Focus

Tethering all truth claims to sound, rational argumentPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … scope of possible interpretation

- Knowing is … considered thought and action

- Learner is … a thinker

- Learning is … reasoning

- Teaching is … challenging (to think)

Originated

Ancient (but the most influential formalized versions began to appear in the 1600s)Synopsis

Rationalism positions reason as both the source and the measure of sound knowledge – that is, Rationalism is the belief that valid knowledge is based in reason without the aid of the senses. It begins with the assumption that reality has a logical structure. Hence, all versions of Rationalism privilege formal, deductive logic. Some versions also permit other Modes of Reasoning, provided the reasoner is explicitly aware of the mode being used and the purpose for its application. However, while the frame does accept that the senses are necessary for actual knowledge, information from the senses is to be doubted. That is, all sensory-based interpretations must be rationally defensible. Rationalism is prominently associated with:- Analytic Philosophy – an approach to formal argument that is framed by an attitude of Analysis (see Modes of Reasoning) – that is, the logical reduction of a claim to truth to its basic premises. Analytic Philosophy is associated with Rationalism. (Contrast: Analytic Science, under Empiricism.)

- Argumentation Theory (Argumentation) – the study of how assertions are supported or disputed. Argumentation Theoryspans topics of logic, inference, debate, persuasion, negotiation, collaboration, and social conventions.

- Logic – formally: the study and application of systems of rules used to assess the validity of conclusions that are based on sets of initial propositions.

- Reliabilism (Reliabilist Epistemology) – the perspective that a belief, assertion, or conclusion is justified if the process used to generate it is reliable. (Contrast: Evidentialism, under Empiricism.)

- Logical Pluralism – the perspective that there are multiple “correct” forms of argumentation – depending, for example, on the phenomenon under consideration and the context of the discussion.

- Binary Logic (Bivalent Logic; Boolean Algebra; Boolean Logic; Two-Valued Logic) – any logic concerned with absolute true/false (1/0; Y/N; ON/OFF) statements that makes use of limited operations (typically: AND, OR, NOT) to calculate the truth value of assertions

- Fuzzy Logic (Lotfi Zadeh, 1970s) – a version of logic in which membership in a set isn’t a matter of yes/no (i.e., 1/0; T/F), but of degrees – that is, a phenomenon can both belong to a set to some degree and not belong to some degree. While Fuzzy Logic departs from classic logic, it is in many ways a better model of human thinking — by, for example, allowing for more exemplary instances (e.g., robins are more bird-like than ostriches) and partial membership (e.g., bats are somewhat bird-like)

- Many-Valued Logic (Multiple-Valued Logic; n-Valued Logic) – an umbrella category that collects any formal system used to calculate the validity of assertions in which there is a finite number of more than two possible truth values (e.g., YES, POSSIBLY, NO)

- Modal Logic – Definition 1: Broadly defined, Modal Logic is a category of formal logics that introduce notions of possibility, permission, temporality, belief, and other contingencies. These logics include:

- Modal Logic – Definition 2: narrowly defined, a type of logic that explores the field of possibility when propositions are stated in terms of requisites (“It is necessary that …”) and prospects (“It is possible that …”)

- Deontic Logic – from Greek dei “it is necessary,” a type of logic that explores fields of possibility when propositions are expressed in terms of obligation (“It is obligatory that …”) and permission (“It is permitted/forbidden that …”)

- Doxastic Logic – from Ancient Greek doxasía “conviction,” a type of logic in which the propositions are stated in terms opinions and beliefs (“Person A believes that …”)

- Imperative Logic – a type of logic in which the propositions are instructions or directives. It’s a contested field, with little or no consensus on core aspects.

- Temporal Logic (Arthur Prior, 1950s) – a type of logic that deals with propositions that are qualitied in terms of time – e.g., “It has always been the case that …”, “It will always be the case that …”, “It was the case that …”, “It will be the case that …”

- Nous (Plato, c. 400 BCE) – the highest form of reason, which was seen to enable one to grasp the fundamental and permanent principles of reality

- Natural Law Theory (Ancient Greek Stoicism, 300s BCE) – the conviction that there are principles of personal, social, and cultural action that are woven into the fabric of reality. It is assumed that rational thought is suffient to discern these principles.

- Cartesianism (Rene Descartes; 1600s), which deploys deductive reasoning (assumed to be gifted from an infallible God) to build on assumed-to-be inarguable-truths (“innate ideas”) to generate imagined-to-be-unimpeachable assertions. Associated constructs include:

- Cogito (cogito ergo sum) (René Descartes, 1600s) – abbreviated from René Descartes’ formulation cogito ergo sum (usually translated as “I think, therefore I am,” but argued by many to be more appropriately phrased in the less causal terms of “I think, I am”), Cogito is a reference to the project of Rationalism to derive all truth from self-evident propositions.

- Method of Doubt (Cartesian Doubt; Method of Systematic Doubt) (René Descartes, 1600s) – an approach to argument and proof that proceeds by discarding any belief or assertion that presents the slightest reason for doubt (Contrast: Positivism)

- Rational Decision Making (various; date unclear, but prior to the 1900s)– a step-by-step model that is asserted to lead to soundly reasoned, evidence-based conclusions. There are multiple models that vary in minor ways. Most versions include the following sequential elements: Identifying the problem; Setting the criteria for decisions; Gathering relevant information; Distilling and verifying information; Designing a course of action; Repeat if necessary. (Contrast: Scientific Method, under Empiricism.)

- Anti-Realism (Michael Dummett; 1960s) – which, as the name suggests, begins by rejecting the “realist” assumption that truths are literal depictions of an external, independent reality. Within Antirealism, the truth of an assertion is determined through internal logic mechanisms. (Notably, some of those mechanisms vary considerably from the tenets and constraints of classical logic.)

- Lay Epistemic Theory (Arie W. Kruglanski, 1980s) – a perspective on the sources of and confidence in one’s personal knowledge, which is defined in terms of assemblages of formal propositions. Operating similarly on both conscious and unconscious levels, propositions are seen to go through rule-based stages of hypothesizing, testing, and inference-generating.

Commentary

Most commentaries on Rationalism are focused on the version articulated by René Descartes in the early 1600s. In his Cartesianism (see above), he argued vigorously that eternal truths could be attained by reason alone, independent of the senses. Many aspects of Cartesianism endure in popular thought (e.g., his “Cogito, ergo sum” and his “Method of Doubt”), but perhaps the conclusion with the greatest staying power is his dualism of body and mind/soul, seen as independent and irreducible. Many recent criticisms focus on the fact that Rationalism is a closed system of reasoning, which necessarily renders it insufficient to account for this universe – which, according to most, is an open system. In quite a different vein, Rationalism has been criticized for its ready associations with discourses that share its emphasis on mental activity, even though many lack its commitment to logic – including:- Nominalism (ancient; revived by Thomas Hobbes, 1650s) – the notion that abstract principles and universal laws are not aspects of reality, but human constructs that exist only as names. These names collect useful ways to think about the physical universe, but they do not (and cannot) capture that universe.

- Presentism – a term with many definitions. Among those most relevant to discussions of knowledge, learning and teaching, Presentism might be understood as (1) the perspective that only what is present actually exists, or (2) the uncritical habit of interpreting events, past and present, in terms of contemporary sensibilities.

- Psychologism (Johann Eduard Erdmann, 1890s) – an umbrella notion that can be applied to any discourse in which human thought is positioned as the basis of knowledge, meaning, and/or logical truths

- Relativism – applies to the conviction or opinion that “facts” within a specific domain are dependent on the knower’s perspective and/or the knower’s context. Specific variations include:

- Epistemic Relativism (Alethic Relativism; Cognitive Relativism; Factual Relativism) – an extreme version of Relativism that asserts that all facts and truths are dependent on the knower

- Cultural Relativism – a version of Relativism that focuses on one’s culture as a means to make sense of one’s version of truth, arguing that cultures should not be judged against each other

- Solipsism – the view that one can only be certain of the existence of one's own mind – that is, everything else (e.g., other minds, a physical world) might not exist

- Subjectivism – refers to a variety of perspectives sharing the premise that one’s truths are entirely rooted in one’s unique set of experiences. Extreme versions, such as Cartesianism (see above), assert that one’s thoughts are the only unquestionable facts of one’s being.

- Universalism – the perspective that aspects of human perception, thought, belief, and action are essential to the species – that is, universal (to humans). On the surface, Universalism might appear the opposite of Relativism. However, their deep similarity is revealed in the recognition that the Relativism asserts itself applicable to all humans. It is a universalist discourse.

Authors and/or Prominent Influences

René Descartes; Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz; Baruch Spinoza; Immanuel KantStatus as a Theory of Learning

Rationalism is a theory of knowledge and knowledge production, and it is typically discussed at the level of entire fields of study. It has also been applied to individual learning, and many contemporary learning theories assume that the identification of assumptions, formulation of principles, and development of logically defensible arguments is a fitting model for formal learning. For that reason, it is fair to say that Rationalism has been embraced by many educators as a theory of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Often, when Rationalism is invoked as a perspective on learning in education, it is in contexts focusing on influencing learning – in particular, through clear articulation of assumptions and carefully structured arguments. Concisely, then, within education, Rationalism is frequently engaged as a theory of influencing learning.Status as a Scientific Theory

Owing to the very different ways Rationalism has been interpreted and applied within education, we have not afforded it full scientific status. Many treatments are simply inattentive to assumptions and figurative frames. In fact, somewhat ironically, some treatments are inattentive to empirical evidence demonstrating issues with their interpretations.Subdiscourses:

- Analytic Philosophy

- Anti-Realism

- Argumentation Theory (Argumentation)

- Binary Logic (Bivalent Logic; Boolean Logic; Two-Valued Logic)

- Cartesianism

- Cogito (cogito ergo sum)

- Cultural Relativism

- Deontic Logic

- Doxastic Logic

- Epistemic Relativism (Alethic Relativism; Cognitive Relativism; Factual Relativism)

- Fuzzy Logic

- Imperative Logic

- Lay Epistemic Theory

- Logic

- Logical Pluralism

- Many-Valued Logic (Multiple-Valued Logic; n-Valued Logic)

- Method of Doubt (Cartesian Doubt; Method of Systematic Doubt)

- Modal Logic

- Natural Law Theory

- Nominalism

- Nous

- Presentism

- Psychologism

- Rational Decision Making

- Relativism

- Reliabilism (Reliabilist Epistemology)

- Solipsism

- Subjectivism

- Temporal Logic

- Universalism

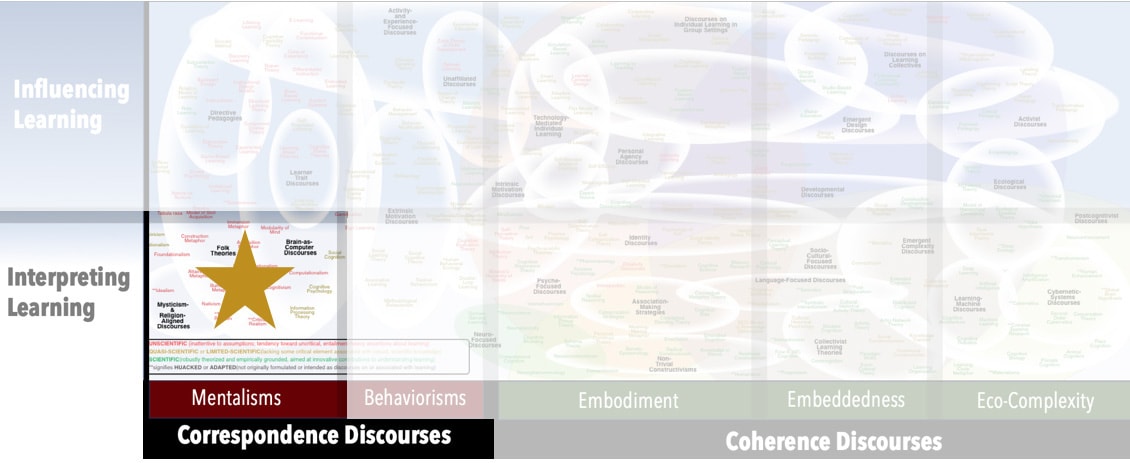

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2023). “Rationalism” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List