 2000) – Model aimed at substantial engagement, practice, and feedback that is based on four phases: Preparation (arousing interest), Presentation (contextualizing new content), Practice (integrating content), Performance (applying new knowledge).

- Model-Centered Instruction / Design Layers (Andrew Gibbons, 2001) – Model assumes several, quasi-independent layers of simultaneous design – e.g., the model/content layer, the strategy layer, the control layer, the message layer, the representation layer, the media-logic layer, and the management layer.

- 4C-ID Model (Four Component Instructional Design Model) (Jeroen van Merriënboer, 2002) – Model concerned with complex skills and real problems. It is focused on integration and coordinated performance; it distinguishes between supportive information and just-in-time information; it advocates a blend of part-task and whole-task practice.

- Gerlach-Ely Model (Vernom S. Gerlach, Donald P. Ely, 2003) – Model that mixes linear activities (five steps: content/objectives, pre-requisites, planning, evaluation, post-analysis) and concurrent activities (five simultaneous tasks: strategy, groupings, timing, space, resources).

- Task-Based Learning (Task-Based Instruction; Task-Based Language Learning) (Rod Ellis, 2003) – a language-learning lesson structure, comprising three elements: (1) Pre-Task, to set expectations and provide instructions; (2) Task, aimed at fluent language-use in small groups; (3) Review, involving honest (and preferably peer-based) assessments of performance

- Response to Intervention (RtI) (Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 2004) – a system involving universal screening and ongoing assessment aimed at identifying and supporting learners at risk through early, tailored, and intense support. RtI identifies three tiers of instruction: Tier 1 – Universal, Core Classroom Instruction (~80% of students); Tier 2 – Targeted, Specialized-Group Instruction (~15% of students; sometimes split into two subgroups, depending on whether the intervention involves pull-out from the classroom); Tier 3 – Intensive, Individualized Intervention (~5% of students).

- Dick and Carey Model (Walter Dick, Lou Carey, 2005) – Nine-stage model: 1. Goals. 2. Instructional analysis. 3. Prerequisite knowledge. 4. Performance Objectives. 5. Criterion-references test items. 6 Instructional strategy. 7. Formative evaluation. 8. Summative evaluation. 9 Reflection.

- Integrative Learning Design Framework for Online Learning (Nada Debbaugh, Brenda Bannan-Ritland, 2005) – Three-phase model: exploration (gathering information on context), enactment, and evaluation.

- Empathic Instruction Design (Merlijn Kouprie, Froukje Sleeswijk Visser, 2009) – Model that asserts the ability to empathize with learners is essential.

- Affective Context Model (5di Model) (Nick Shackleton-Jones, 2009) – framed as an alternative to the ADDIE Model (see above), a six-stage model: Define, Discover, Design, Develop, Deploy, and Iterate. Most often presented as a design strategy aimed at marketing through triggering people’s memories and manipulating their emotions.

- Kemp Design Model (Gary R. Morrison, Steven M. Ross, Jerrold E. Kemp, 2010) – Nine-step model: problems/goals, learner needs, subject content, objective, sequence, strategies, lesson, evaluation, resources.

- Multiple Approaches to Understanding (Howard Gardner, 2010) – a compilation of advice for bringing Multiple Intelligences (see Social Model of (Dis)Ability) to bear in classroom teaching. Matters addressed include selecting topics for study, designing effective introductions, using multiple representations alongside powerful metaphors and analogies, varying modes of engagement – all in manners consistent with principles of Multiple Intelligences.

- Successive Approximation Model (Michael Allen, 2020s) – an iterative, three-step design model influenced by Design Thinking, in which each phase involves evaluation, design &/or development, and prototyping &/or implementation (Note: should not be confused with the Successive Approximation of Operant Conditioning)

Finally, in an era of measured accountability, there are different perspectives on how to evaluate Instructional Design Models. Most of those focus on learner achievement and related outcomes. More nuanced perspectives include:

- Constructive Alignment (John Biggs, 2010s) – the extent to which insights from Non-Trivial Constructivisms are enacted in and align with the learning outcomes of an educational program

- Design-Focused Evaluation (Calvin Smith, 2010s) – an approach to evaluating educational systems that focuses on the alignment of inputs (e.g., curricula, learning resources, teaching) with the outputs (e.g., what is actually learned)

Commentary

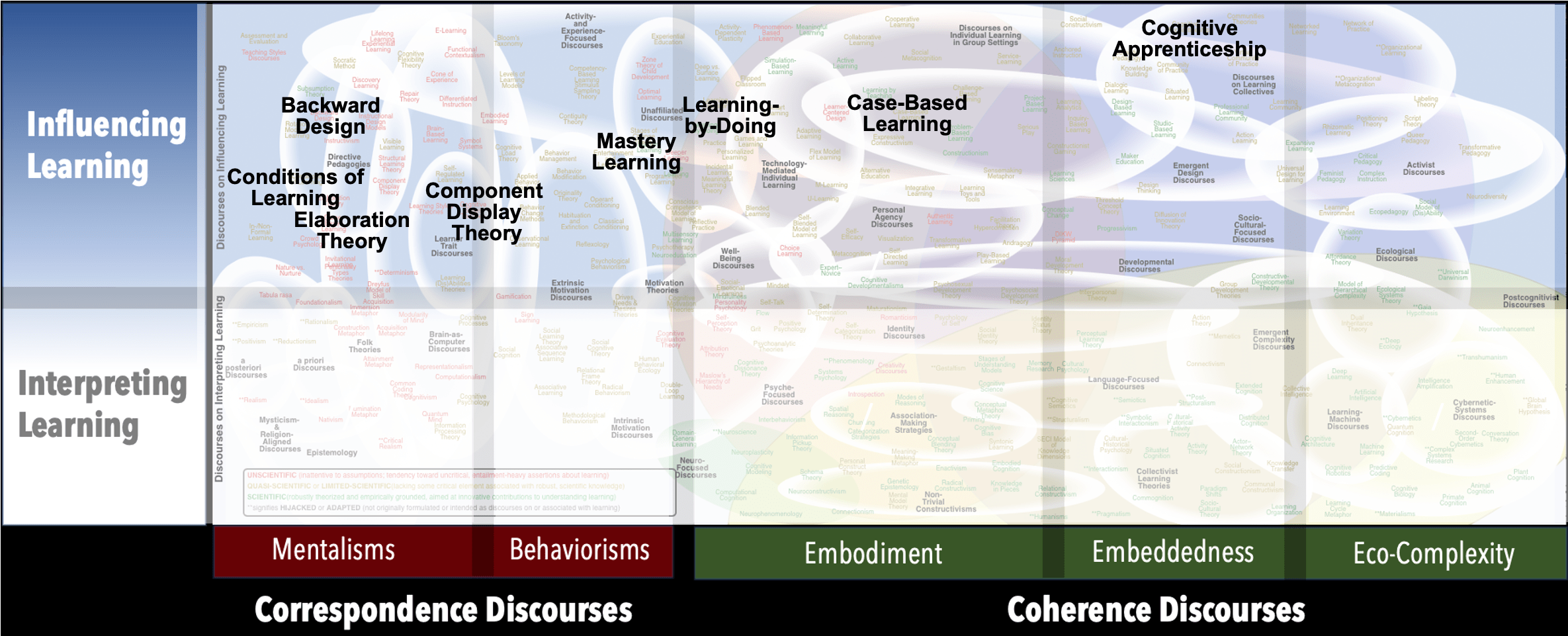

The immediate and obvious criticism of Instructional Design Models is presented in their shared title. Almost every one of them is an Instructivism, and so few are associated with current insights into learning. We have attempted to illustrate this point with the map (at the bottom of this entry), locating some of the more prominent discourses associated with Instructional Design Models. Another common criticism, shared with Instructivism, is that these design models tend to be very linear, inflexible, and time-consuming – that is, ill-fitted to the complex dynamics and circumstances of actual human learning. It is precisely for this reason that the competing realm of Learning Design was proposed in the 1980s – and, for that matter, why more recent Instructional Design Models have incorporated iterative and situated processes.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

DiffuseStatus as a Theory of Learning

Instructional Design Models are not theories of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Instructional Design Models are theories of teaching.Status as a Scientific Theory

Although frequently described as being based on principles of cognitive science, Instructional Design Models are perhaps better classified as “good advice” than “scientific theories.” They offer useful checklists and sequences to assist educators in thinking through and preparing for the many and diverse demands associated with teaching. However, they all fall well short of our criteria for scientific theories.Subdiscourses:

- ADDIE Model

- ADDIE+M

- Affective Context Model (5di Model)

- Algo-Heuristic Theory

- Analytical Learning (Explanation-Based Learning; Knowledge-Based Learning)

- ARCS (ARCS Model of Motivational Design)

- ASSURE

- Backward Design

- BOPPPS

- Branching Program

- Cognitive Apprenticeship

- Cognitive Task Analysis

- Component Display Theory

- Concept Analysis

- Conditions of Learning

- Constructive Alignment

- Constructivist Instructional Design

- Criterion Referenced Instruction

- Design-Focused Evaluation

- Dick and Carey Model

- Disciplines Thesis

- Elaboration Theory

- Empathic Instruction Design

- Forms of Knowledge

- 4C-ID Model (Four Component Instructional Design Model)

- Gerlach-Ely Model

- Goal-Based Scenarios

- Hannifin-Peck Model

- Integrative Learning Design Framework for Online Learning

- Intended Learning Outcome (ILO)

- Interpretation Construction Design Model (ICON Design Model)

- Kemp Design Model

- Knirk and Gustafson Model

- Landamatics

- Linear Program

- Minimalist Theory (Minimalism)

- Model-Centered Instruction / Design Layers

- Model of School Learning (Carroll Model; Carroll’s Model of School Learning)

- Multiple Approaches to Understanding

- Opportunity to Learn

- Organizational Elements Model

- Outcome-Based Assessment (Outcomes-Based Assessment)

- Outcome-Based Education

- PADDIE+M Model

- Pebble-in-the-Pond Instructional Design Model

- Personalized System of Instruction

- Rapid Instructional Design

- Rapid Prototyping

- Realms of Meaning

- Response to Intervention (RtI)

- Rothwell and Kazanas Instructional Design Model

- SOLO Taxonomy

- Spiral Curriculum

- Spiral Model

- Successive Approximation Model

- Task Analysis

- Task-Based Learning (Task-Based Instruction; Task-Based Language Learning)

- Teaching for Understanding

- Whole–Part–Whole Learning

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2024). “Instructional Design Models” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List