Focus

Attending to the collective aspects of human knowledge, activity, and identityPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … actions and interpretations that have been collectively developed and sanctioned

- Knowing is … situationally appropriate actions and interpretations

- Learner is … a participant in a collective

- Learning is … becoming a more expert participant

- Teaching is … modeling (i.e., acting as a more-expert agent while involving learners in culturally relevant experiences)

Originated

1960sSynopsis

Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses tend to operate from the assumption that collective knowing unfolds from and is enfolded in individual knowers. Consequently, most of these discourses attend the situated learner and/or the collective learning system – rather than the individual learner. Matters that figure prominently include context, participation, collaboration, ethics, democratic obligation, and tacit norms – often coupled to desires and efforts to prompt critical awareness. In the context of education, prominent notions associated with Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses include:- Appropriation of Knowledge (1990s) – Drawing on both Embodiment Discourses and Embeddedness Discourses, Appropriation of Knowledge is seen to occur when the individual has selected aspects of cultural knowledge and adapted them in ways that are personally meaningful and useful.

- Basic Personality – a sociocultural-focused (vs. individual-focused) construct that refers to the similar and distinct patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior among individuals brought up in the same culture – that is, subjected to the same child-rearing practices, immersed to the same cultural narratives, involved in the same patterns of social engagement, involved in the same institutions, etc.

- Behavior Setting Theory (Roger Barker, 1940s) – a perspective that is concerned with the study of human behaviors in their natural settings, and one that is intended to explain small-scale social systems. A “behavior setting” is a cultural form – particularly any social environment – that is useful for making sense across the dynamic individual activity and the stable social structures.

- Collective Conscience (Common Conscience) – the shared frame (comprising norms, values, beliefs, etc.) that enables a society or other significant collective to be cohesive [Note: Collective Conscience should not be confused with Collective Consciousness; see Crowd Psychology.)

- Continental Philosophy – an umbrella term used to refer to philosophical discourses that rose to prominence in Europe during the 20th century, including Phenomenology, Structuralism, and Post-Structuralism

- Cultural Studies – an umbrella term used to refer to various efforts to discuss contemporary texts and cultural practices. The ranges of interests and influences within Cultural Studies is very similar to those included in the Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses cluster on this site.

- Culture – in the context of Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses, the stable-but-evolving complex of values, beliefs, and behaviors of a defined group of people. Across Embeddedness Discourses the notion of Culture typically operates analogously to the notion of Identity (see Identity Discourses), but at a collective level.

- Discourse Analysis – the study of the sociocultural structures/frames that afford context and meaning to discussions, narratives, and arguments. Such structures/frames are often both implicit and ubiquitous. Consequently, they can be very difficult to excavate and interrogate – as might be illustrated by, for example, Ubiquitous Metaphors of Learning.

- Discourse Theories (Discourse Studies) (diffuse authorship, but Michel Foucault figures prominently; 1970s) – a cluster of theories and domains that share interests in better understanding communication, meaning, and the constitutive role of language in social, political, and cultural contexts. Most Discourse Theories address matters of power (i.e., discourses are shaped by power structures and, reciprocally, can serve either to maintain or interrupt those structures), knowledge (discourses arise in and legitimize understandings of truth and reality), and subjectivity (discourses are necessary for the creation, maintenance, and negotiation of identities and positionings). Most Discourse Theories align with the sensibilities of Post-Structuralism.

- Big “D” Discourse (James Paul Gee, 1990s) – a notion that reaches across ways of knowing, doing, and being – which are seen to arise in and reflect integrations of language, (inter)activity, beliefs, tools, and artifacts

- Little “d” discourse (Small “d” discourse) (James Paul Gee, 1990s) – the analysis of specific uses of language

- Discourse Analysis – the study of the sociocultural structures/frames that afford context and meaning to discussions, narratives, and arguments. Such structures/frames are often both implicit and ubiquitous. Consequently, they can be very difficult to excavate and interrogate – as might be illustrated by, for example, Ubiquitous Metaphors of Learning.

- Discourse Community (Martin Nystrand, 1980s) – a hazily defined notion that can be applied to any group of people who share some sort of orienting convictions (e.g., public goals, ideology, shared history, or religious belief) and who are able to communicate about those convictions. Associated constructs include:

- Boundary Crossing – most generally, the movement among or embrace of multiple Discourse Communities – such as, e.g., shifting from academic to non-academic contexts, moving across scholarly disciplines, traversing cultures, or working across more than one Community of Practice

- Boundary Object (Susan Star, James Griesemer, 1980s) – a phenomenon, either concrete (e.g., a technology, a map, a specimen) or abstract (e.g., an idea or belief) that can serve as a bridge between two sensibilities, communities, and/or cultures

- Boundary-Work (Thomas Gieryn, 1980s) – the matter of Boundary Crossing in specific relation to questions of what can be (and can’t be) considered scientifi

- Universe of Discourse – what can be said, heard, and understood in a Discourse Community, and how it can be expressed. The notion is often attached to matters of Power (see Activist Discourses), with the suggestion that elites often control the Universe of Discourse

- Discourse Routine – a highly structured interactive style in which there are clear expectations on turn taking, types of contribution, and so on. A familiar example of a Discourse Routine is the traditional school classroom

- Discursive Practice – a specific uses of language and/or a habit of acting associated with language that function to create discourse systems (e.g., color-coding babies in pink or blue represents a Discursive Practice of gender)

- Horizontal Discourse (Basil Bernstein, 1990s) – commonsensical, everyday knowledge that is typically specific to a Discourse Community – that is, Horizontal Discourse is localized, context dependent, and largely tacit. Contrast Vertical Discourse, below.

- Vertical Discourse (Basil Bernstein, 1990s) – highly organized, systematically validated, mainly explicit, and context-independent knowledge. Contrast Horizontal Discourse, above.

- Discursive Psychology (Jonathan Potter, Margaret Wetherell, 1980s) – the study of the roles of communication (verbal, gestural, written, etc.) in the construal of events and other aspects of subjective and social realities

- Enculturation – the transfer of a sense of cultural identity from one generation to the next – that is, coming to embody the tacit and explicit dimensions of one's culture through informal and formal encounters

-

Externalisms – accounts of thought, mind, and/or consciousness that assert that those phenomena do not fully happen or reside in the brain, but that also (and, in some discourses, principally) involve what occurs and exists beyond one’s skin (Note: should not be confused with Externalisms of Motivation Theories.)

- Impact Theory – any framework or model that analyzes how actions, interventions, or phenomena influence individuals, organizations, or systems. Impact Theories appear in psychology, education, social sciences, and business. Examples include:

- Social Impact Theory (Bibb Latané, 1980s) – a theory intended to gauge “social impact,” which is understood in terms of the influences that people have on one another. A multiplicative model is suggested that combines such factors as persuasiveness, expertise, attractiveness, proximity of personalities, and number of persons engaged.

- Dynamic Social Impact Theory (Bibb Latané, 1990s) – an elaboration of Social Impact Theory (see below) that attends to the creation and moulding of culture by local social influences. Four elements serve as the theory’s main foci: clustering (regional differences); correlation (emergent associations); consolidation (reductions in difference); continuing diversity.

- Object-Based Learning – Object-Based Learning is oriented by the conviction that a physical artifact can serve as a window into its context. That is, an object can afford insights into traditions, sensibilities, assumptions, and norms – and thus serve to focus multi-perspectival discussions, in-depth investigations, creative expression, and critical self-reflection.

- Participatory Epistemology (Participatory Theory) – Variously defined, most versions of Participatory Epistemology cluster around rejections of such dichotomies as subject/object, internal/external, and human/nonhuman as they assert that meaning arises through participation in the world.

- Participatory Learning – a loosely defined phrase that, depending on context, aligns with Discourses on Individual Learning in Group Settings or Discourses on Learning Collectives. Most often, Participatory Learning is engaged as a discourse to inform teaching.

- Postformalism (Joe Kincheloe, 1990s) – a theory designed to reject Correspondence Discourses while embracing (but blurring boundaries across) Embodiment Discourses and Embeddedness Discourses, while particular emphasis placed on Activist Discourses.

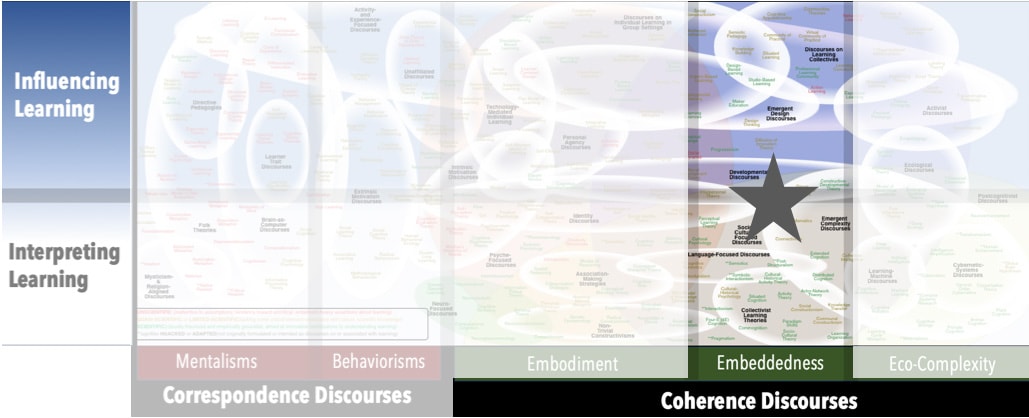

- Practice Theory (Praxeology; Social Practice Theory; Theory of Social Practices) (Pierre Bordieu, 1970s) – an umbrella category that includes those Socio-Cultural Focused Discourses that are principally concerned with matters of agency and practice – that is, in terms of the map on this site, those discourses that land in the upper-right region

- Shared Cognition (Socially Shared Cognition) (John Seely Brown, Allan Collins, Paul Duguid, 1980s) – a descriptive phrase used to span a range of phenomenon involving mutual influence among participants. In more provocative formulations, Shared Cognition is presented as a mode of collective thinking, as individuals come together into grander cognitive systems. In less provocative formulations, Shared Cognition is aligned with Distributed Cognition, Situated Cognition, and/or collaborative engagement. Related constructs include:

- Shared Abstraction (Celia Hoyles, Richard Noss, 1990s) – a phrase coined to highlight the manner in which one’s formal understanding of a concept can be simultaneously abstract and situated – that is, available to be applied across contexts, yet anchored to specific experiences.

- Taken-as-Shared (Paul Cobb, 1990s) – a descriptor applied to different knowers’ understandings of the same notion. Taken-as-Shared is used to highlight that different individuals cannot have identical understandings – because each person’s knowing is rooted in unique sets of personal experiences. Even so, knowers tend to act as though their understandings are fully compatible – that is, those understandings are typically taken to be shared.

- Working Consensus (Erving Goffman, 1950s) – provisional and temporary convergence (i.e., “good-enough” agreement) on the nature of a situation or problem shared by a group of actors. Similar notions include:

- Situated Knowledge (D0nna Haraway, 1980s) – the assertion that every claim to truth is always and already affected by the knower’s history, community, language, values, and intentions. The notion of Situated Knowledge is often associated with Epistemic Relativism (under Rationalism) and/or Postmodern Epistemologies (under Epistemology).

- Social Psychology (Charles Cooley, 1910s) – a domain that studies of one’s thinking, feeling, and acting are affected by the “presence” of others, whether that presence is real or imagined. Types of Social Psychology include:

- Consistency Theory (Self-Consistency Theory) (Fritz Heider, 1970s) – a cluster of Social Psychology theories that share the conviction that one is motivated primarily by desire for consistency across one’s mental abilities – and thus will act in ways to maximize the relationship between performance and self-image

- Consumer Psychology (Consumer Behavior) – a branch of Social Psychology that concerned with making sense of beliefs, emotions, habits, perceptions, and trends among consumers, most often motivated by corporate interests in creating and marketing products that will be seen as desirable. Consume Psychology has been growing prominence with education over recent decades as metaphors of “student as client/consumer” and “institution as service provider” have supplanted more learning-oriented notions.

- Psychological Social Psychology (Gordon Allport, 1950s) – a branch of Social Psychology that emphasizes psychological processes

- Sociological Social Psychology (Gordon Allport, 1950s) – a branch of Social Psychology that places more emphasis on the influence of the collective and the context on the individual than the individual’s influence on larger systems

- Social Representations (Serge Moscovici, 1960s) – values, ideas, beliefs and metaphors that establish social order, orient participants, and enable communications amongst groups and communities. Social Representations must be understood as codes for social exchange.

Commentary

Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses began to press into the field of education in the 1960s, spurred by social movements and academic discussions that foregrounded the collective (and often oppressive) character of knowledge. That historical moment represented a sharp turn in cultural sensibilities around the production and perpetuation of “truth,” as it was made evident that most cultural knowledge was not inscribed in the universe. Rather, it was principally a matter of social accord. The cultural enterprise of formal education was thus implicated in the project of perpetuating such knowledge, and this realization was key in prompting a shift away from seeing schooling in terms of preparing children for adult lives toward seeing schooling as an ethical obligation to involve learners as active participants in (vs. passive recipients of) cultural knowledge.Subdiscourses:

- Appropriation of Knowledge

- Basic Personality

- Behavior Setting Theory

- Boundary Crossing

- Boundary Object

- Boundary-Work

- Consumer Psychology (Consumer Behavior)

- Big “D” Discourse

- Collective Conscience (Common Conscience)

- Continental Philosophy

- Cultural Studies

- Culture

- Discourse Analysis

- Discourse Community

- Discourse Routine

- Discourse Theories (Discourse Studies)

- Discursive Practice

- Discursive Psychology

- Dynamic Social Impact Theory

- Enculturation

- Externalisms

- Horizontal Discourse

- Impact Theory

- Little “d” discourse (Small “d” discourse)

- Object-Based Learning

- Participatory Epistemology (Participatory Theory)

- Postformalism

- Practice Theory (Praxeology; Social Practice Theory; Theory of Social Practices)

- Psychological Social Psychology

- Shared Abstraction

- Shared Cognition (Socially Shared Cognition)

- Situated Knowledge

- Social Impact Theory

- Social Psychology

- Social Representations

- Sociological Social Psychology

- Taken-as-Shared

- Universe of Discourse

- Vertical Discourse

- Working Consensus

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List