AKA

Evidentialism

Focus

Tethering all truth claims to physical evidencePrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … all demonstrable truths

- Knowing is … experience-based awareness

- Learner is … an experiencer, inquirer

- Learning is … deriving truth from experience

- Teaching is … formatting experiences

Originated

Ancient (but the most influential formalized versions began to appear in the 1500s)Synopsis

Empiricism is more commonly understood as a theory of knowledge than a theory of learning, but the distinction is often blurred in discussions of education. Empiricism states that knowledge comes from sensory experience, and thus emphasizes the role of experience and evidence. The “hard” version of Empiricism is associated with rigorous scientific research ...- Evidentialism (Evidentialist Epistemology) – the perspective that a belief, assertion, or conclusion is justified only if it has supporting evidence. (Contrast: Reliabilism, under Rationalism.)

- Evidence-Based (Data-Based; Research-Based; Scientific) – an adjective applied to any claim supported by evidence drawn from replicable and/or broad-based data sources. The term is common in education, with usages that include evidence-based decisions, evidence-based instruction, Evidence-Based Learning (see Visible Learning), and evidence-based school improvement. (See, also, our more detailed definition of “Scientific,” as the term is applied on this site.)

- Idiographic (Wilhelm Windelband, 1890s) – from the Greek idios “one’s own,” a mode of research that tends toward specificity and in which subjectivity and contingency are foregrounded. The Humanities (under Humanisms) are typically cited as illustrative of an Idiographic attitude.

- Nomothetic (Wilhelm Windelband, 1890s) – from the Greek nomothetes “lawgiving,” an attitude toward research that tends toward generalization and in which objectivity and replicability are emphasized. The natural sciences are typically cited as illustrative of a Nomothetic attitude.

- Analytic Science – the approach to knowledge generation and verification that is framed by an attitude of Analysis – that is, the logical reduction of a phenomenon to fundamental elements (see Modes of Reasoning). In the extreme interpretation, Analytic Science assumes that all phenomena can be understood in terms of logical and/or causal relations – which, ultimately, can be reduced to basic particles and fundamental laws. (Contrasts: Analytic Philosophy, under Rationalism; complexity perspectives, discussed in Complex Systems Research)

- Aristotelianism (Aristotole, 300s BCE) – subject to quite varied definitions that tend to agree on two key elements: the truth is out there, and it can be reached through careful definition, observation, and demonstration

- Baconian Method (Francis Bacon, late-1500s) – an inductive (see Modes of Reasoning) method of scientific study that involves inferring general principles from specific instances that are studied under controlled conditions. The broad goal of the Baconian Method is to generate “laws” (i.e., principles that are accurate across any instance of a phenomenon under study) that can be used to infer causality.

- Logical Empiricism (Logical Positivism; Neopositivism) (Vienna Circle, early 1900s) – an attempt to mesh principles of mathematical logic with the conviction that sensory experience is the basis of knowledge, based on two main principles: (1) statements made in everyday language can be parsed into discrete units of meaning; (2) only statements that can be verified through direct experience or logical proof can be deemed truly meaningful

- Nomology – an attitude toward scientific inquiry focused on the study of natural laws, oriented by a desire for (or, perhaps, a faith in) causal models and explanations. Associated discourses include:

- Covering-Law Model (Deductive-Nomological Model; Hempel’s Model; Hempel–Oppenheim Model; Popper–Hempel Model) (Carl Gustav Hempel, 1950s) – the perspective that a phenomenon is scientifically understood only if it can be predicted by using scientific laws

- Phenomenalism (John Stuart Mill, mid-1800s) – an extreme version asserting that all physical forms are reducible to mental forms – that is, in essence, that physical objects are constructed out of one’s experiences

- Positivism – the attitude that the highest standard of certainty is scientific fact, which can only be derived through direct experiences of phenomena. Such experience typically includes observation of and experimentation on the phenomenon of interest, coupled with reasoned argument that is attentive to what is known about surrounding and related phenomena.

- Pragmatism (Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, John Dewey, late-1800s) – an integration of basic insights of experience-based Empiricism with thinking-based Rationalism

- Probabilism – an umbrella category that reaches across perspectives that (1) accede that empirical science will never have the measuring accuracy or computing power to predict complex phenomena with any useful precision, and so (2) turn to probability and statistics as the most useful and reliable means to discern facticity, make defensible choices, and predict futures. Associated discourses include:

- Probabilistic Functionalism – the suggestion that agents’ perceptions and actions are essentially probabilistic – that is, selected according to probable success

- Radical Empiricism (William James, early 1900s) – the position that reality consists of pure experience

- Scientific Pluralism (Jerry Fodor, Paul Feyerabend, 1970s) –the realization that there can be no singular frame for and no one-size-fits-all approach to scientific inquiry, at the same time as there can be broad agreement on the intentions of science

- Consilience (Concordance of Evidence; Convergence of Evidence) (coined by William Whewell, 1840s; developed by E.O. Wilson, 1990s) – the conviction that empirical evidence from diverse sources should converge on the same conclusions, bolstering those conclusions in the process (that is, rendering them more “scientific”). Consilience is founded on the assumption that the same fundamental laws underlie all existence. Related discourses include:

- Tektology (Alexander Bogdanov, 1920s) – a proposed universal science. Tektology was an attempt to unify the physical, biological, and social sciences by reframing them as systems of relationships, which entailed attending to the structures and dynamics of systems. Tektology was an important precursor to Complex Systems Research.

- Convex Tinkering (Nassim Taleb, 2010s) – a method of scientific inquiry involving low-risk, high-reward experimentation. By leveraging uncertainty to maximize upside while minimizing downside, Convex Tinkering is asserted to outperform directed research.

- Epistemic Humility – a conscious awareness that fully objective observations and conclusions are impossible, because all scientific data are fitted to and filtered through human perceptual systems

- Pasteur’s Quadrant (Donald Stokes, 1990s) – a matrix used to classify scientific inquiries, produced by placing “search for fundamental understanding” on the vertical axis and “relevance for immediate use” on the horizontal axis. Three distinct classes of research are identified:

- Use-Inspired Basic Research – scientific research concerned with both the search for fundamental understanding and relevance for immediate use

- Pure Applied Research – scientific research concerned with relevance for immediate use but unconcerned with the search for fundamental understanding

- Pure Basic Research – scientific research concerned with the search for fundamental understanding but unconcerned with relevance for immediate use

- Rules of Correspondence (Correspondence Rules) – the implicit assumptions, explicit criteria, linguistic tactics, and formal strategies employed to link or align observations with theories/concepts

- Scientific Method has a range of meanings that coalesce around the project of Empiricism to develop increasingly powerful and useful interpretations of phenomena. Varying somewhat from one branch of science to another, common aspects of the Scientific Method across all domains are careful observation and rigorous skepticism. Within branches of inquiry that involve experimentation, the Scientific Method is typically defined to include the formulation of hypotheses, conducting of controlled interventions, and generation of replicable results. In popular terms – and especially prominent in contemporary school science – the Scientific Method is often reduced to a simplistic and rigid, step-by-step procedure that more resembles a recipe than engaged inquiry. (Contrast: Rational Decision Making, under Rationalism.)

- Scientific Rationality – sometimes considered synonymous with Positivism, but more often used to describe an attitude – that is, as a reference to the qualities and standards associated with empirical inquiry (which, notably, vary across academic domains that claim to be oriented by a Scientific Rationality)

- Science Studies (Maria Ossowska, Stanislaw Ossowski, 1930s) – a research domain concerned with understanding the social, historical, political, and philosophical dimensions and entailments of modern science. The field is sometimes described as a branch of Cultural Studies (see Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses).

- Science, Technology, and Society (Science and Technology Studies; STS; STSC) (1960s) – an interdisciplinary domain concerned with the effects of modern science (and the technologies it has enabled) on society and culture

- Technoscience (Gaston Bachelard, 1950s) – the study of the interdependent interactions of technology and Empiricism. Focused elaborations include:

- Feminist Technoscience – a domain concerned with entanglements of gender (and other identity markers) and Technoscience, oriented by the conviction that Empiricism and technology are equally accountable for what they enable and constrain

Commentary

Of course, the major problem with the construct of “scientific knowledge” that sits at the core of Empiricism is separating “science” from “non-science”:- Demarcation Problem – the question of how one might tell the difference between science and non-science

- Bad Science – an informal but common term used to describe flawed, misleading, or unethical scientific practices across academic, journalistic, and public discourse. Bad Science can refer to a range of issues – including, for example poor methodology, misinterpretation of data, bias or conflicts of interest, and/or fraud or misconduct.

- Falsifiability (Refutability) (Karl Popper, 1930s) – a proposed solution to the Demarcation Problem (see above) – namely, that one way to separate “science” from “non-science” is that, to be considered scientific, a claim must be subject to Falsifiability. That is, there must be potential to prove it wrong or incomplete using empirical methods. If there is no potential to prove a claim to be lacking, it is not properly scientific. Associated methods include:

- Hypothetico-Deductive Method (Mathematico-Deductive Method) – a strategy for testing falsifiable hypotheses, by comparing predictions to empirical observations

- Utilitarianism (Jeremy Bentham, early 1800s) – a worldview that might be said to operate on the maxim, “The greatest good for the greatest number.” That is, an act is justified if it maximizes pleasure or benefit. The same premise underlies the following discourses:

- Eudemonism – either (1) the perspective that what brings happiness (“eudemonia”) is what is good, or (2) the belief that people will act in ways that bring them happiness. Utilitarianism is a Eudemonism in the first sense; Psychoanalytic Theories, Humanisms, and Behaviorisms are Eudemonisms in the second sense.

- Hedonism – the doctrine that pleasure is inherently good – and, thus, the pursuit of pleasure is appropriate and good

- Hedonistic Psychology – a descriptor applied to any theory that suggests that pursuing pleasure and avoiding pain are the only major motivations for human behavior

- State-Specific Science (Charles Tart, 1970s) – oriented by a recognition that highly intelligent people can reject science, the suggestion that it might be appropriate to consider multiple conceptualizations of that are fitted to various states of consciousness

- Quasiscience – variously defined, but on this site used to describe perspectives that meet some (but not all) our stated criteria for scientific knowledge. This meaning is based on definitions of “quasi” that have to do with “resemblance due to possession of certain attributes” and “nearly; not far from.”

- Pseudoscience – claims of scientific knowledge that are founded on methods that are not entirely consistent with broadly accepted conceptions of the Scientific Method (see above). Prominent shortcomings in this regard include claims based on assumptions that are unstated or unproven, assertions that are not open to evaluation by other experts or that are framed in ways that render them untestable, and unproven claims that are inconsistent with evidence-based knowledge. Associated notions include:

- Not Even Wrong (Wolfgang Pauli, 1940s) – a description of a claim that is asserted to be scientific but that cannot be rigorously assessed

Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Aristotle; John Locke; Francis Bacon; George Berkeley; David HumeStatus as a Theory of Learning

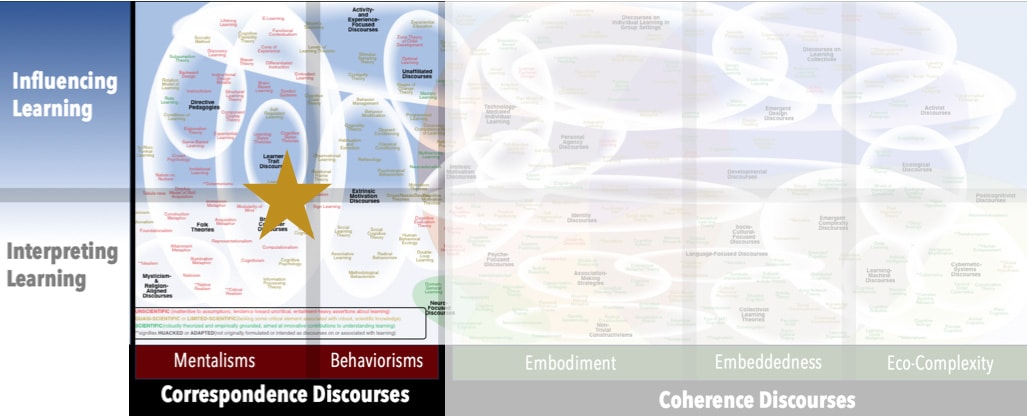

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge and knowledge production, and it is typically discussed at the level of entire fields of study. It has also been applied to individual learning, and many contemporary learning theories assume that the exploratory, sense-making activities of young learners are essential empirical – that is, they are very much processes of gathering, integrating, and generalizing from experiences. For that reason, it is fair to say that Empiricism has been engaged by many educators as a theory of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Often, when Empiricism is invoked as a perspective on learning in education, it is in contexts focusing on influencing learning – in particular, through active, experience-focused, exploration-oriented activities. Concisely, then, within education, Empiricism is frequently engaged as a theory of influencing learning.Status as a Scientific Theory

It might seem circular to argue that Empiricism is scientific. However, given the differences in meaning between empiricist and empirical, we have not afforded it full scientific status. Many versions and treatments of Empiricism are simply inattentive to assumptions and figurative frames. In fact, somewhat ironically, some treatments are inattentive to empirical evidence demonstrating issues with their interpretations.Subdiscourses:

- Analytic Science

- Aristotelianism

- Bad Science

- Baconian Method

- Consilience (Concordance of Evidence; Convergence of Evidence)

- Convex Tinkering

- Covering-Law Model (Deductive-Nomological Model; Hempel’s Model; Hempel–Oppenheim Model; Popper–Hempel Model)

- Demarcation Problem

- Epistemic Humility

- Eudemonism

- Evidence-Based (Data-Based; Research-Based; Scientific)

- Evidentialism (Evidentialist Epistemology)

- Falsifiability (Falsification; Refutability)

- Feminist Technoscience

- Hedonism

- Hedonistic Psychology

- Hypothetico-Deductive Method (Mathematico-Deductive Method)

- Idiographic

- Logical Empiricism

- Nomology

- Nomothetic

- Not Even Wrong

- Pasteur’s Quadrant

- Phenomenalism

- Pragmatism

- Probabilism

- Probabilistic Functionalism

- Pseudoscience

- Pure Applied Research

- Pure Basic Research

- Quasiscientific

- Radical Empiricism

- Rules of Correspondence (Correspondence Rules)

- Science Studies

- Science, Technology, Society (Science and Technology Studies; STS; STSC)

- Scientific Method

- Scientific Pluralism

- Scientific Rationality

- State-Specific Science

- Technoscience

- Tektology

- Use-Inspired Basic Research

- Utilitarianism

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2025). “Empiricism” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List