AKA

Differentiated Learning

Differentiated Task Structures

Differentiation

Focus

Adapting teaching practices to learners’ diverse styles and needsPrincipal Metaphors

- Knowledge is … object, commodity, goal, information

- Knowing is … mastering knowledge

- Learner is … a gatherer (individual)

- Learning is … acquiring, discovering/uncovering, attaining, inputting, processing, making sense

- Teaching is … delivering, facilitating, guiding, leading

Originated

1990sSynopsis

Differentiated Instruction is a teaching emphasis intended to meet the varied learning needs of all students. Most of its discussion is focused on diversities asserted by Learning Styles Theories, Cognitive Styles Theories, Personality Types Theories, and Developmental Discourses, but attention is also given to socio-cultural sources (e.g., socioeconomic status, language, culture) and biologically rooted differences (e.g., gender, brain injuries). Concisely, Differentiated Instruction is oriented by the conviction that learning is maximized when the instructor personalizes the content, tasks, assessments, and/or context, based on a diagnosed learner profile. Associated discourses include:- Differentiated Assessments – Associated with Differentiated Instruction, Differentiated Assessments refer to any strategy developed, adopted, or adapted by a teacher to make sense of each individual student’s current level of mastery and consequent needs.

- Differentiated Teaching – a broader, less-prescriptive version of Differentiated Instruction. The term can be applied to any effort to adjust educational experiences to learners. Most often, Differentiated Teaching refers to ensuring that learners are offered varied starting points (or the opportunities to adapt the starting points – see Variable Entry, under Learner-Centered Design), fitted to diverse histories, abilities, and interests.

- Learning Feedback (Differentiated Feedback) – Articulated more as a principle than a strategy of Differentiated Instruction, Learning Feedback points to the importance of tailoring responses to each learner. It is seen as especially important for the development of learner autonomy, based on the assumption that nuanced information on what one has accomplished will afford nuanced insight into what one should do next.

- Self-Differentiated Learning (Self-Differentiation) – a variously defined term that, most often, refers to opportunities provided to individual learners to influence the focus, level, and/or complexity of their learning tasks. The phrase is most often heard in association with Learner-Centered Design, Choice Learning, and/or Personalized Learning. (Note: Not to be confused with Self-Differentiation Theory, under Identity Discourses.)

- Voice and Choice (Meaningful Voice and Choice) – This emphasis in Differentiated Learning is appropriately understood as the simplification and blending of two prominent topics in contemporary educational discourse – namely, empowerment- and identity-focused insights from various Activist Discourses (represented in the trope “voice”) and rights- and efficacy-focused insights from various Personal Agency Discourses (represented in the trope “choice”). A third broad topic is sometimes incorporated by adding the word “meaningful” – which nods toward, but never fully engages, a defining theme of more than a century’s research in Neuro-Focused Discourses, Psyche-Focused Discourses, and Socio-Cultural-Focused Discourses.

- Analogies, Metaphors, and Visual Representations – Apparently anchored in Conceptual Metaphor Theory, this emphasis on using figures of speech and images to engage with ideas at all levels comes in many flavors. Depending on whether the proponent sees these devices as poetic flourish and conceptually foundation, the classroom advice ranges from the banal-but-fun to the challenging-and-powerful.

- Assessment Design – Aligned with Instructional Design Models (contrast: Design Thinking), Assessment Design is that aspect of program planning that attends the sorts of practice tasks and evaluation tools that are useful in monitoring learning progress on an assumed-to-be-linear learning trajectory.

- Backward Planning – This phrase refers to the process of working backward from a predetermined set of learning goals to identify appropriate sub-goals, sequences, learning tasks, and teaching practices. Perhaps the most formal version of Backward Planning is Backward Design.

- Bloom’s Twist – This phrase has emerged as a catch-all for updates to (i.e., rewordings, elaborations, and/or reformattings of) Bloom's Taxonomy, a model of educational learning objectives that identifies and ranks distinct modes of engaging with knowledge.

- Choice Board (Learning Menu) – A Choice Board is an array-based visual device (typically mainly comprised of text, but often incorporating images of various sorts) that is used to help children make informed choices among possible activities, objects, and/or conceptual interpretations.

- Class Rules – One of the few subdiscourses that is specific to Differentiated Instruction, Class Rules arises in the recognition that classrooms in which teaching and learning are differentiated will require more organization, effective routines, and explicit rules. Class Rulesis thus both a reminder and a set of advice to make accommodations to manage and monitor multiple simultaneous activities.

- Classroom Layout and Design – Many discourses on learning offer advice on organizing learning spaces and groups students. In the context of Differentiated Instruction, Classroom Layout and Design tends to focus on matters of grouping students (e.g., according to interest, ability, or topic) and equipping classroom spaces (e.g., with larger tables or mobile workstations rather than stationary desks).

- Concept Attainment – This is a strategy for teaching a concept that foregrounds similarities and differences among instances of that concept. Typically, students are presented with multiple examples and non-examples of the concept and, based on what those instances do or don’t have in common, they are asked to identify features or rules that define it.

- Cubing – This is a strategy for teaching a concept that requires students to examine a concept in different ways. The “cubing” is a reference to use of a 6-faced cube to present different perspectives on on or facets of the concept – typically articulated as questions or tasks for engagement. Students roll to cubes to determine their tasks.

- Curriculum Mapping – This process entails a critical examination of a program of studies, typically aimed at identifying gaps, repetitions, poor sequencing, and other issues. The phrase is most often used to refer to some preparatory activities for curriculum updating and revision initiatives, but it is also used to refer less-grand engagements, such as a critical analysis of a teacher’s unit plan.

- Double-Entry Journal and Essay Writing – These phrases refer to strategies based on a two-column format designed to help learners manage and systematic tasks that involve analysis of multiple elements. It is usually used as a step toward a more conventionally formatted essay or presentation. Users record “raw” information (e.g., quotations or concepts) in one column and to insert commentary (e.g., elaboration, question, critique) for each item in the other column.

- Goal Setting – One of the few subdiscourses that is specific to Differentiated Instruction, Goal Setting arises from the defining principle that different learners will require different goals, and they can be expected to travel different paths to attain those goals. Detailed Goal Setting is thus necessary to ensure that learners have access to appropriate resources as needs arise.

- Graphic Organizers (Knowledge Map; Concept Map; Story Map; Cognitive Organizer; Concept Diagram) – The phrase Graphic Organizer can be used to describe any image-based strategy to represent ideas or knowledge. The most common types include bubble maps, Venn diagrams, and activity flows. Within Differentiated Instruction, Graphic Organizers are most commonly embraced and justified as means to simplify, adapt to ability levels, and engage visual learners.

- Grouping – Within Differentiated Instruction, Grouping refers specifically to clustering students according to their levels of learning. It is justified by the assumption that learning can be linearized – from which it follows that, by breaking down grade-levels into finer-grained intervals, learners can be unproblematically gathered into homogeneous clusters.

- Hot Seat – Adapted from popular usage of the term (referring to assigning full responsibility for something onto someone), the Hot Seatteaching strategy involves assigning students responsibility for specific aspects of a task (e.g., characters in a novel, components of a unit of study, etc.). The underlying assumption is that students will dig deeper into the general matter if they have profound responsibility for an aspect.

- Identity Chart – An Identity Chart is a form of Graphic Organizer (see above) that is focused specifically on the many influences of their individual identities. (It is also frequently applied at community and national levels.)

- Jigsaw – Commonly associated with Cooperative Learning, a Jigsaw is an approach to group-based learning that makes success dependent on interdependence among learners. This is accomplished by breaking and distributing tasks in a manner that compels groups to rely on one another – metaphorically, by each being responsible for one piece of the puzzle.

- Layering (Layered Learning; Layered Curriculum) – A subdiscourse of Differentiated Instruction, Layering shares unquestioned assumptions on learning with Learning Styles Theories and Cognitivism. Layering systematically attends to the simultaneity of academic, physical, social, emotional, and other learnings through processes of deliberate parsing and strategic combining.

- Learning Badges (Educational Badges) – Similar to widespread uses of badges, Learning Badges are physical or digital markers that are intended to serve both as indicators of achievement and devices for extrinsic motivation (see Motivation Theories; contrast Extrinsic Motivation Discourses with Intrinsic Motivation Discourses). Within Differentiated Instruction, they can also serve as important organizing tools for the teacher, who must track the unique progress of each learner.

- Learning Stations Model (Differentiated Stations; Learning Centers; Learning through Workstations; Station Rotation) – The Learning Stations Model involves setting up distinct physical locations, each of which is associated with a specific question or problem that is to be engaged with the resources and/or tools at the station. Students rotate in groups through stations when at prespecified intervals, and station work can be either group- or individual-focused.

- Learning Contracts – Learning Contracts is an extension of Goal Setting (see above) that involves specifying goals and indexing them to time frames in an agreement between the teacher and student (and, often, a parent).

- Learning Model Integration (Integration of Learning Model) – These phrases are interpreted in multiple ways in the educational literature. Most commonly, they are used to describe efforts to blend curriculum elements across subject areas. Less often, they are used to refer to integrating academic and other elements of one’s learning or integrating in-school learnings with out-of-school learnings. They are also sometimes used to refer to a formal discourse that is structured around a blend of principles of “pedagogy” (understood as the study of teaching children) and Andragogy (the study of teaching adults). This integration, it is argued, affords more nuanced and adaptable forms of teaching, as the best directive and the best flexible strategies from both are brought together.

- Learning Stations Model (Differentiated Stations; Learning Centers; Learning through Workstations) – The Learning Stations Model involves setting up distinct physical locations, each of which is associated with a specific question or problem that is to be engaged with the resources and/or tools at the station. Students rotate in groups through stations when at prespecified intervals.

- Literacy Circles (Karen Smith, 1980s) – a strategy for organizing whole-class engagement in reading, principally intended for adolescent-aged learners and aimed at nurturing the attitudes, skills, and strategies associated with good readers. Literacy Circles afford students opportunity to choose a novel from a list generated by the teacher, and they might be characterized as similar to adult book clubs, but with greater structure.

- Open Question (Carol Ann Tomlinson) – questions that permit (and, perhaps, invite) different answers, interpretations, and/or strategies – in the process, affording possibilities for adapting tasks to individual learners

- Parallel Tasks (Carol Ann Tomlinson) – questions about the same concept or topic that are differentiated in ways intended to accommodate to variations in readiness, interests, or profiles among learners

- Place-Based Education (Pedagogy of Place; Community-Based Education; Third Teacher) – This discourse is both an educational philosophy and a pedagogical approach that uses socio-geographical locations (deliberately inclusive of all their cultural, historical, and geophysical aspects) as a “partner” in formal education – that is, as a focus of inquiry, as a source of curriculum, and a dynamic teacher, and as agent in the more-than-human world.

- Reciprocal Teaching – Properly identified as a subdiscourse of Dialogic Learning, Reciprocal Teaching is a reading technique that is conceived as a dialogue between teacher and students in which all participants take turns being the teacher.

- Rubrics – A rubric is a grading guide, typically presented in grid form, one dimension of which is used to identify essential qualities of task work and the other dimension of which indexes work quality to letter grades (or similar). Proponents highlight that expectations are clarified for learners and fairness of grading is more transparent. Distractors counter that Rubrics often press attitudes and efforts toward “make sure to give teachers what they want,” as opposed to, say, “engage authentically with a matter of profound interest.”

- Tiered Learning Targets and Tasks – Specific to Differentiated Instruction, Tiered Learning Targets and Tasks are simply a range of related tasks that vary according to difficulty. With such targets and tasks at hand, the work of differentiating for learners is substantially eased, as the teacher is enabled to assign work based on skill level.

Commentary

While proponents claim that it is informed by brain research, the vocabulary used in the Differentiated Instruction literature to characterize learning, teaching, and education is scattered, inconsistent, and decidedly uncritical. As illustrated by the above list of strategies identified by proponents, the discourse routinely invokes the Acquisition Metaphor, the Attainment Metaphor, Discovery Learning, and Cognitivism – occasionally alongside notions more aligned with Neuroscience and associated Embodiment Discourses, despite the fact that many of these discourses are highly critical of one another and often conceptually incompatible. Thus, while Differentiated Instruction might sound like the opposite of one-size-fits-all Instructivism, it is actually grounded in exactly the same sensibilities about learning. Additionally, and perhaps most condemningly, given the broad popularity of the discourse, Differentiated Instruction lacks empirical grounding.Authors and/or Prominent Influences

Carol Ann TomlinsonStatus as a Theory of Learning

Differentiated Instruction is not a theory of learning.Status as a Theory of Teaching

Differentiated Instruction is a theory of teaching. Its core advice revolves around pre-assessments (to gauge interests, attitudes, and established understandings) and ongoing formative assessments (to adjust and refocus content and instructional strategies, as necessary), all aimed at formatting challenging-but-not-frustrating activities for the learner.Status as a Scientific Theory

Differentiated Instruction has been accused of entirely lacking a robust research base. Critics regularly charge that research into modifying classroom approaches to cater to learning styles simply does not generate statistically significant improvements. Concisely, Differentiated Instruction fails to meet any of our criteria of a scientific theory.Subdiscourses:

- Analogies, Metaphors, and Visual Representations

- Assessment Design

- Backward Planning

- Bloom’s Twist

- Choice Board (Learning Menu)

- Class Rules

- Classroom Layout and Design

- Concept Attainment

- Cubing

- Curriculum Mapping

- Differentiated Assessments

- Differentiated Teaching

- Double-Entry Journal and Essay Writing

- Goal Setting

- Graphic Organizers (Knowledge Map; Concept Map; Story Map; Cognitive Organizer; Concept Diagram)

- Grouping

- Hot Seat

- Identity Chart

- Jigsaw

- Layering (Layered Learning; Layered Curriculum)

- Learning Badges (Educational Badges)

- Learning Centers (Center-Based Learning)

- Learning Contracts

- Learning Feedback (Differentiated Feedback)

- Learning Model Integration (Integration of Learning Model)

- Learning Stations Model (Differentiated Stations; Learning Centers; Learning through Workstations; Station Rotation)

- Literacy Circles

- Open Question

- Parallel Tasks

- Place-Based Education (Pedagogy of Place; Community-Based Education; Place-Conscious Education)

- Reciprocal Teaching

- Rubrics

- Self-Differentiated Learning (Self-Differentiation)

- Tiered Learning Targets and Tasks

- Voice and Choice (Meaningful Voice and Choice)

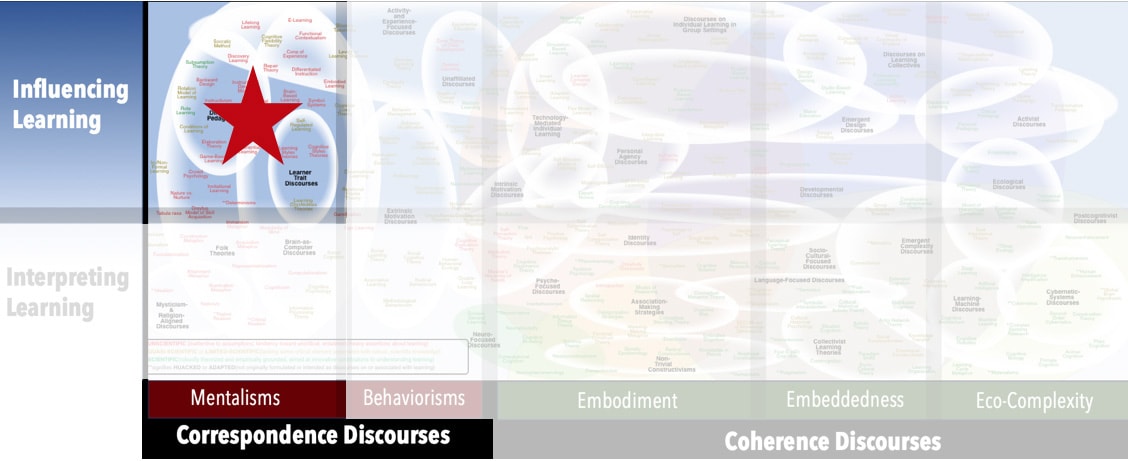

Map Location

Please cite this article as:

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2023). “Differentiated Instruction” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com.

⇦ Back to Map

⇦ Back to List