AKA

Alternate Education

Alternative Schools Movement

Education Reform Movement

Nontraditional Education

Reform Education

Focus

Approaches that depart from standardized educationPrincipal Metaphors

There are many, many versions of Alternative Education, spanning ranges of sensibilities and ideologies. Consequently, there is no consistent set of associated metaphors. However, with only a few exceptions, varieties of Alternative Education tend to identify a common opponent – namely, conceptions of learning that are rooted in Folk Theories.- Knowledge is … not a thing

- Knowing is … not an internal model of external things

- Learner is … not an insulated and isolated individual

- Learning is … not acquiring, constructing, internalizing, or seeing

- Teaching is … not delivering, conveying, or telling

Originated

Several centuries ago, with the rise of standardized education – but, since the late 1800s as a discernable movementSynopsis

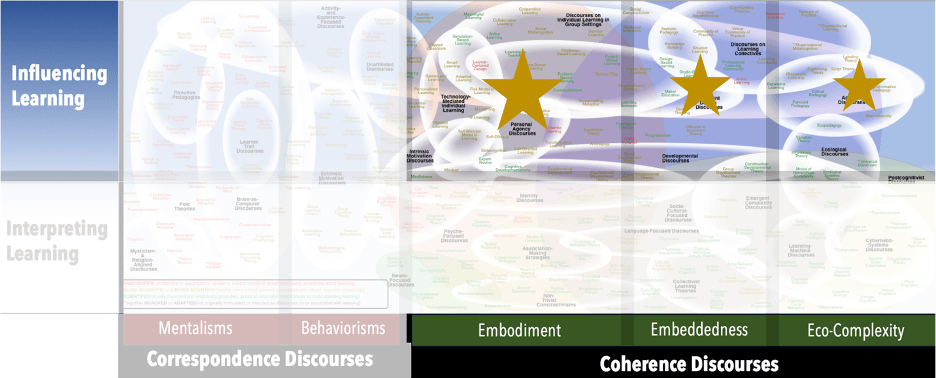

The term “Alternative Education” has been applied to many educational movements, curriculum innovations, and teaching approaches that, considered en masse, are linked only in their rejection of mainstream philosophies and practices. For the most part, specific types of Alternative Education are fitted to discourses that sit in the upper right regions of our map, and many are specifically affiliated with Authentic Learning and Progressivism, with strong links to Activity- and Experience-Focused Discourses (especially Learning Design and Activist Discourses) and approaches that emphasize group process (e.g., Discourses on Individual Learning in Group Settings and Discourses on Learning Collectives). Aligned discourses include:- Systemic Reform (Systemic Improvement) – a relatively recent elaboration of the reformist sensibilities associated with Alternative Education. The notion is subject to context- and purpose-specific interpretations – but, in general terms, it is associated with principles of Complex Systems Research and intended to signal the necessity of simultaneously attending to multiple roles (e.g., students, teachers, administrators), multiple levels of organization (e.g., classroom, schools, jurisdictions, educational systems), and multiple programs and streams (e.g., , arts, sciences, primary, secondary)

- Anti-Schooling Activism (Radical Education Reform) – a political and educational position that might be characterized as a blending of Activist Discourses and Alternative Education. Anti-Schooling Activism is not associated with a singular purpose or well-defined goal, but common aspects revolve around deep aversions to aspects of modern schooling – e.g., its compulsory nature, its monopoly in formal education, its function as a tool of assimilation, and its increasingly ill fit with the “real” world. Many of the discourses described below are examples of Anti-Schooling Activism, including Anarchistic Free Schools, Unschooling, Deschooling, and Free Spaces.

- Humanistic Education (Person-Centered Education) (Carl Rogers, 1960s) – an umbrella category that includes any approach to formal education that is designed to engage the whole learner, attending to bio-physical, intellectual, emotional, and social aspects of one’s being while supporting growth and the development of practical, artistic, and critical competencies. Most of the discourses described below are examples of Humanistic Education, including Montessori Method, Waldorf Education, and Reggio Emilia Approach.

- Friends Schools (Quaker Schools) (first appeared in the early-1700s) – Rooted in the beliefs and practices of Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers), Friends Schools aim to provide both a good academic education and a community-based, spiritually rich character education.

- Pestalozzian (Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, late-1700s) – an adjective applied to a teaching attitude that foregrounds such principles as educating the whole person, dealing with learners compassionately, and positioning education as a means to social and economic betterment. Pestalozzi's perspectives were foundational to Froebelism, the Montessori Method, Waldorf Education, and other movements listed below.

- Head, Heart, Hands (Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, late-1700s) – the threefold admonition to speak to the child's level (Head), be attentive to the child's affective existence (Heart), and to ensure the child's occupations are meaningful (Hands)

- Froebelism (Frobelism) (Friedrich Froebel, 1830s) – a system of early education, and the origin of the Kindergarten movement, founded on the conviction that learners are active and creative, not passive and receptive. Froebelism thus emphasizes well-directed play and other stimulating activities.

- Montessori Method (Maria Montessori, late-1800s) – Positioning the child as an eager learner, and informed by principles consistent with Non-Trivial Constructivisms, the Montessori Method regards education as the release of human potentialities. It is based on close observation of the child and structured within carefully prepared environment to support learner initiative. Defining qualities of such environments include mixed-age classrooms (typically in clusters that span ~3 years), optional sets of study, specialized classroom materials made from natural materials, physical settings scaled to the learner, low teacher-student ratios, and very well-trained teachers. (See also Montessori's Four Places of Development, under Cognitive Developmentalisms.) Associated discourses include:

- Educateurs Sans Frontières (“Educators without Borders”) (Association Montessori Internationale, 2010s) – an organiszation patterned after Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders), consisting of a network of trained Montessori practitioners who support educational initiatives across all age levels in communities around the world with views toward advancing human development and working toward sustainability

- Scientific Pedagogy Group (Association Montessori Internationale, 2000s) – a network of researchers focused on examining and evolving Montessori method.

-

Anarchistic Free Schools (Free Skools; Anarchist Free Schools; Anarchist Pedagogies) (Escuela Moderna; late-1800s) – As might be expected, formal education is a fraught topic among anarchists, who agree on little except there are no universal or generalizable approaches to dismantling or avoiding hierarchical structures, authoritarian tendencies, and institutional settings. Against this backdrop, Anarchistic Free Schools are autonomous grassroots efforts, involving collectives working to create educational settings to share skills and expertise.

- Scout Method (Robert Baden-Powell, 1910s) – a form of Non-Formal Learning (see In-/Non-Formal Learning) focused on the characters and dispositions of children and adolescents, and structured around outdoor and interactive challenges

- Waldorf Education (Anthroposophical Education; Steiner Pedagogy) (Rudolf Steiner, 1910s) – Associated with Holistic Education (see below), Waldorf Education is structured around the principle that “all education is self-education” as it aims to support the development of all aspects of the learner – academic, artistic, athletic, and practical. While typically oriented by state-mandated curricula, individual teachers are permitted considerable autonomy around matters of topics of study, pedagogical methods, and classroom structure. Associated discourses include:

- Anthroposophy (Rudolf Steiner, 1910s) – meaning “wisdom of the human being,” the study of being human – development, learning, purpose, and so on – with a strong emphasis on growth as spiritual-scientific beings and life-long learners withphysical existences

- Camphill Communities (Camphill Movement) – residential schools based on the principles of Anthroposophy that are designed to support the educations and daily lives of adults with special needs

- Curative Education (Rudolf Steiner, 1920s) – a pedagogical attitude designed for individuals who are dealing with issues that complicate education, such as a physical pathology, ill health, or a psychological problem. Curative Education is organized around two principles: observation (of the child’s being and becoming) and love (as the motivation and means of engagement).

- Eurythmy (Visible Song; Visible Speech) (Rudolf Steiner, Marie von Sivers, 1910s) – movement of the body to music and/or the human voice for the purpose of enabling one’s creative and expressive capacities

- Modern School (Ferrer Modern School) (Francisco Ferrer, 1910s) – Originating after the execution of Francisco Ferror, a social anarchist, the Ferrer Modern School is a libertarian day school that supports children’s play and advances radical politics while eschewing planned pedagogy and imposed curricula.

- Holistic Education (Helping Model) (Jan Christiaan Smuts, 1920s) – Both a philosophy and a movement, Holistic Education is concerned with the integrated development of all aspects of the learner (frequently expressed in terms of “mind, body, and spirit,” but sometimes emphasizing social/interpersonal relationships and cultural/democratic sensibilities).

- Summerhill School (A.S. Neill, 1920s) – Oriented by the notion that the school should be made to fit the child (not vice versa), Summerhill School is a boarding school in Suffolk, UK that is organized as a one-person-one-vote democracy that includes all community members. Structured according to the principle of “Freedom, not Licence,” citizens are permitted to do as they please, as long as their doings do not cause harm to others.

- Reggio Emilia Approach (Loris Malaguzzi, 1940s) – Named after the region in Italy in which it began, the Reggio Emilia Approach is focused on preschool and primary school levels. It has much in common with Inquiry-Based Learning and Project-Based Learning, especially around the principle that young children should be invited to present their ideas through any of their many means of self-expression (e.g., painting, writing, singing, drama). Aligned with Non-Trivial Constructivisms, school settings foreground notions of respect, community, exploration, play, and responsibility. Associated constructs include:

- 100 Languages (The Hundred Languages of Children) (Loris Malaguzzi, 1940s) – a double metaphor intended to highlight both the vastness of potential (“100”) and the variety of possibilities (“languages”) in every child

- Reggio Project – an explorative engagement of small groups of children of varied abilities and needs of a topic of shared interest and uncertainty that fosters creative thinking and problem-solving abilities

- Third Teacher (Loris Malaguzzi, 1940s) – the environment, considered alongside children themselves (the first teacher) and adults (the second teacher). The environment should be both beautiful and functional, designed to support and engage children.

- Freedom Schools (1950s) – Original part of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, Freedom Schools were implemented as a temporary measure to provide free education to African American children that was on par socially, politically, and economically with the public education provided to other American children.

- Open Classroom (1960s) – Rejecting segregations based on age, ability level, grade, and gender, the Open Classroom typically involves a large group of learners and several teachers. Much of the activity is accomplished in small groups that are selected according to interests, subject areas, and skill levels.

- Open-Space School (Open-Area Classroom) (1960s) – Rooted in the same convictions as the Open Classroom, an Open-Space School is organized in large open areas (i.e., few or no physical classroom walls) that are intended to foster movement of teachers and learners according to need and interest.

- Sudbury School (Daniel Greenberg, 1960s) – Named after the Sudbury Valley School in Framingham, MA, a Sudbury School has two defining qualities: (1) everyone is treated equally, and (2) all authority is rooted in democratic process. Students thus have complete responsibility for their own educations. There is no predefined curriculum and no prescriptive teaching.

- Cradle School (Cradle Education; Cradle Teaching) (various, 1970s) – a range of formal educational experiences aimed at children from birth to age 5 years (i.e., pre-Kindergarten) – principally by supporting parents, but also through direct in-person and on-line offerings

- Free School Movement (Democratic Free Schools; New Schools) (Jonathan Kozol; 1970s) – Strongly influenced by Summerhill School, this movement is focused on offering alternatives to traditional schooling. There are wide variations among free schools, but they tend to align around matters of self-governance (typically through participatory democracy) and choice (i.e., of parents for their children, and of children for topics and pacing).

- Homeschooling (Home Education; Elective Home Education) (ancient roots; a marked resurgence in the 1960s as a response to Standardized Education; emerging as a formal academic discourse in the 1970s)– This umbrella notion encompasses a wild variety of approaches to and emphases in formal learning, which are linked only by a decision to conduct most or all of a child’s education at home or in other non-school settings. Associated constructs include:

- Microschools (Outsourced Homeschooling) (2020s) – a term applied to a range of organizations that subject to a wide range of regulations and structures, depending on locations and orientations. Microschools can cover grades K–12 and typically have fewer than 20 students.

- Open Learning (1970s) – Incorporating many of the sensibilities described above, Open Learning is typically associated with educational approaches that attend to learner difference (in experience, interest, development, etc.) and the emphasis learner autonomy (through, e.g., self-determination, self-regulation, and interest-guided learning). (Note: Another prominent meaning of Open Learning has recently emerged, having to do with free sharing of educational materials.)

- Unschooling (John Holt, 1970s) – While subject to much variation in interpretation, Unschooling might be considered in terms of contrasts with formal schooling: informal, in natural settings, unscheduled, involving much play alongside everyday responsibilities, oriented by personal interests, amongst persons of different ages and expertise, free of preformulated expectations and grading structures, and so on.

- Deschooling (Ivan Illich, 1970s) – Currently in popular use among proponents of Homeschooling and Unschooling, the word Deschooling was coined to describe the breaking out of habits and mindsets instilled by schools.

- Learning Web (Ivan Illich, 1970s) – a means of Deschooling (see above) that involves affording the tools and operations used in learning, means to draw on one another’s skills, and means to connect with peers who have similar interests

- Personal Curriculum Design (Maryland Plan) (D. Maley, 1970s) – a schooling structure through which learners make their own decisions on curriculum topic and learning methods

- Free Spaces (Sara Evans, Harry Boyte; 1980s) – physical and/or conceptual “spaces” that are deliberately insulated from the influences of dominating authorities. The notion was first developed to characterize the meeting “places” of a range of social and activist movements (e.g., union halls, lesbian feminist communities, etc.). It has been more recently aligned with Anarchist Free Schools and the Free School Movement, affording a rationale for defining and protecting Free Spaces in more traditional educational settings.

- Slow Learning (Slow Education; Slow Schooling) (associated with the “Slow Movement,” Carlo Petrini, 1980s) – an explicit response to perceived-to-be-overstuffed curricula and associated achievement examinations. Slow Learningproblematizes those aspects of schooling that focus on time pressures and standardization – and, thus, matters of deep engagement, lingering, and choice figure prominently in the movement.

- Genius Hour (Passion Project) (frequently attributed to Google, 2000s) – Oriented by the principle that learning will happen if learners are permitted to pursue something that is personal and compelling, Genius Hour is time set aside in the school day to allow students to engage with topics of their own choosing and in manners that can depart radically from the expectations of traditional formal education.

- Small Schools Movement (Small Schools Initiative) (Deborah Meier; 2000s) – Oriented by the conviction that smaller school populations are better for social connection and more opportunity for individual attention – and therefore more conducive to rich and robust learning – the Small Schools Movement recommends that high schools be kept under 200 students.

- Small Learning Community (School-Within-A-School) (2000s) – Oriented by a desire for more personalized learning, a Small Learning Community is a model for subdividing large school populations in smaller, semi-autonomous clusters of students and teachers.

- Expeditionary Learning (Outward Bound) (Kurt Hahn, 2000s) – Inspired by the work of Kurt Hahn, the term Expeditionary Learning is applied to schools in which rigorous study is embedded in “expeditions” – i.e., extended investigations of compelling topics in the real world that lead to public presentations. Although predating Deeper Learning, the sensibilities and aims of Expeditionary Learning are very similar.

Commentary

Beyond signaling some of the common themes and prominent discourses encountered across most varieties of Alternative Education (as summarized above), given the differences in their historical and ideological influences, there is little point in attempting global commentary. That said, there is a tendency across most of the above discourses toward “learner-centeredness” – which, while not in itself troublesome, can snowball in pernicious ways, including:- “Know Your Learner(s)” (various, 1980s) – an imperative for teachers that was originally aligned with the realization that the most impactful “factor” in one’s learning is what one already knows – which was an insight expressed in reference to the learning of specific subject matters. It has since morphed into an insistence that good teaching is dependent on a detailed knowledge of not just each student’s personal achievements and personality traits (often devolving to constructs associated with Learner Trait Discourses), but also each person’s experiential history, family life, ethnic background, peer relationships, socio-economic situation, and community life. Conspicuously (and ironically) absent across most of the more-recent iterations of the notion is the teacher’s obligation to know the subject matter they are to teach.

Authors and/or Prominent Influences

John Dewey; A.S. Neill, Maria MontessoriStatus as a Theory of Learning

It is common among specific types of Alternative Education to identify with Non-Trivial Constructivisms and/or Socio-Cultural Theory. However, none can be appropriately described as a theory of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Most, if not all, varieties of Alternative Education can be appropriately described as specific perspectives on teaching, typically driven by combinations of specific theoretical and ideological convictions.Status as a Scientific Theory

It would be stretch to use the word “scientific” to describe any single model of Alternative Education. While most draw directly on defensible theories of learning and some are based on systematic observation of learners (e.g., Montessori Method), almost every variety is more defined by its ideological allegiance than its scientific commitment.Subdiscourses:

- Anarchistic Free Schools

- Anthroposophy

- Anti-Schooling Activism (Radical Education Reform)

- Camphill Communities (Camphill Movement)

- Cradle School (Cradle Education; Cradle Teaching)

- Curative Education

- Deschooling

- Educateurs Sans Frontières

- Eurythmy (Visible Song; Visible Speech)

- Expeditionary Learning

- Free School Movement

- Free Spaces

- Freedom Schools

- Friends Schools (Quaker Schools)

- Froebelism (Frobelism)

- Genius Hour (Passion Project)

- Head, Heart, Hands

- Holistic Education (Helping Model)

- Humanistic Education (Person-Centered Education)

- 100 Languages (Hundred Languages of Children)

- Homeschooling (Home Education; Elective Home Education)

- “Know Your Learner(s)”

- Learning Web

- Microschools (Outsourced Homeschooling)

- Modern School (Ferrer Modern School)

- Montessori Method

- Open Classroom

- Open Learning

- Open-Space School (Open-Area Classroom)

- Personal Curriculum Design (Maryland Plan)

- Pestalozzian

- Reggio Emilia

- Reggio Project

- Scout Method

- Scientific Pedagogy Group

- Slow Learning (Slow Education; Slow Schooling)

- Small Learning Community (School-Within-A-School)

- Small Schools Movement

- Sudbury School

- Summerhill School

- Systemic Reform (Systemic Improvement)

- Third Teacher

- Unschooling

- Waldorf Education (Anthroposophical Education; Steiner Pedagogy)

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2023). “Alternative Education” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List