AKA

Psychological Therapy

Talking Therapy

Focus

Techniques designed to positively influence an individual’s mental healthPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … one’s habits, dispositions, and sensibilities, distilled from life’s experiences

- Knowing is … situational enacting (of identity)

- Learner is … client with pathology

- Learning is … confronting/managing/overcoming (pathology)

- Teaching is … therapy

Synopsis

Psychotherapy encompasses a range of techniques based on personal interaction that are intended to support mental well-being through influencing personal behaviors. It is associated with, but sometimes distinguished from, Counseling:- Counseling – relative to Psychotherapy, a (usually) shorter-term engagement that focuses on specific issues or life challenges, such as stress, grief, or relationship problems. Counseling tends to be more solution-oriented and practical.

- Uncovering – based on the metaphor of peeling away (i.e., layers of rationalization, repression, shame, etc.), the defining intention of Psychotherapy of moving beyond one’s symptoms to the matters that give/gave rise to those symptoms

Psychotherapies focused on the unconscious and/or embodied action

- Hypnotherapy (Franz Mesmer, late-1700s) – a therapeutic technique that uses guided relaxation, intense concentration, and focused attention to achieve a heightened state of awareness (hypnosis), helping individuals overcome psychological challenges, change habits, or manage pain by accessing the subconscious mind

- Somatic Psychology (Body Psychotherapy; Somatherapy) (Wilhelm Reich, 1880s) – focused on bodily experience. Somatic Psychology challenges the commonsensical mind–body dichotomy in the assertion that psychological issues always manifest bodily. Somatic Psychology is thus aimed at helping the client develop greater empathy for their experienced body, based on the conviction that an adequate awareness will enable healing. Specific techniques tend to be much more recent, and include:

- Mindful Somatics (2000s)– practices or strategies that blend Mindfulness and somatic (body-based) awareness, aimed at enhancing well-being, self-regulation, and connection between the mind and body, often to support healing, reduce stress, and/or improve emotional resilience

- Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (Pat Ogden, 2010s) – a type of Somatic Psychology developed to address trauma and attachment issues that aims to enable the body’s ability to heal itself by tuning into the body’s experience thought an integration of physicality, mindfulness, relationship, and agency

- Somatic Experiencing (Somatic Experiencing Therapy) (Peter Levine, 1990s) – oriented by the notion that the body can retain fragmentary memories in ways that are not directly accessible to the emotional and cognitive parts of the brain, a type of therapy intended to enable one to become aware of those memory fragments in ways that enable their integration with one’s conscious sense of self

- Somatic Practice (Somatics) (Thomas Hanna, 1970s) –a body-centered approach to awareness, healing, and learning that focuses on internal physical perception, movement, and sensation. Somatic Practice helps people reconnect with their bodies, often used in trauma recovery, therapy, and performance.

- Psychoanalysis (Depth Psychology) (Sigmund Freud, 1890s) – clusters of theories and techniques to address mental-health disorders and that focus on the unconscious mind. Many schools of thought have arisen (see the Psychoanalytic Theories). While commonly criticized, its influences are discernible in the assumptions, assertions, emphases, and/or techniques of most types of Psychotherapy.

- Existential–Humanistic Therapy (Humanistic–Existential Therapy) – a focus on the whole person, including subjective experiences, volition, and agency – in addition to behavior, cognition, and motivation

- Play Therapy – an approach to Psychotherapy in which children are enabled to “play out” (rather than narrate) emotions, internal conflicts, and relationship issues. Variations and associated techniques include:

- Directive Play Therapy – a type of Play Therapy in which the therapist actively orients attentions and structures situations

- Nondirective Play Therapy – a type of Play Therapy in which the therapist engages in flowing conversation with whatever engages the child’s immediate attentions, encouraging more productive ways of dealing with problems as opportunities arise

- Projective Play – a type of Play Therapy in which toys (usually dolls) are used to express feelings, act out relationship structures, and so on

- Psychoanalytic Play Technique (Melanie Klein, 1920s) – more aligned with Psychoanalytic Theories, the use of toys and play to encourage free, imaginative expression that are assumed to afford insight into unconscious desires and conflicts

- Puppetry Therapy – a type of Play Therapy involving the use of puppets

Psychotherapies focused on mind

- Psychodynamic Therapy (Psychodynamic Psychotherapy) – category of Psychotherapy in which a therapist/practitioner helps the patient/client to become more aware of conflicting aspects of their psyche and to resolve tensions by integrating those conflicting aspects

- Directed Thinking (Goal-Directed Thinking) – controlled, purposeful thinking involving deliberate use of language and concepts, all oriented to an explicit goal (e.g., solving a problem, or interpreting a complex situation), typically undertaken collaboratively or with guidance to reduce digressions and errors

- Affective Theory (various, early 1900s) – any approach to Psychotherapy that focuses on feelings and emotions at the principle site of therapeutic change

- Person-Centered Therapy (Carl Rogers, 1940s) – a humanistic approach emphasizing empathy, unconditional positive regard, and genuineness to help clients achieve self-actualization and personal growth in a nonjudgmental, supportive environment

- Constructivist Therapy (George Kelly, 1950s) – a therapeutic approach that focuses on how individuals construct meaning and make sense of their experiences, and so therapy aims at helping them reframe and reconstruct their perceptions and understanding of reality

- Cognitive Therapy (Aaron T. Beck, 1960s) – posits that shifting one’s habits of perception and interpretation is the key to lasting improvements to psychological problems. Treatment tends to be very collaborative and focused on affecting the individual’s thoughts, behaviors, and/or goals – often through the Socratic Method or similar technique.

- Expressive Therapies (Expressive Arts Therapy; Creative Arts Therapies) (varied authors, 1960s) – use art, dance/movement, drama, music, poetry, and/or psychodrama as sites of therapy. Oriented by the conviction that acts of creativity can afford a client more direct access to their body, their emotions, and their thoughts, Expressive Therapies emphasize the creative process (vs. the created product).

- Narrative Therapy (Michael White, David Epston, 1970s) – a therapeutic method that involves therapist and client in the co-authoring of new narratives to challenge dominant discourses and to foreground the personal values, skills, and knowledge that can be brought to bear on identified problems

- Voice Dialogue (Hall Stone, Sidra Stone, 1980s) – a therapeutic method that helps individuals recognize, engage, and balance different internal “voices” or sub-personalities to achieve greater self-awareness and emotional integration. Two voices are given special prominence:

- Inner Coach (Hall Stone, Sidra Stone, 1980s) – a supportive inner voice that fosters self-encouragement, self-compassions, confidence, and constructive personal growth by guiding without harsh judgment

- Inner Critic (Hall Stone, Sidra Stone, 1980s) – a harsh, judgmental inner voice that enforces perfectionism, self-doubt, and fear of failure. The Inner Critic develops from internalized societal and parental expectations.

- Cognitive Restructuring (S. Taylor, 1990s) – a process that targets “cognitive distortions” (i.e., maladaptive and irrational thoughts). Cognitive Restructuring typically involving identification, critique, and reframing of those distortions

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (John Teasdale, 1990s) – combines Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with principles and practices associated with Mindfulness. It is associated mainly with treatment of ailments that are chronic and disorders associated with trauma and stress

- Process Experiential Psychotherapy (Leslie Greenberg, 1990s) – an approach aimed at resolution of painful emotions in which the therapist focuses on immediate experiences to enable the client’s processing of troubling thoughts and emotions

- Cognitive Humanism (Richard Nelson-Jones; 2000s) – a mash-up of ideas and ideals from Psychotherapy, Buddhism, and Christianity, aimed at understanding what it means to be (and becoming) “fully human”

- Guided Imagery (Guided Affective Imagery, Katathym Imaginative Psychotherapy) (various authors, 2000s) – involves a teacher/practitioner helping a student/client to summon or simulate different sensory perceptions (usually focused on, but not limited to visual perceptions). It is applied in both formal learning situations and in therapy settings.

Psychotherapies focused on behavior

There is some debate, typically among those who subscribe to a mind–body dichotomy, as to whether an approach focused on behavior can be properly classified as psychotherapy. See, for example, approaches listed in the Behavior Modification entry. Other models caught up in this debate include:- Behavior Therapy (Behavioral Therapy; Behavioral Psychotherapy) (title attributed to Arnold Lazarus, but there were many innovators in the 1950s and 1960s) – broad category encompassing diverse approaches that incorporate techniques drawn from Behaviorisms into psychotherapeutic practices. Thus, aspects that can feature prominently include counterconditioning, rewards & punishments, habituation, systematic desensitization, functional analysis, and other techniques drawn from Behavior Modification.

- Primal Therapy (Arthur Janov, 1970s) – a Psychotherapy technique that revolves around loud and sustained screams, which are argued to treat psychological disorders by releasing and/or erasing pent up pain and negativity that has accumulated since the womb

Psychotherapies focused on mind and behavior

- Logotherapy (Meaning-Centered Therapy) (Viktor Frankl, 1950s) – an approach to Psychotherapy that focuses on helping the client overcome crises in meaning by examining three types of values: creative, experiential, and attitudinal

- Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (Rational Therapy; Rational Emotive Therapy) (Albert Ellis, 1950s) – assumes that humans construct emotional difficulties through irrational processes, and thus casts therapy as an educational process in which the client is taught to use more conscious and rational processes to identify, dispute, displace, and replace negative habits and processes.

- Transactional Analysis (Eric Berne, 1950s) – a psychological framework that examines human interactions based on three ego states—Parent, Adult, and Child. Transactional Analysis analyzes communication patterns, unconscious scripts, and emotional transactions to improve relationships, self-awareness, and personal growth, often used in therapy, coaching, and organizational settings.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Aaron T. Beck, 1970s) – combines behavioral and cognitive psychology to treat already-diagnosed mental disorders. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is practically oriented, so the therapist’s role is typically conceived in terms of working with the client to identify strategies that address specified goals. Associated constructs include:

- Behavioral Activation (BA) (1970s) – a structured, evidence-based psychological treatment that helps people improve their mood by increasing engagement in meaningful, pleasurable, or goal-directed activities – especially those they’ve been avoiding due to depression, anxiety, or trauma

- Cognitive Triangle (CBT Triangle; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Triangle) (Aaron Beck, 1980s) – the association of (or, more literally, a triangular shape used to depict the associations of) thoughts, behaviors, and feelings, highlighting their interconnections and mutual influence

- Structured Learning (Alfred Goldstein, Robert Sprafkin, Jane Gershaw, 1970s) – a multistage process focused on psychological skills training, involving deliberate modeling, role play, feedback, and transfer of learnings to other settings (Note: not to be confused with Structured Learning of Teaching Styles Discourses)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Marsha M. Lineham, 1980s) – combines emphases from several traditions, including emotional self-regulation from modern psychology and mindfulness practices from contemplative meditation traditions. It emphasizes acceptance of emotional dysfunction while exploring less-maladaptive alternatives, with an overarching goal of a “life worth living.”

- Narrative Psychology (Theodore Sarbin, 1980s) – a branch of Psychology that looks to one’s stories and storytelling as a principal means of defining oneself – and, so, a lens to examine and interpret one’s behavior

- Coherence Therapy (Bruce Ecker, Laurel Hulley, 2000s) – rejecting the commonplace assumption that psychological issues are rooted in irrational or pathological processes, Coherence Therapy regards out-of-control symptoms as sensible and coherent expressions of one’s mind–body system. Responses are thus not sought in verbal-cognitive exchanges but in analyses of nonverbal, emotional, perceptual, and bodily knowings, through which one’s resistance to change is engaged as an ally in therapy rather than an enemy.

- Pattern System (Periodic Table for Psychology) (Jay Earley, 2010s) – a psychological framework that maps behavioral patterns into 10 elemental dimensions of personality (i.e., intimacy, conflict, self-esteem, accomplishment, interpersonal boundaries, power, pleasure, spirituality, cognitive style, emotional regulation) – each of which encompasses both healthy capacities and potential dysfunctional patterns. The framework is intended to help individuals and therapists understand and transform maladaptive tendencies.

Psychotherapies with holist sensibilities

- Integrative Psychotherapy – umbrella term applied to approaches that aim to integrate elements from different schools. Loci of integration vary, and may include diverse techniques, theories, pathologies, and/or aspects of personality/being.

- Psychosynthesis (Roberto Assagioli, 1910s) – a Psychotherapeutic approach that focuses on integrating various aspects of the self (subpersonalities) and connecting with a transcendent aspect of one’s identity (“Higher Self”) for guidance, meaning, and a sense of purpose

- Gestalt Therapy (Frtiz Perls, Laura Perls, 1940s) – draws on insights from domains as diverse as Eastern philosophy, Phenomenology, Psychoanalytic Theories, Gestaltism, and Complex Systems Research. Gestalt Therapy focuses more on what is happening in the moment (e.g., what’s being done, thought, and felt) than on what might/could/should be. It is oriented by the conviction that greater awareness of what one is doing, along with the social and environmental contexts of one’s life, will enable/embolden one to effect significant and meaningful changes.

- Transpersonal Therapy (Abraham Maslow, Stanislav Grof, Anthony Sutich, 1960s) – focuses on one’s spirit, rather than one’s body or mind. Transpersonal Therapy is concerned with spiritual enlightenment, oriented toward humanity’s higher potentials and seeking insight into and realization of spiritual, unitive, and other transcendent modes of consciousness.

- Feminist Therapies (Susan Thomas, 1970s) – focused on socio-political and other cultural aspects of pathologies and solutions, especially among female clients. Feminist Therapies are concerned with interrupting social forces associated with sex, gender, sexuality, race, class, ethnicity, religion, age, and other categories of distinction. Feminist Therapies see the empowerment of the client as an integral element in any therapy.

- Multimodal Therapy (Arnold Lazarus, 1970s) – based on the assertion that, since humans are biological and social beings, psychological treatments should address multiple modalities. Seven, in particular, are identified: behavior, affect, sensation, imagery, cognition, interpersonal relationships, and drugs/biology (known by the acronym BASIC I.D.).

- EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy) (Francine Shapiro, 1980s) – a proven-to-be-effective treatment for a range of disorders (including PTSD, OCD, anxiety, and depression) that involves focusing on a trauma memory while experiencing bilateral stimulation of some part of the body, typically the eyes (suggested to activate both brain hemispheres)

- Nature-Guided Therapy (Ecotherapy) (George Burns, 1990s) – an approach to Psychotherapy rooted in the fact that human–nature interactions can enhance well-being, and so developed around mindful awareness of one’s sensory connections with nature

- Positive Psychology (Martin Seligman, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Christopher Peterson, Barbara Fredickson, 1990s) – the scientific study of “the good life.” It is sometimes described as a reaction to Psychoanalytic Theories and Behaviorisms, which are seen as negative, focused on maladaptive behavior, and driven by the past. In contrast, Positive Psychology looks to the future as it focuses on such qualities as positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and purpose.

- Beck’s Generic Cognitive Model (Aaron Beck, 2010s) – an elaboration of Beck’s earlier models of Cognitive Therapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (both described above) to incorporate advances in genetics, epigenetics, Cognitive Psychology, and other fields. It posits that every psychological problem can be decomposed into a specific “formulation,” which can then be used to tailor a strategy to address the pathology.

- Tripartite Model of Psychotherapy (Tripartite Learning) (Douglas Scaturo, 2010s) – a model of learning/therapy that brings together the emotional (in the therapeutic relationship), the cognitive (in the therapist’s deliberate interventions), and the behavioral (of patients in their broader worlds).

Psychotherapies invoking systems and network thinking

- Internal Family Systems (Richard Schwartz, 1980s) – an approach to Psychotherapy built on the assumption that one’s mind is a system of many discrete and distinct subpersonalities. The approach is oriented by Family Systems Theory (under Ecological Systems Theory) and draws on Systems Psychology to examine and influence the organization of these subpersonalities.

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy (Gerald Klerman, Myrna Weissman, 1970s) – an intensive form of Psychotherapy that focused on one’s interpersonal relationships as both sources of personal difficulties and sites of assistance

- Network Therapy – an approach to individual or family Psychotherapy that might involve members of the immediate and extended family, friends, neighbors, and others as supports

- Social-Network Therapy – a type of individual Psychotherapy that includes group sessions involving others who are in significant relationships with the client

- Systemic Therapy (Arist von Schlippe, Jochen Schweitzer, 1990s) – an approach to Psychotherapy the focuses on reformatting patterns of interaction in groups (e.g., families, workplace communities), rather than seeking causes or assigning diagnoses for psychological issues

Psychotherapies that may involve medications

- Psychiatry is a branch of medical science that attends to studying, preventing, diagnosing, and treating disorders that may manifest as maladaptations of emotion, behavior, thought, and/or perception. Client disorders are typically aligned with concepts and conditions listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, currently in its 5th edition). Treatments typically combine psychiatric medication with one or more types of Psychotherapy. Notable associated discourses include:

- Anti-Psychiatry – a movement that’s almost as old as Psychiatry, characterized by concerns about the reliability of psychiatric diagnoses, efficacy of treatments, potential harms of medications, inherent (gender, cultural, ethnic, and other) biases, and other matters

- Psychedelic Therapy – makes use of psychedelic (literally, “mind-manifesting”) substances to assist in recovery of repressed traumatic events and to manage extreme emotions, as well as to enhance the relationship between the therapist and client.

Psychotherapies defined by pragmatic results

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Comprehensive Distancing) (Steven C. Hayes, 1980s) – aiming at being present with what life brings, rather than eliminating difficult emotions. ACT techniques involve attending openly to the causes and consequences unpleasant feelings – not to overcome them, but to respond more productively in situations that provoke them.

- Brief Therapy (Brief Psychotherapy; Planned Short-Term Therapy) (Milton H. Erickson, 1970s) – focused on providing a direct intervention for a single, specified clinical or subjective condition. Brief Therapy is more solution-based than it is problem-focused, and so it devotes less energy to excavating a problem’s origins and more energy to addressing factors that sustain it. Pragmatically minded, Brief Therapy acknowledges there are likely many possible paths to a beneficial outcome. Decisions are thus based on observations of what seems to be working rather than imaginings of what should be working.

- Eclectic Psychotherapy is a descriptive term, used in reference to interventions in which the clinician drawn on multiple perspectives and sets of techniques in an ad hoc manner. Eclectic Psychotherapy is pragmatically oriented – concerned mainly with effectiveness in resolving problems rather than theoretical coherence.

- Human Givens Model (Joe Griffin, Ivan Tyrrell, 1990s) – proposes that humans have prespecified sets of physical needs (e.g., air, water, nutrition, sleep) and emotional needs (e.g., security, autonomy, status, privacy, attention, connection, intimacy, achievement, meaning). The model is concerned with supporting clients in developing strategies and using strengths to meet emotional needs.

- Reality Therapy (William Glasser, 1960s) – oriented by the assumption that psychological issues are rooted in failures to meet basic needs. To gain insight into how to meet one’s needs, Reality Therapy focuses on realism, responsibility, and right-and-wrong (rather than pathologies), it emphasizes the here-and-now (rather than the past), and it deals with one’s conscious realities (rather than unconscious processes).

- Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (Steve de Shazer, Insoo Kim Berg, 1980s) – a short-term, goal-oriented therapeutic approach that emphasizes finding solutions rather than focusing on problems, encouraging clients to identify strengths and resources to create positive change quickly

Group-focused approaches to Psychotherapy

- Family Therapy (Couple and Family Therapy; Family Counseling; Family Systems Therapy; Marriage and Family Therapy) (various, late 1800s) – a branch of Psychotherapy concerned with the nurturing and development of relational dynamics among family members. Specific types include:

- Couples Therapy (Couples Counseling; Marriage Counseling; Marriage Therapy; Relationship Education; Relationship Therapy) (various, 1920s) – a mode of Family Therapy that focuses on the viability and maintenance of the principal, family-defining adult relationship

- Multiple Impact Therapy (Impact Therapy) (University of Texas, 1950s) – a focused, short-term Family Therapy technique designed for families in extreme crisis

- Strategic Therapy – a mode of Family Therapy that focuses on patterns of interaction among family members

- Structural Therapy – a mode of Family Therapy that focuses on the structure (and possible re-structuring) of the family system

- Transgenerational Therapy – a mode of Family Therapy that focuses on problematical beliefs and patterns of behavior that families might maintain over generations

- Group Therapy (Group Psychotherapy) (1920s) – a group-based form of Psychotherapy that involves the deliberate use of relationships and group processes to influence personal functioning and well-being

- Strategic Family Therapy (Jay Haley, 1950s) – a therapeutic approach that focuses on changing specific behaviors within the family by using direct interventions, directives, and problem-solving strategies to alter dysfunctional patterns and achieve desired outcomes

- Structural Family Therapy (Salvador Minuchin, 1960s) – a therapeutic approach developed that focuses on restructuring family interactions by identifying and modifying dysfunctional family structures, hierarchies, and boundaries to promote healthier relationships

- Systemic Coaching – a Psychotherapy-based approach to understanding and improving team functioning that simultaneously focuses on individual well-being, interpersonal relationships, and collective dynamics.Systemic Coaching is informed by Complex Systems Research.

Commentary

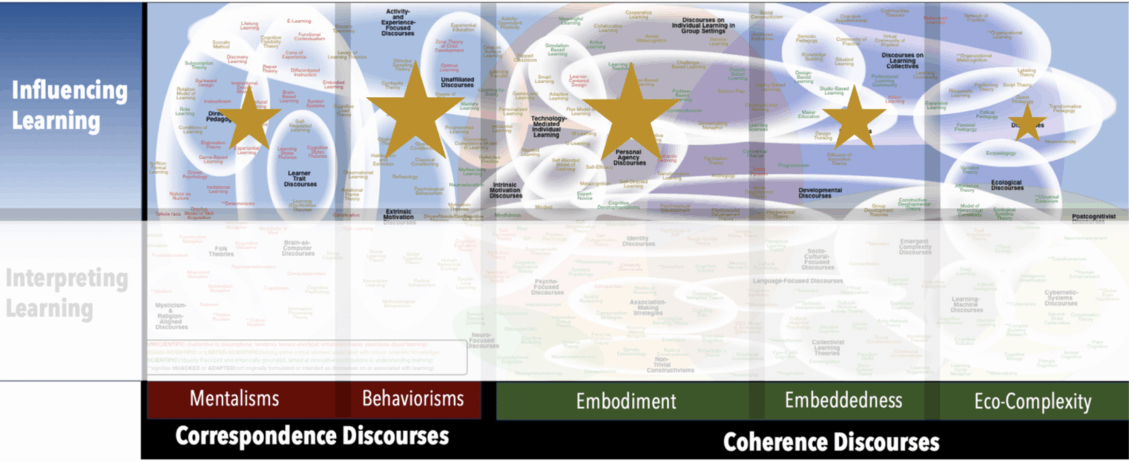

There is extensive criticism of the healing power of most types of Psychotherapy, typically on the grounds that specific approaches are too narrow in their considerations and strategies to effectively address the intricate complexities of even common pathologies. Over the past few decades, criticisms have concentrated more on the tendency to identify the individual client as the site of pathology, thus failing to adequately consider the contributions of, for example, environmental toxins, social structures, cultural norms, changing realites, and other more-than-self influences on mood, behavior, thought, and perception. More generally, Psychotherapy isn’t so much a “discourse” as it is an “endeavor.” It is a domain defined by a shared goal rather than common beliefs. To that point, all of the sensibilities and foci represented across the many discourses we’ve examined for this site are present among the collected schools of thought that cluster under the umbrella of Psychotherapy. (For simplicity and convenience – and based on both key historical elements and prominent contemporary emphases – we have assigned Psychotherapy to a discrete location on our map. A more appropriate map “location” would be a bubble that stretches horizontally across the map and that sits mainly in the upper region, “Discourses on Influencing Learning.”)Authors and Prominent Influences

Diffuse. A number of significant figures are identified in the brief descriptions of the specific approaches that are included in the Synopsis section, above.Status as a Theory of Learning

For the most part, specific types of Psychotherapy are grounded in but do not elaborate well-researched principles of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Psychotherapy is centrally concerned with addressing maladaptations related to temperament, behavior, thought, and/or perception. That is, Psychotherapy is principally focused on influencing learning – which, in our analysis, renders it a discourse on teaching.Status as a Scientific Theory

There is extensive criticism of the effectiveness (i.e., the healing power) of most types of Psychotherapy, typically on the grounds that specific approaches are too narrow in their considerations or strategies to effectively address the intricate complexities of even common pathologies. Over the past few decades, criticisms have concentrated more on the tendency to identify the individual client as the site of pathology, thus failing to adequately consider the contributions of social structures, cultural norms, evolving conditions, and other more-than-self influences on mood, behavior, thought, and perception. While virtually every school of thought claims both a sound theoretical grounding and significant empirical evidence, none appears to meet our criteria for a fully scientific discourse – owing in large part to contradictory theories and conflicting evidence associated with other schools of thought.Subdiscourses:

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Comprehensive Distancing)

- Affective Theory

- Anti-Psychiatry

- Beck’s Generic Cognitive Model

- Behavior Therapy (Behavioral Therapy; Behavioral Psychotherapy)

- Behavioral Activation (BA)

- Brief Therapy (Brief Psychotherapy and Planned Short-Term Therapy)

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Cognitive Humanism

- Cognitive Restructuring

- Cognitive Therapy

- Cognitive Triangle (CBT Triangle; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Triangle)

- Coherence Therapy

- Constructivist Therapy

- Counseling

- Couples Therapy (Couples Counseling; Marriage Counseling; Marriage Therapy: Relationship Education; Relationship Therapy)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy

- Directed Thinking (Goal-Directed Thinking)

- Directive Play Therapy

- Eclectic Psychotherapy

- EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy)

- Existential–Humanistic Therapy (Humanistic–Existential Therapy)

- Expressive Therapies (Expressive Arts Therapy; Creative Arts Therapies)

- Family Therapy (Couple and Family Therapy; Family Counseling; Family Systems Therapy; Marriage and Family Therapy)

- Feminist Therapies

- Gestalt Therapy

- Group Therapy (Group Psychotherapy)

- Guided Imagery (Guided Affective Imagery; Katathym Imaginative Psychotherapy)

- Human Givens Model

- Hypnotherapy

- Inner Coach

- Inner Critic

- Integrative Psychotherapy

- Internal Family Systems

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy

- Logotherapy (Meaning-Centered Therapy)

- Mindful Somatics

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

- Multimodal Therapy

- Multiple Impact Therapy (Impact Therapy)

- Narrative Psychology

- Narrative Therapy

- Nature-Guided Therapy (Ecotherapy)

- Network Therapy

- Nondirective Play Therapy

- Pattern System (Periodic Table for Psychology)

- Person-Centered Therapy

- Play Therapy

- Positive Psychology

- Primal Therapy

- Process Experiential Psychotherapy

- Projective Play

- Psychedelic Therapy

- Psychiatry

- Psychoanalysis (Depth Psychology)

- Psychoanalytic Play Technique

- Psychodynamic Therapy (Psychodynamic Psychotherapy)

- Psychosynthesis

- Puppetry Therapy

- Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (Rational Therapy; Rational Emotive Therapy)

- Reality Therapy

- Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

- Social-Network Therapy

- Solution-Focused Brief Therapy

- Somatic Experiencing (Somatic Experiencing Therapy)

- Somatic Practice (Somatics)

- Somatic Psychology (Body Psychotherapy; Somatherapy)

- Strategic Family Therapy

- Strategic Therapy

- Structural Family Therapy

- Structural Therapy

- Structured Learning

- Systemic Coaching

- Systemic Therapy

- Transactional Analysis

- Transgenerational Therapy

- Transpersonal Therapy

- Tripartite Model of Psychotherapy (Tripartite Learning)

- Uncovering

- Voice Dialogue

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Psychotherapy” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List